By Ken Barrett

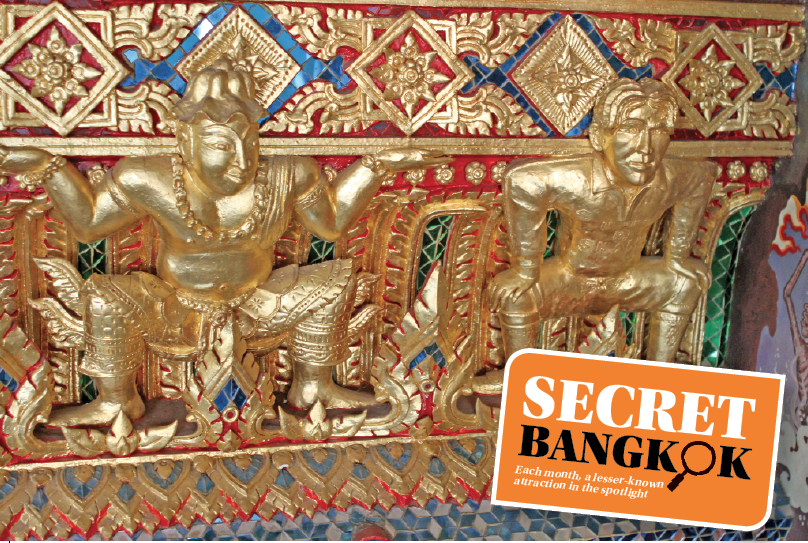

| TEMPLE of the Dawn. Tick! Temple of the Emerald Buddha. Tick! Marble Temple. Tick! Temple of the Golden Buddha. Tick! Right, that’s the Bangkok temples done. What’s next? Over many years of tramping Bangkok’s streets seeking out architectural oddities I have discovered numerous temples that have curious stories attached to them. These are seldom mentioned in the guidebooks, and it is not always easy to winkle out the information, but finding them is immensely satisfying. Why does an embossed image of footballer David Beckham appear on the base of the Buddha image at Wat Pariwat, on Rama III Road? (The abbot likes football.) Why do cartoon figures of Western policemen guard the entrance to Wat Ratchabophit, on Atsadang Road? (The temple was designed to symbolise the growing relationship between Thailand and Europe.) |

Why was a chapel built in the form of a Chinese junk at Wat Yannawa, on Charoen Krung Road?

In the earliest years of Bangkok, with almost no contact with the West, Thailand’s trade was almost exclusively with China. King Rama III, who reigned from 1824 to 1851, knew that changes were inevitable, with the European nations now using powerful steamships and exerting greater influence throughout the region. The king wanted future generations to be aware of the importance that the China trade once had, and so he built a stone replica of a Chinese cargo vessel, a yannawa, in the grounds of an old temple that stood at the entrance to the harbour.

Wat Yannawa is sometimes mentioned in guidebooks, but across the river in Thonburi is a curious although unconnected echo of the junk chapel. Follow the lane that passes beside Taksin Hospital and the way leads between old timbered houses to a small canal, on the bank of which is Wat Thong Noppakhun, a temple of unknown age. In the compound is a Chinese sailing ship, built of concrete, smaller than the one at Wat Yannawa, and of a much later date.

Painted cream and red, and with a bodhi tree as a mast, the vessel is a shrine and carries an inscription in Thai that commemorates the arrival of Buddhist monks from China and Japan. Behind the vessel, at the concrete rudder, is a small grave carrying an inscription in Chinese stating that it symbolises “a grave of tens of thousands of people,” and that it was placed there on the day of the Ching Ming festival in the 23rd year of the National Republic of China. This was 1934.

Beyond this, the shrine is silent as to its purpose, although it seems most likely it honours the dead from the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, which began in 1931.

Another oddity with no immediate explanation can be found at Wat Mon, on the bank of Klong Bangkok Yai. Built by a community of Mon in the latter stages of the Ayutthaya era, the temple was enlarged and renovated by one of the heroes of the Thonburi period, Phraya Pichai.

Known to history as Dap Hak, or ‘Broken Sword,’ from a ferocious battle he had fought even though his blade had broken, Pichai wanted to atone for the killing by restoring the old temple. There is a chapel near the gate, and inside is a figure of the Buddha lying flat upon its back, wrapped in a gold sheet. The position symbolises the time immediately before cremation, but is rare in Buddhist iconography. It is believed to be the only such image of its kind in Thailand, and no one knows why Pichai selected this form.

Walk northwards through Thonburi, to the green steel framework of the Memorial Bridge, and beside the approach road is a rather splendid iron fence painted in fire engine red, surrounding the compound of Wat Prayoon. Take a closer look, and the fence is fashioned in the shape of lances and arrows, its arched sections bristling with axes and swords.

In the earliest years of Bangkok, with almost no contact with the West, Thailand’s trade was almost exclusively with China. King Rama III, who reigned from 1824 to 1851, knew that changes were inevitable, with the European nations now using powerful steamships and exerting greater influence throughout the region. The king wanted future generations to be aware of the importance that the China trade once had, and so he built a stone replica of a Chinese cargo vessel, a yannawa, in the grounds of an old temple that stood at the entrance to the harbour.

Wat Yannawa is sometimes mentioned in guidebooks, but across the river in Thonburi is a curious although unconnected echo of the junk chapel. Follow the lane that passes beside Taksin Hospital and the way leads between old timbered houses to a small canal, on the bank of which is Wat Thong Noppakhun, a temple of unknown age. In the compound is a Chinese sailing ship, built of concrete, smaller than the one at Wat Yannawa, and of a much later date.

Painted cream and red, and with a bodhi tree as a mast, the vessel is a shrine and carries an inscription in Thai that commemorates the arrival of Buddhist monks from China and Japan. Behind the vessel, at the concrete rudder, is a small grave carrying an inscription in Chinese stating that it symbolises “a grave of tens of thousands of people,” and that it was placed there on the day of the Ching Ming festival in the 23rd year of the National Republic of China. This was 1934.

Beyond this, the shrine is silent as to its purpose, although it seems most likely it honours the dead from the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, which began in 1931.

Another oddity with no immediate explanation can be found at Wat Mon, on the bank of Klong Bangkok Yai. Built by a community of Mon in the latter stages of the Ayutthaya era, the temple was enlarged and renovated by one of the heroes of the Thonburi period, Phraya Pichai.

Known to history as Dap Hak, or ‘Broken Sword,’ from a ferocious battle he had fought even though his blade had broken, Pichai wanted to atone for the killing by restoring the old temple. There is a chapel near the gate, and inside is a figure of the Buddha lying flat upon its back, wrapped in a gold sheet. The position symbolises the time immediately before cremation, but is rare in Buddhist iconography. It is believed to be the only such image of its kind in Thailand, and no one knows why Pichai selected this form.

Walk northwards through Thonburi, to the green steel framework of the Memorial Bridge, and beside the approach road is a rather splendid iron fence painted in fire engine red, surrounding the compound of Wat Prayoon. Take a closer look, and the fence is fashioned in the shape of lances and arrows, its arched sections bristling with axes and swords.

| The fence was ordered from Britain in the time of Rama III, and it was originally intended for an area of the Royal Palace. When it arrived, however, the king decided he didn’t want it. That left the treasury minister, Dit Bunnag, with an awful lot of fence. Bunnag was building a temple of his own, and that explains how Wat Prayoon ended up having such a distinctly unBuddhist fence. Locals were quick to dub the temple Wat Rua Lek, or Iron Fence Temple. Chinatown is an area rich in curious temples and shrines. Sampeng Lane runs through this district, and was the first thoroughfare to be built when Chinatown was founded. At the eastern end of the lane is the temple from which the thoroughfare derives its name, Wat Sampeng. Fierce Chinese guards are painted on the doors to the compound, and there are Chinese figures inside. Behind the chapel is a flat black stone engraved with auspicious symbols. Kroma Luang Rak Ronnaret was a prince, the fifteenth son of Rama I. He became close friends with the man who was to become Rama III, and when the king ascended the throne Rak Ronnaret was himself given great powers. These powers he abused with dangerous enthusiasm. He became a grave liability, and as he was too powerful to be dismissed, he was arrested and accused of threatening to dethrone the king. There could be only one end to the affair. On the morning of December 12, 1848, the prince was taken to Wat Sampeng, a velvet sack was placed over his head, his head was placed upon the black execution stone, and he was beaten to death with a sandalwood club. The Singapore Free Press & Mercantile Advertiser, which carried a lengthy account of the prince’s downfall, reported that his body was thrown into the river. The Rebel’s Execution Stone, as the block is known, seems to be treated with little respect: the last time I was there, the enclosure was acting as a repository for builders’ rubble. |

| Sampeng Lane was Bangkok’s first red-light district, although the brothels were identifiable by a green light above the door. These were legal establishments, and vied with each other in the quality of their décor and the sophistication of their girls. The brothel owners prospered, and one, a Mrs Faeng, built a temple from her earnings. Named Wat Kanikapon, it can be found on Phlap Phla Chai Road, in the northern part of Chinatown. In homage to its origins, roses decorate the entrance arch, the detailing around the window frames evokes the image of green curtains, and a wooden curtain is drawn aside at the front door. A bust of Mrs Faeng can be found in a niche behind the temple, although it’s not a very good one and looks like it has been made from a mould used for monk images, to the extent that the poor lady has to have a wig to hide her bald head. One of the most intriguing temple tales relates to Wat Ratchaburana, which is at the foot of the Memorial Bridge, and which is also known as Wat Liab, after the Chinese merchant who built it. A distinctive prang dating from the Rama III era stands at the entrance but inside the compound is a structure even more curious; a three-storey Japanese temple, its design based on the Temple of the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto. The temple is actually an ossuary, built in 1935 to house the ashes of Japanese citizens, and a Japanese monk is in permanent residence. Bangkok’s main electricity generating station stood next to Wat Liab, and in the latter stages of World War II, with the Japanese army still occupying Thailand, it became a prime target for allied bombers. In April 1945 the temple itself was hit by a stray bomb and so badly damaged that it was deleted from the official list. Only the prang and, ironically, the Japanese ossuary survived. In June of that year, one of the most notorious Japanese military commanders, Colonel Tsuji Masanobu, arrived in Bangkok to help quell a likely uprising of the Thai army. When Emperor Hirohito surrendered on August 15, Tsuji found himself stranded. With war crimes to his credit that included participation in a massacre of Chinese in Singapore, organising the Bataan Death March in the Philippines, and roasting and eating the liver of an executed American airman, Tsuji rightly concluded he would be of interest to the invading Allied forces. Tsuji removed his uniform and went to the bombed-out ruins of Wat Liab, where he was granted sanctuary. Disguising himself as a Buddhist monk, he hid in the ossuary until late October, when the Allied forces began to close in on him. On October 29, Tsuji had a rendezvous with members of Chiang Kai Shek’s Blue Shirt Society, who were operating out of an office on Surawong Road. A deal was done. Two days later, now disguised as a Chinese merchant and accompanied by two escorts, he boarded a train at Hua Lampong and made his way to Ubon. From there he crossed the Mekong in a canoe, and via Vientiane and Hanoi he made his way to Chungking. Tsuji finally arrived in Japan in 1948, where perhaps most curious of all he somehow managed to evade war crimes charges. Instead of being hanged, he became a politician. Ken Barrett is the author of 22 Walks in Bangkok: Exploring the City’s Back Lanes and Byways. |