by Greg BeattyIn a long and event-filled career spanning electric blues to the psychedelic era, Matthew Kelly has played with some music’s legendary figures, including B.B. King, Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, Albert Collins, Bobby Bland, Luther Tucker and Mel Brown and more. But his biggest claim to fame was performing with the Grateful Dead, one of the most respected rock bands of all time. Now happily settled in Pattaya, Matthew can still be persuaded to turn out for the occasional gig, as he did recently at the Royal Varuna Yacht Club |

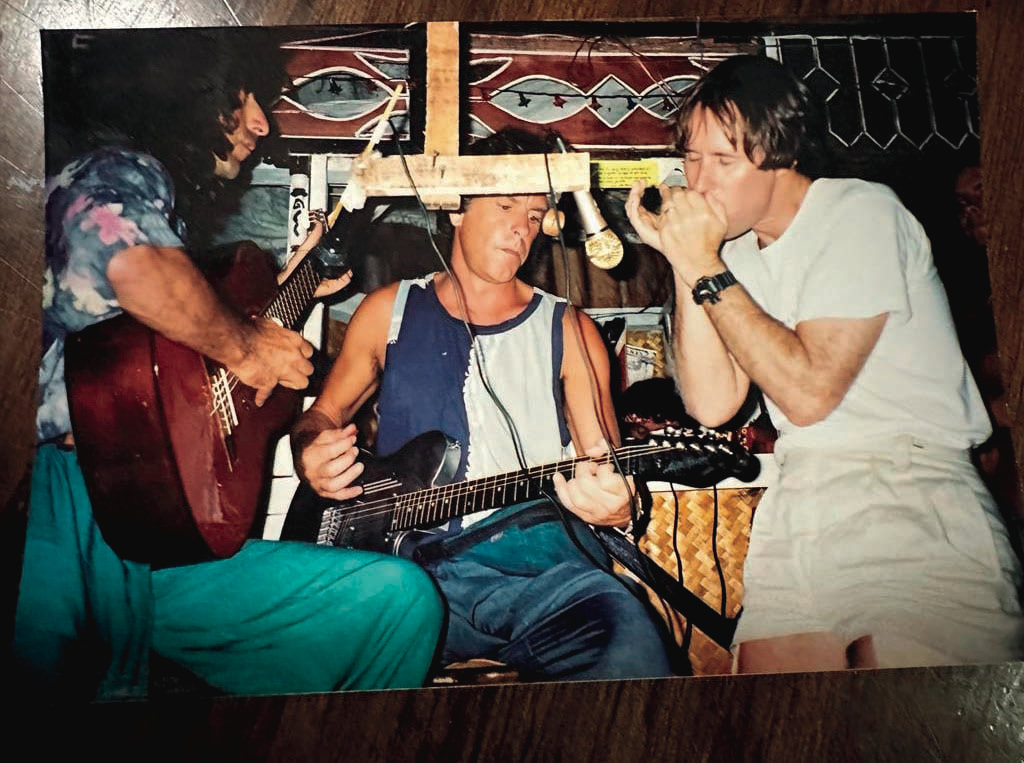

The Royal Varuna Yacht Club, Thailand’s premier sailing venue located two hours’ drive south of Bangkok, seemed the most unlikely place to find Matthew Kelly.

Decades ago Kelly played blues harp on three Grateful Dead albums and in several of the group’s New Year Eve concerts. Before that he was the only white guy in otherwise all-black bands,

Decades ago Kelly played blues harp on three Grateful Dead albums and in several of the group’s New Year Eve concerts. Before that he was the only white guy in otherwise all-black bands,

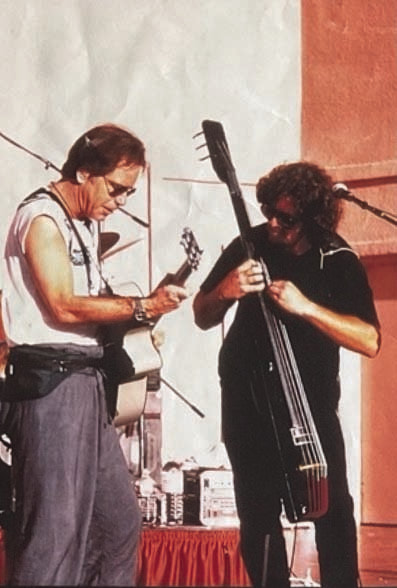

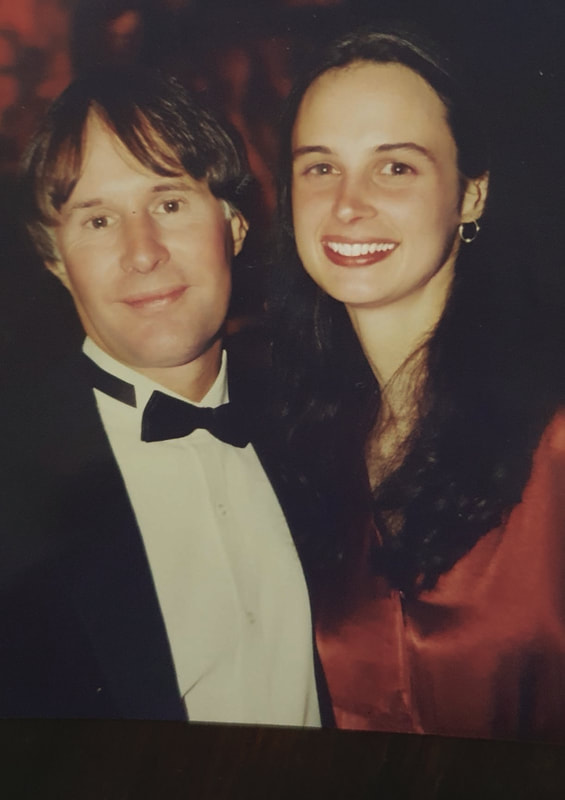

Bob Weir, Rob Wasserman, and Matt Kelly

| People talk of their lives in metaphors – journeys, roads taken, or to use a Grateful Dead metaphor, strange trips. In Kelly’s case, odyssey is most apt. traveling the dusky roads of the Chitlin Circuit. Club owners sold chitlins and other soul food from their kitchens. Whisky was sold by the bottle, not by the glass, and the bouncers weighed 300 pounds and carried two pistols. People talk of their lives in metaphors – journeys, roads taken, or to use a Grateful Dead metaphor, strange trips. In Kelly’s case, odyssey is most apt. An odyssey is distinct from other journeys. An odyssey doesn’t have an end; there’s no going back to the beginning. It’s an extended intellectual or spiritual quest marked by whirly changes of fortune and devils at the crossroad. |

Devils in the House

With every new fork in the road, you take it, and keep going onward. There was the night Kelly performed at a house party hosted by Sonny Barger, outlaw biker and founding member of the Oakland, California chapter of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Kelly and his band were scheduled to play from 8 p.m. to midnight, followed by the Doobie Brothers. When the Doobie Brothers arrived, the bikers, more than one hundred of them, were snorting white meth powder off of daggers. The Doobies Scooby-dooby doo-ed out the door without time for apologies.

Kelly and his band took the stage for another set. “When we finished,” says Kelly, “they brandished their fists like mallets demanding us to snort off their daggers and play on. I was terrified for my life. They made us play until 9 a.m. We had to recycle songs endlessly making up gibberish lyrics on the spot.”

Later there were tours fronting for Aerosmith, the Eagles, Eric Clapton, ELO, and Ritchie Blackmore. It’s easy to go down rabbit holes while Kelly reminisces. Back to the Here and Now.

With every new fork in the road, you take it, and keep going onward. There was the night Kelly performed at a house party hosted by Sonny Barger, outlaw biker and founding member of the Oakland, California chapter of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Kelly and his band were scheduled to play from 8 p.m. to midnight, followed by the Doobie Brothers. When the Doobie Brothers arrived, the bikers, more than one hundred of them, were snorting white meth powder off of daggers. The Doobies Scooby-dooby doo-ed out the door without time for apologies.

Kelly and his band took the stage for another set. “When we finished,” says Kelly, “they brandished their fists like mallets demanding us to snort off their daggers and play on. I was terrified for my life. They made us play until 9 a.m. We had to recycle songs endlessly making up gibberish lyrics on the spot.”

Later there were tours fronting for Aerosmith, the Eagles, Eric Clapton, ELO, and Ritchie Blackmore. It’s easy to go down rabbit holes while Kelly reminisces. Back to the Here and Now.

| Tales from Varuna A cool breeze blows in from the Gulf of Thailand on this New Year’s Eve. Kelly sits behind a percussion kit with Bobby Parrs on guitar to usher in 2023. The duo plays easygoing cover songs with a jazzy fusion in front of 50 or so sailing families, nary a few who could name one Grateful Dead song or know the difference between a chitlin and a chicklet. Kelly gushes with tales between sets. He regales with stories through several epochs of American culture. His life is a highlight reel of daring do. |

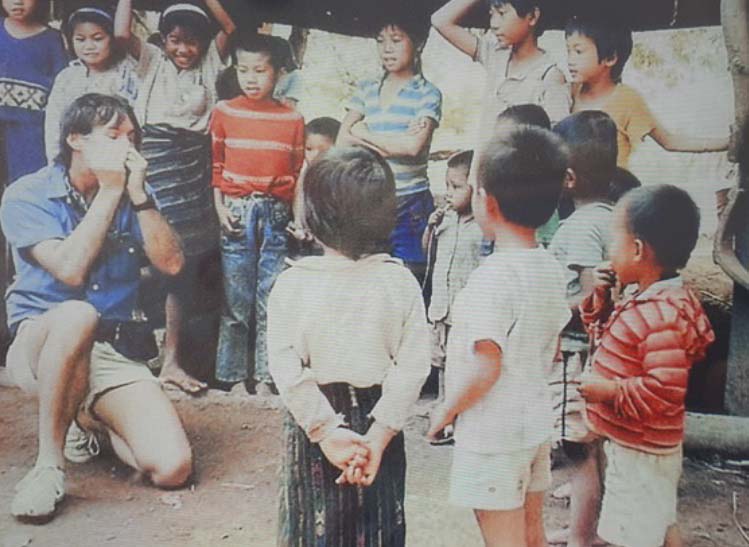

| Kelly, and his wife Mary have resided here for more than twenty years. They founded the Amicus Foundation of Thailand, a non-profit organization that provides educational opportunities for children and works with impoverished communities. Kelly plays small gigs occasionally, such this New Year’s Eve, and he’s working on an album that combines new songs with songs from his vault. Trouble at the Border Life starts over again and again for Kelly. Opportunity arises, he says yes, and sets sail. Reflecting on a low point from his youth, he faced a five-year prison sentence. “A friend and I were caught with a gunny sack of ganja at the Mexico-US border,” he says. “Marijuana is legal in California now, but back then it was a criminal offence. I was a good-looking lad. There’s no way I would have survived prison culture.” |

Kelly’s father, a media magnet in the late 1960s and referred to as “the most charming businessman in San Francisco” pulled the ultimate string – a lifeline telephone call to the Governor. The boys were given two-years’ probation. and later President Lyndon B. Johnson issued a full Presidential pardon. The defendant appearing in the case immediately before them, with a lesser quantity, received a seven-year prison sentence.

Ironically, and with no connection to that border episode (but with a connection to Kelly’s friendship with Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater’s niece), Kelly’s biggest high was a treatment prescribed by John F. Kennedy’s doctor, the scandalous Max Jacobson, known as the original Dr. Feelgood. “He gave me a slurry of goodies to fix recurring headaches from an old rugby injury,” says Kelly. “The doctor said they’ll make me feel better than a wanting woman in satin sheets. He was right. I was spaced out for three days.”

There’s a Beatle in my Club

Kelly’s most honorable recognition was the Genesis Award for a song he co-wrote to raise environmental awareness in support of Julia Butterfly Hill, the woman who lived for two years in a 180-foot-tall, 1500-year-old California Redwood tree. Michael Jackson, Peter Gabriel, and Paul McCartney won the same award in other years.

Like a yo-yo, Kelly’s odyssey spins up and down from fortune to foible and back again. If there’s a pattern, it’s that he’s a magnet for very talented or troubled souls. Nearly everyone he’s met has a Wikipedia page.

Kelly’s partner in crime at the Mexico border was his childhood friend, Tim Hovey, a gap-toothed kid with big ears. Despite Hovey’s cranial features, or precisely because of them, he became a child actor. His debut was in a TV episode of Lassie. He went on to appear in movies starring

Ironically, and with no connection to that border episode (but with a connection to Kelly’s friendship with Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater’s niece), Kelly’s biggest high was a treatment prescribed by John F. Kennedy’s doctor, the scandalous Max Jacobson, known as the original Dr. Feelgood. “He gave me a slurry of goodies to fix recurring headaches from an old rugby injury,” says Kelly. “The doctor said they’ll make me feel better than a wanting woman in satin sheets. He was right. I was spaced out for three days.”

There’s a Beatle in my Club

Kelly’s most honorable recognition was the Genesis Award for a song he co-wrote to raise environmental awareness in support of Julia Butterfly Hill, the woman who lived for two years in a 180-foot-tall, 1500-year-old California Redwood tree. Michael Jackson, Peter Gabriel, and Paul McCartney won the same award in other years.

Like a yo-yo, Kelly’s odyssey spins up and down from fortune to foible and back again. If there’s a pattern, it’s that he’s a magnet for very talented or troubled souls. Nearly everyone he’s met has a Wikipedia page.

Kelly’s partner in crime at the Mexico border was his childhood friend, Tim Hovey, a gap-toothed kid with big ears. Despite Hovey’s cranial features, or precisely because of them, he became a child actor. His debut was in a TV episode of Lassie. He went on to appear in movies starring

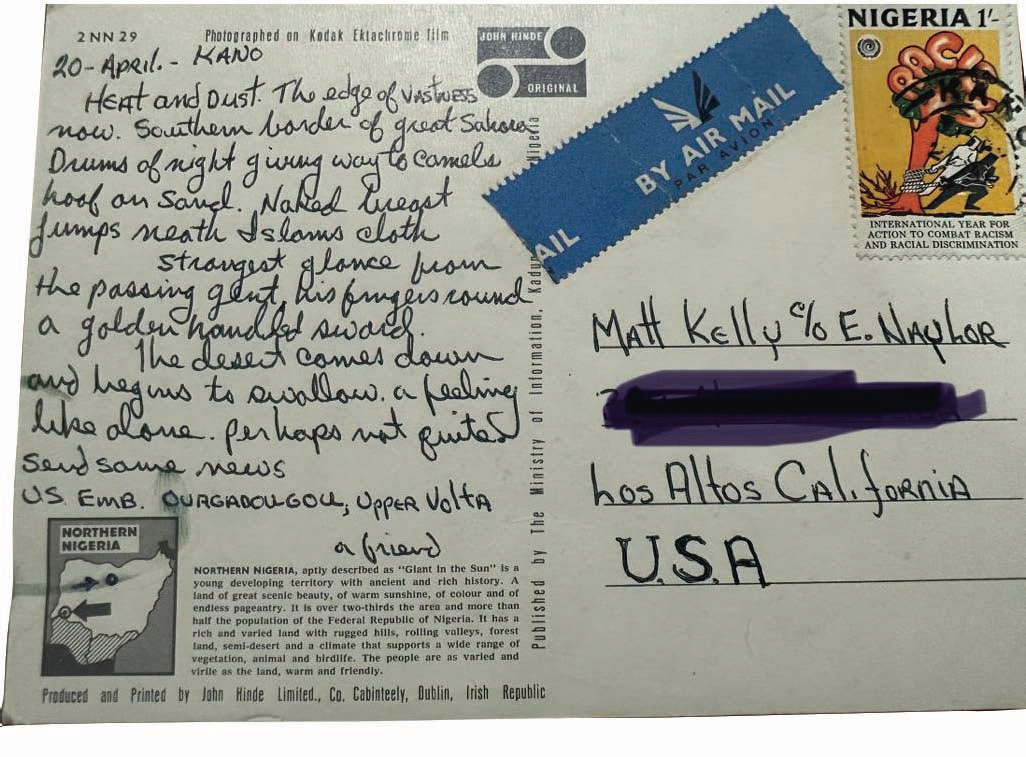

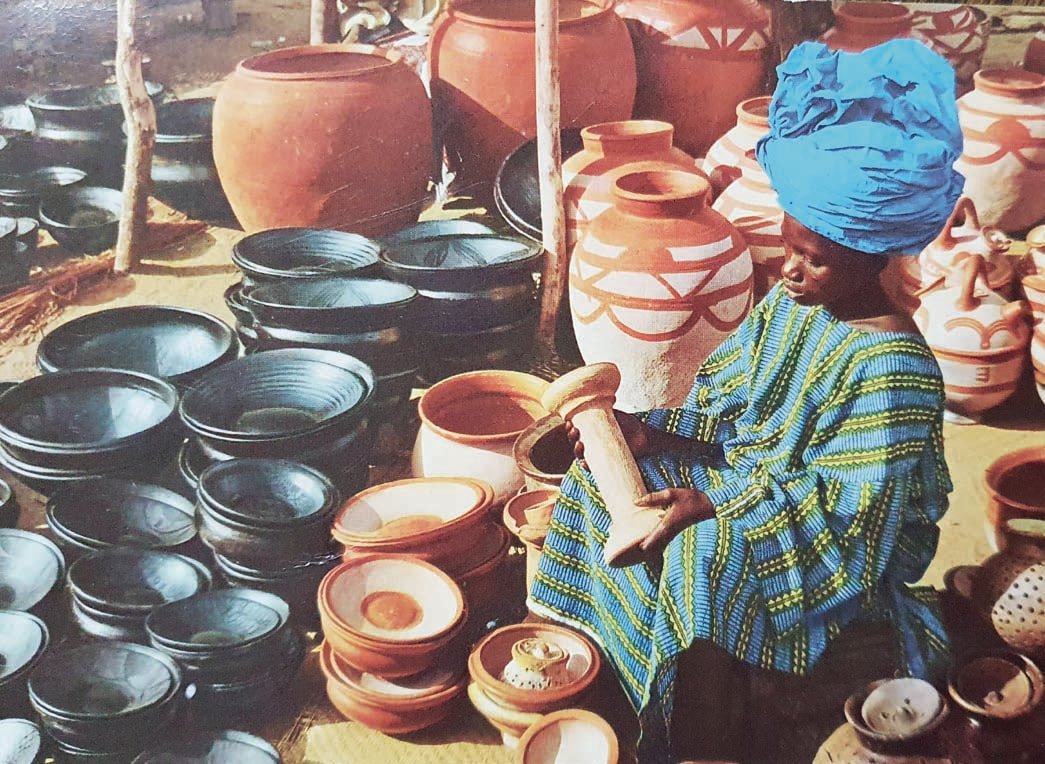

| The boy’s family happened to be a household of musicians, The Soul Majestics. “I can play guitar and harp,” Kelly told them. They treated him like family. “They invited me to play along in the clubs Charlton Heston and Lauren Bacall. Upon retirement from acting, Hovey became a road manager for Kingfish, a band that included members of the Grateful Dead. Post Cards from Ouagadougou Kelly still treasures a postcard he received from Hovey, postmarked from Upper Volta. “Tim traveled across sub-Sahara Africa and went to Ouagadougou, just because he liked the name.” Hovey’s wiki page says he committed suicide in 1989. Kelly believes the cause of death was accidental. |

Back in 1969, Kelly’s yo-yo was spinning up. He labored on the docks of New Orleans, where crude oil tankers came to port. On one occasion, a young black boy slipped on an oil slick and fell down a well. Dock workers ignored the boy as he lay unconscious. “The well was full of toxic sludge,” says Kelly. “He was going to die. I climbed down, lifted him out, and carried him home.”

The boy’s family happened to be a household of musicians, The Soul Majestics. “I can play guitar and harp,” Kelly told them. They treated him like family. “They invited me to play along in the clubs. Kelly resigned from the dock works. He set out to play with blues musicians that influenced the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and other emerging bands from the UK.

The Soul Majestics, with Kelly on harp, hoboed their way through the coal mining towns of Indiana and Kentucky and the brackish Bayou of Louisiana. Kelly was familiar with the Chitlin Circuit, having previously toured with other blues musicians. When Sly Stone’s mother heard Kelly play harp, she said, “I feel like I’m in church with the holy spirit.”

In the years that followed, Kelly played with B.B. King, Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, Albert Collins, Bobby Bland, Luther Tucker, Mel Brown and more. Brown became a mentor to the young Kelly and took him to play at gigs in pubs frequented by Ray Charles in Watts, Los Angeles.

It was in Watts that Brown introduced Kelly to T-Bone Walker, the guitarist who taught Steve Miller to play the guitar behind his back and with his teeth. Jimi Hendrix admired Walker and would later imitate Walker’s showman tricks. Kelly became a member of Walker’s band. At one concert, Walker had a stroke in the middle of a guitar solo. Kelly rushed to his side and caught him.

The boy’s family happened to be a household of musicians, The Soul Majestics. “I can play guitar and harp,” Kelly told them. They treated him like family. “They invited me to play along in the clubs. Kelly resigned from the dock works. He set out to play with blues musicians that influenced the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and other emerging bands from the UK.

The Soul Majestics, with Kelly on harp, hoboed their way through the coal mining towns of Indiana and Kentucky and the brackish Bayou of Louisiana. Kelly was familiar with the Chitlin Circuit, having previously toured with other blues musicians. When Sly Stone’s mother heard Kelly play harp, she said, “I feel like I’m in church with the holy spirit.”

In the years that followed, Kelly played with B.B. King, Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, Albert Collins, Bobby Bland, Luther Tucker, Mel Brown and more. Brown became a mentor to the young Kelly and took him to play at gigs in pubs frequented by Ray Charles in Watts, Los Angeles.

It was in Watts that Brown introduced Kelly to T-Bone Walker, the guitarist who taught Steve Miller to play the guitar behind his back and with his teeth. Jimi Hendrix admired Walker and would later imitate Walker’s showman tricks. Kelly became a member of Walker’s band. At one concert, Walker had a stroke in the middle of a guitar solo. Kelly rushed to his side and caught him.

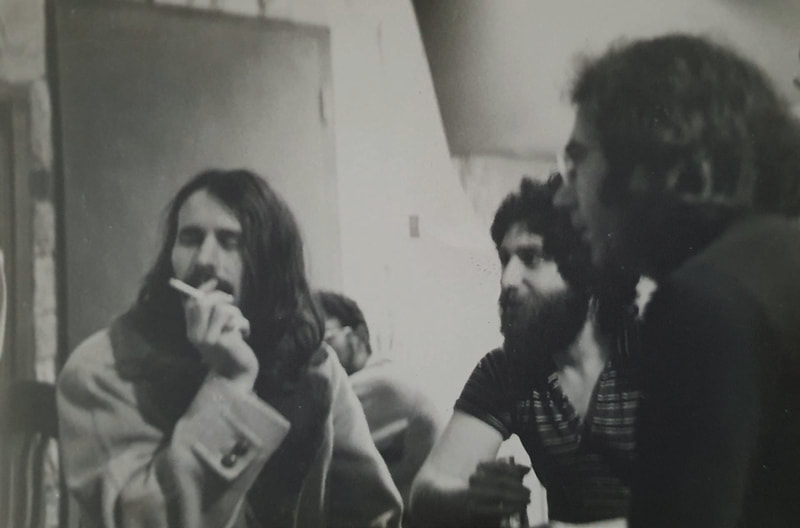

| Champion Jack Dupree and Me Kelly also toured in England with Champion Jack Dupree, a blues pianist from New Orleans who sipped whiskey between songs and told bawdy jokes. Kelly played blues harp to Dupree’s boogie-woogie piano. The two musicians toured for six months in Dupree’s dented station wagon-cum-Mardi-Gras caravan with dangling dashboard beads and fuzzy dice. Orphaned at eight, Dupree learned to play the piano at an institution for delinquent boys. (Six years earlier, Louis Armstrong was sent to the same Home.) During that time, Dupree met one of the greatest boxers of all time, Joe Louis, who encouraged him to box. Dupree excelled at piano and boxing. He won Golden Gloves and later influenced Fats Domino. In England, black musicians were treated more respectfully. Back in Louisiana, Dupree’s boxing skills were not just for sport. The Ku Klux Klan was a prominent and ugly legacy of the antebellum South. Kelly was guilty by association. “I know the taste of metal,” says Kelly. “One member put a 357 magnum in my mouth and asked, ‘Do you want to know the taste of lead too.’” |

Who Let the Dogs In?

In addition to Hovey, Bob Weir is another boyhood friend that features in Kelly’s odyssey. They grew up in the same neighborhood. Weir became Kelly’s gateway to the Grateful Dead. Kelly played on Wake of the Flood, Shakedown Street, and The Closing of Winterland. Kelly also sang and produced his own songs, some of which were accompanied by Weir, Jerry Garcia, and Brent Mydland. Weir and Kelly played together in three other groups - Kingfish, Bobby and the Midnites, and Ratdog. Ratdog played at President Clinton’s 1997 Inauguration Ball.

Grateful Dead stories have been well covered in documentaries, biographies, and autobiographies. But what did it feel like to be standing foot-to-foot on stage with those guys?

Ungrateful Kick

“It was an honor,” says Kelly. But the experience was not always great. After one concert, Billy Kreutzmann, drummer, kicked Kelly so hard in the groin that he’s sterile. (“But not impotent,” Kelly adds.) Kelly filed a lawsuit, and later said he wished he’d dropped it.

Kelly saw Jerry Garcia at his best and worst. “After he came out of the hospital from his diabetic coma, he looked good,” says Kelly. “He started scuba diving and eating properly. Before that, he was sort of anti-health, eating a lot of junk food.”

Kelly continues, “I’ll never forget how he’d hibernate in Rock Skully’s prison-like basement attending to his heroin addiction. His pallor was, ghostly.” (Skully was a manager for the Grateful Dead and Kingfish. He was fired in 1984 after unsuccessfully battling his own drug addiction. Skully’s son, Luke, died in the tsunami in Thailand in 2004.)

In addition to Hovey, Bob Weir is another boyhood friend that features in Kelly’s odyssey. They grew up in the same neighborhood. Weir became Kelly’s gateway to the Grateful Dead. Kelly played on Wake of the Flood, Shakedown Street, and The Closing of Winterland. Kelly also sang and produced his own songs, some of which were accompanied by Weir, Jerry Garcia, and Brent Mydland. Weir and Kelly played together in three other groups - Kingfish, Bobby and the Midnites, and Ratdog. Ratdog played at President Clinton’s 1997 Inauguration Ball.

Grateful Dead stories have been well covered in documentaries, biographies, and autobiographies. But what did it feel like to be standing foot-to-foot on stage with those guys?

Ungrateful Kick

“It was an honor,” says Kelly. But the experience was not always great. After one concert, Billy Kreutzmann, drummer, kicked Kelly so hard in the groin that he’s sterile. (“But not impotent,” Kelly adds.) Kelly filed a lawsuit, and later said he wished he’d dropped it.

Kelly saw Jerry Garcia at his best and worst. “After he came out of the hospital from his diabetic coma, he looked good,” says Kelly. “He started scuba diving and eating properly. Before that, he was sort of anti-health, eating a lot of junk food.”

Kelly continues, “I’ll never forget how he’d hibernate in Rock Skully’s prison-like basement attending to his heroin addiction. His pallor was, ghostly.” (Skully was a manager for the Grateful Dead and Kingfish. He was fired in 1984 after unsuccessfully battling his own drug addiction. Skully’s son, Luke, died in the tsunami in Thailand in 2004.)

Mythical Legend

Garcia went from living a hand-to-mouth bohemian existence at the beginning to propelling the band to earn $285 million during their tours in the 1990’s. He became the iconic figure of the counterculture before he died at the age of 53, in 1995. He had a heart attack in a drug-treatment facility.

“Garcia never looked like a legend,” says Kelly. “If looks were a game of poker, you wouldn’t bet on him. But he could light up a room. He could captivate a stadium.” Kelly pauses, then bows his head. “People make their own decisions. Have some of this became I need that. Carefree consumption became compulsive consumption. The addictions take over.”

Amicus Foundation of Thailand

Kelly’s music career spans from the electric blues to the psychedelic era of music. One is rooted in facing hard realities head on, the injustice of humanity. The other sought to escape them, to explore new universes of the mind. “My fork in the road was always a choice between reinforcing what I was already doing or finding out who am I going to be in my next Terrapin Station,” says Kelly. “I’ve always wanted to be facing forward. Terrapin Station stands as a ‘place’ in imagination, full of potential.”

All directions forward now are in Thailand. Kelly, and his wife Mary, have resided here for more than twenty years. They founded the Amicus Foundation of Thailand, a non-profit organization that provides educational opportunities for children and works with impoverished communities. Kelly plays small gigs occasionally, such this New Year’s Eve, and he’s working on an album that combines new songs with songs from his vault.

Karma?

Perhaps there are lessons from Kelly’s odyssey. With all the greats whom Kelly met, it wasn’t their story he lived. He wrote his own story, his odyssey. “What you stand for is represented by who you are, and it’s not an issue of associations,” says Kelly.

Perhaps it’s to understand that our journeys or odysseys are marked by scattershot moments that seem inconsequential at the time but become pivotal. Did karma reward Kelly for his tender deed to save the boy in the well? Did Lydon B. Johnson’s pardon cosmically guide all subsequent events to unfold?

For certain, happenstance doesn’t mean we let things come to us. How we narrate our own story is a matter of attitude. When we fetch the boy in the well, karma or no karma, we choose our own narration.

Greg Beatty is a freelance storyteller contactable at gregfieldbeatty@gmail.com

Garcia went from living a hand-to-mouth bohemian existence at the beginning to propelling the band to earn $285 million during their tours in the 1990’s. He became the iconic figure of the counterculture before he died at the age of 53, in 1995. He had a heart attack in a drug-treatment facility.

“Garcia never looked like a legend,” says Kelly. “If looks were a game of poker, you wouldn’t bet on him. But he could light up a room. He could captivate a stadium.” Kelly pauses, then bows his head. “People make their own decisions. Have some of this became I need that. Carefree consumption became compulsive consumption. The addictions take over.”

Amicus Foundation of Thailand

Kelly’s music career spans from the electric blues to the psychedelic era of music. One is rooted in facing hard realities head on, the injustice of humanity. The other sought to escape them, to explore new universes of the mind. “My fork in the road was always a choice between reinforcing what I was already doing or finding out who am I going to be in my next Terrapin Station,” says Kelly. “I’ve always wanted to be facing forward. Terrapin Station stands as a ‘place’ in imagination, full of potential.”

All directions forward now are in Thailand. Kelly, and his wife Mary, have resided here for more than twenty years. They founded the Amicus Foundation of Thailand, a non-profit organization that provides educational opportunities for children and works with impoverished communities. Kelly plays small gigs occasionally, such this New Year’s Eve, and he’s working on an album that combines new songs with songs from his vault.

Karma?

Perhaps there are lessons from Kelly’s odyssey. With all the greats whom Kelly met, it wasn’t their story he lived. He wrote his own story, his odyssey. “What you stand for is represented by who you are, and it’s not an issue of associations,” says Kelly.

Perhaps it’s to understand that our journeys or odysseys are marked by scattershot moments that seem inconsequential at the time but become pivotal. Did karma reward Kelly for his tender deed to save the boy in the well? Did Lydon B. Johnson’s pardon cosmically guide all subsequent events to unfold?

For certain, happenstance doesn’t mean we let things come to us. How we narrate our own story is a matter of attitude. When we fetch the boy in the well, karma or no karma, we choose our own narration.

Greg Beatty is a freelance storyteller contactable at gregfieldbeatty@gmail.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed