Long-term expat, author and restaurateur Harlan Wolff reflects on the changes he’s witnessed here during the past four decades

Next year is the year of the rooster and it marks my fortieth year in Thailand. The question that I am most asked these days is, what has changed? Well, quite a lot really. Me for a start, I’ve changed.

When I look in the mirror now I see more of my father and grandfather than that skinny youth that stepped off the DC-8 from London. That was the day the door opened and I first pushed my way through the heavy air-curtain, down the steps and across the tarmac into a humid world full of the pungent smells of spice, garlic and chilli peppers that told me I had arrived at Bangkok’s Don Muang airport.

When I look in the mirror now I see more of my father and grandfather than that skinny youth that stepped off the DC-8 from London. That was the day the door opened and I first pushed my way through the heavy air-curtain, down the steps and across the tarmac into a humid world full of the pungent smells of spice, garlic and chilli peppers that told me I had arrived at Bangkok’s Don Muang airport.

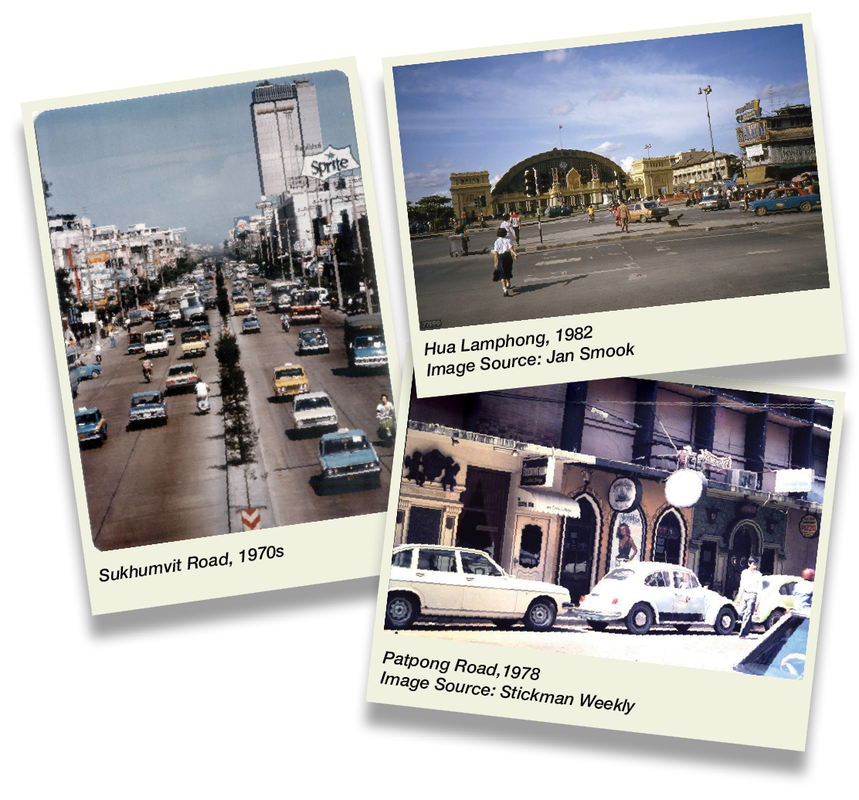

It was 1977 and I couldn’t wait for my new life to start. My first introduction to the mysterious East was the long airport road surrounded by open fields and only two lanes for the heavy traffic. Taxis didn’t have air-conditioning in those days and the doors were typically held closed with a bungee cord. Your taxi would reach the city after a very long game of chicken with the ten-wheel trucks and unless you were a recovering alcoholic you needed a drink immediately on arrival at your destination.

So, what has changed most since I got here? The people were much friendlier for a start. I think my Thai friends were happier then, even though they often lacked much. Thailand was called the Land of Smiles for a very good reason; nowhere in the world did people smile as much as they did in Thailand. It was contagious and really rather wonderful.

The Thais were famously polite and the girls were generally very shy and getting one to go out with you was quite an accomplishment. Televisions were mostly black and white and there wasn’t an invisible Pokemon behind every noodle vendor. What on earth is a Pokemon anyway? I would ask somebody but they’ve all got their faces buried deep in their mobile phones.

In my day, there was a three-year waiting list to get a telephone installed in your house, and then a two hour wait to make a ‘long distance’ call to Pattaya. Everything happens much faster now and sometimes it makes me quite dizzy. It’s a very modern city today and I often find it hard to relax or construct a thought. I fear I have become that thing of legends - the grumpy old expatriate.

I remember that the Bangkok skyline was relatively flat and there were trees and canals everywhere. Believe it or not, Bangkok used to be called the Venice of the East. There’s not much evidence to support that title now, even the tree-lined canal in the middle of Sathorn Road is long gone and its wooden houses have been knocked down to make way for even more luxury hotels.

Thailand was high on character and low on luxury in the 1970s. Only the houses of the rich had air-conditioning and then only in the bedrooms. The downstairs of the big houses had rattan furniture, large windows, and hanging ceiling fans. Kitchens were always outside the main house and everyone had a garden. I remember that every street had a pack of feral dogs and taking a stroll required never, never, never, showing even a hint of cowardice. The monsoons sent the dogs to shelter I know not where, and brought endless days of floods. Rolling up your trousers and carrying your shoes in your hand was the annual norm and we all did it.

All international business communication was done by a telex machine at the front desk of your nearest grand hotel. It was 360 Baht to send a single paragraph (the cost of a good night out) and your message typically said, “If you don’t send money soon I won’t be able to afford to send you any more telexes.” Waiting for a reply required daily visits to the hotel to check for your name amongst the entire business community’s pile of correspondence.

So, what has changed most since I got here? The people were much friendlier for a start. I think my Thai friends were happier then, even though they often lacked much. Thailand was called the Land of Smiles for a very good reason; nowhere in the world did people smile as much as they did in Thailand. It was contagious and really rather wonderful.

The Thais were famously polite and the girls were generally very shy and getting one to go out with you was quite an accomplishment. Televisions were mostly black and white and there wasn’t an invisible Pokemon behind every noodle vendor. What on earth is a Pokemon anyway? I would ask somebody but they’ve all got their faces buried deep in their mobile phones.

In my day, there was a three-year waiting list to get a telephone installed in your house, and then a two hour wait to make a ‘long distance’ call to Pattaya. Everything happens much faster now and sometimes it makes me quite dizzy. It’s a very modern city today and I often find it hard to relax or construct a thought. I fear I have become that thing of legends - the grumpy old expatriate.

I remember that the Bangkok skyline was relatively flat and there were trees and canals everywhere. Believe it or not, Bangkok used to be called the Venice of the East. There’s not much evidence to support that title now, even the tree-lined canal in the middle of Sathorn Road is long gone and its wooden houses have been knocked down to make way for even more luxury hotels.

Thailand was high on character and low on luxury in the 1970s. Only the houses of the rich had air-conditioning and then only in the bedrooms. The downstairs of the big houses had rattan furniture, large windows, and hanging ceiling fans. Kitchens were always outside the main house and everyone had a garden. I remember that every street had a pack of feral dogs and taking a stroll required never, never, never, showing even a hint of cowardice. The monsoons sent the dogs to shelter I know not where, and brought endless days of floods. Rolling up your trousers and carrying your shoes in your hand was the annual norm and we all did it.

All international business communication was done by a telex machine at the front desk of your nearest grand hotel. It was 360 Baht to send a single paragraph (the cost of a good night out) and your message typically said, “If you don’t send money soon I won’t be able to afford to send you any more telexes.” Waiting for a reply required daily visits to the hotel to check for your name amongst the entire business community’s pile of correspondence.

Surawong Road, 1970s

Surawong Road, 1970s When the reply eventually came and if you were lucky enough to receive good news it meant several journeys to the Bangkok Bank head office on Suapa Road in Chinatown. You had to go there in person and sit around for hours waiting for somebody to tell you your overseas transfer had arrived. All in all it was a rather pointless odyssey because the answer was always an aggressive no.

This was a constant brush with poverty because the process of convincing them that somewhere in their building was a stack of money with your name on typically took six weeks, if you were lucky. It was as if the only way to get paid was to convince them you weren’t going to give up, and I never gave up.

The expatriate community was small then and we all kept running into each other. The Vietnam War had just ended and the Bangkok food and drink scene was monopolised by the Americans and the French. Eggs over easy for breakfast and coq au vin for dinner washed down with dry martinis when you were flush, or fried rice with Mekong whiskey and Coke when the Bangkok Bank head office was dragging its feet.

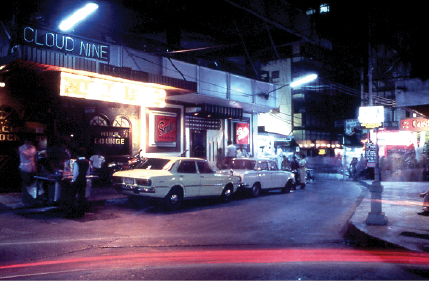

Everybody who was anybody would eventually show up at the Bamboo Bar at the Oriental Hotel and we all went to listen to the jazz band at the Napoleon, or Tony Aguilar playing the grand piano and crooning at the Balcony on New Road. Patpong was where everybody went in those days and where you got to hang out with Vietnam War veterans, professional gamblers, remittance men, conmen, war correspondents and spooks. They were not hard to spot because they were the ones that weren’t wearing bikinis.

The red light district was extremely bohemian and that small road that connects Silom and Suriwongse had airline offices, barbershops, restaurants, and even a bookshop back then.

There was always an illegal card game somewhere on the strip and between the legitimate businesses and offices it was also quite naughty. The name Patpong was famous all over the world. The few tourists that showed up in those days were green with envy. It’s all rather sordid now and I have long stopped going there.

Sadly, globalisation brought us more than cheddar cheese and draught Guinness. It also brought higher prices and debt. In my time I have seen Thailand change from a cash society to a credit society and I have seen the smiles wane. The breakdown of communities and the scattering of the family is the goal of all authoritarian financial systems. They have succeeded in much of the world already and are continuing to expand their influence.

In my four decades here I have seen Thailand go from a dozen family members living and eating together to people living lonely lives in shoeboxes without a safety net. Even the local family-owned shops and restaurants are gone, replaced by 7/11 stores and fast food outlets with minimum wage employees instead of self-employed members of the community. The loss of the local businesses in properties owned by the operators who lived upstairs, had a family car, and sent their children to good schools is an economic tragedy. There is no humanity in corporate monopolies whose purpose is the total removal of profits from the communities they feed off. Thailand’s neighborhoods are slowly dying from the parasites they host.

Don’t get me wrong, modernisation has brought endless benefits to the people of Thailand too, but I do wish it had come with some of the charm and generosity of spirit that made me fall in love with Thailand and its people. This brave new world kills everything that gets in its way, and that doesn’t bode well. Complexity is in vogue and the simplicities of yesterday are too often mocked.

I am not saying that things were better then, times were often hard, but we seemed much happier then, and the days felt longer and a lot less stressful. We are a modern society now and the telex has been replaced by handheld devices that make dreadful noises to remind us we have to react to every single piece of information, and that we must do it right now. Charcoal burners and woks are being replaced by microwave ovens and the shophouse is living its final days in the shadow of a high-rise building hungry to gobble up the land beneath it.

I am feeling nostalgic for the place that took me prisoner and captured my heart all those years ago. Do I still love Thailand? Yes I do, but it’s often a foreign country to me now.

This was a constant brush with poverty because the process of convincing them that somewhere in their building was a stack of money with your name on typically took six weeks, if you were lucky. It was as if the only way to get paid was to convince them you weren’t going to give up, and I never gave up.

The expatriate community was small then and we all kept running into each other. The Vietnam War had just ended and the Bangkok food and drink scene was monopolised by the Americans and the French. Eggs over easy for breakfast and coq au vin for dinner washed down with dry martinis when you were flush, or fried rice with Mekong whiskey and Coke when the Bangkok Bank head office was dragging its feet.

Everybody who was anybody would eventually show up at the Bamboo Bar at the Oriental Hotel and we all went to listen to the jazz band at the Napoleon, or Tony Aguilar playing the grand piano and crooning at the Balcony on New Road. Patpong was where everybody went in those days and where you got to hang out with Vietnam War veterans, professional gamblers, remittance men, conmen, war correspondents and spooks. They were not hard to spot because they were the ones that weren’t wearing bikinis.

The red light district was extremely bohemian and that small road that connects Silom and Suriwongse had airline offices, barbershops, restaurants, and even a bookshop back then.

There was always an illegal card game somewhere on the strip and between the legitimate businesses and offices it was also quite naughty. The name Patpong was famous all over the world. The few tourists that showed up in those days were green with envy. It’s all rather sordid now and I have long stopped going there.

Sadly, globalisation brought us more than cheddar cheese and draught Guinness. It also brought higher prices and debt. In my time I have seen Thailand change from a cash society to a credit society and I have seen the smiles wane. The breakdown of communities and the scattering of the family is the goal of all authoritarian financial systems. They have succeeded in much of the world already and are continuing to expand their influence.

In my four decades here I have seen Thailand go from a dozen family members living and eating together to people living lonely lives in shoeboxes without a safety net. Even the local family-owned shops and restaurants are gone, replaced by 7/11 stores and fast food outlets with minimum wage employees instead of self-employed members of the community. The loss of the local businesses in properties owned by the operators who lived upstairs, had a family car, and sent their children to good schools is an economic tragedy. There is no humanity in corporate monopolies whose purpose is the total removal of profits from the communities they feed off. Thailand’s neighborhoods are slowly dying from the parasites they host.

Don’t get me wrong, modernisation has brought endless benefits to the people of Thailand too, but I do wish it had come with some of the charm and generosity of spirit that made me fall in love with Thailand and its people. This brave new world kills everything that gets in its way, and that doesn’t bode well. Complexity is in vogue and the simplicities of yesterday are too often mocked.

I am not saying that things were better then, times were often hard, but we seemed much happier then, and the days felt longer and a lot less stressful. We are a modern society now and the telex has been replaced by handheld devices that make dreadful noises to remind us we have to react to every single piece of information, and that we must do it right now. Charcoal burners and woks are being replaced by microwave ovens and the shophouse is living its final days in the shadow of a high-rise building hungry to gobble up the land beneath it.

I am feeling nostalgic for the place that took me prisoner and captured my heart all those years ago. Do I still love Thailand? Yes I do, but it’s often a foreign country to me now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed