A brilliant new book about the country’s two-time former Prime Minister gives the inside story on what really went on behind the scenes during some of the most unforgettable and turbulent episodes in Thailand’s recent past.

By Colin Hastings

By Colin Hastings

Books written in English about Thailand’s recent past that are detailed and reliable are few and far between. This country, it seems, doesn’t do history, which is a major disappointment on many levels.

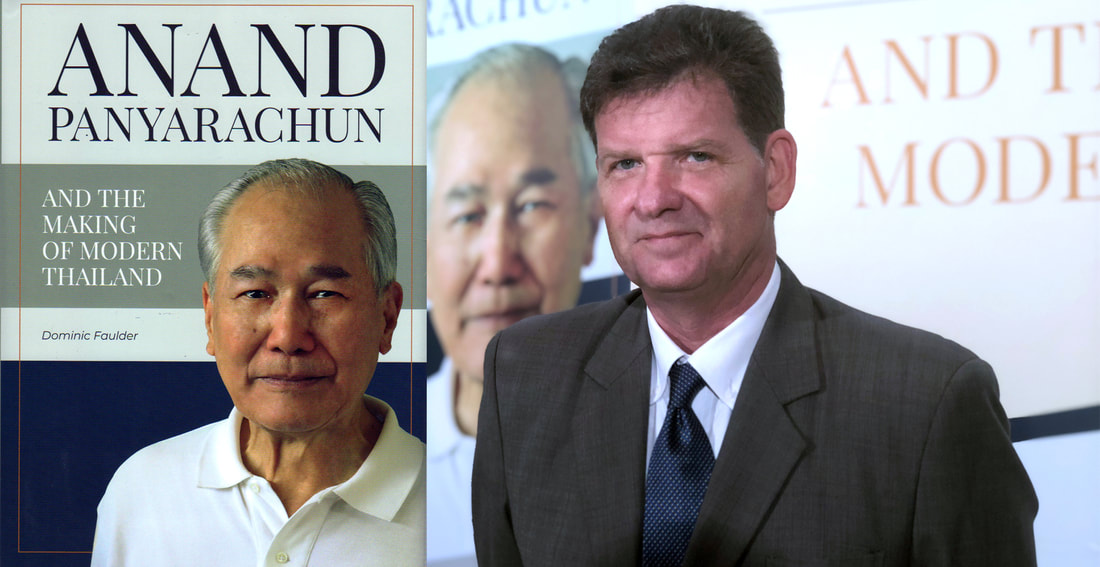

Fortunately, the recent publication of Dominic Faulder’s superbly crafted biography of two-time prime minister Anand Panyarachun goes a long way to filling many important gaps in the country’s history, from his birth in 1932 onwards. It provides credible answers to many of the questions that still haunt this nation, particularly the violent upheavals of its coup-prone past and how they were resolved. No one in Thailand today has been closer to the events that have shaped the country -- and indeed the entire region -- than Anand.

Maybe, just maybe, this magnificent endeavour by Faulder will inspire others to tell their stories honestly and openly. Thailand certainly needs greater self-analysis.

Called ‘Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand’, this monumental 600-page tome is an absolute must for anyone interested in the country’s political development and international relations over the past six decades. Driven, naturally enough, from Anand’s perspective, the book covers his personal experiences in all the major events of this period, including Thailand’s evolving relationship with China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the US, the fall of Indochina, the Thammasat massacre in 1976, and the military interventions that led to his rise in national prominence in the early 1990s.

Putting meat on the bones is a long and impressive cast of heavyweight characters who have played roles in the political, military, diplomatic, business, academic, and media sectors for many decades. Their contribution is in the form of numerous quotes that far exceed those from Anand, and they actually tell the story of the “making of modern Thailand” more effectively than the subject himself. The result is a unique and thoroughly fascinating insight into how this country has evolved.

Fortunately, the recent publication of Dominic Faulder’s superbly crafted biography of two-time prime minister Anand Panyarachun goes a long way to filling many important gaps in the country’s history, from his birth in 1932 onwards. It provides credible answers to many of the questions that still haunt this nation, particularly the violent upheavals of its coup-prone past and how they were resolved. No one in Thailand today has been closer to the events that have shaped the country -- and indeed the entire region -- than Anand.

Maybe, just maybe, this magnificent endeavour by Faulder will inspire others to tell their stories honestly and openly. Thailand certainly needs greater self-analysis.

Called ‘Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand’, this monumental 600-page tome is an absolute must for anyone interested in the country’s political development and international relations over the past six decades. Driven, naturally enough, from Anand’s perspective, the book covers his personal experiences in all the major events of this period, including Thailand’s evolving relationship with China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the US, the fall of Indochina, the Thammasat massacre in 1976, and the military interventions that led to his rise in national prominence in the early 1990s.

Putting meat on the bones is a long and impressive cast of heavyweight characters who have played roles in the political, military, diplomatic, business, academic, and media sectors for many decades. Their contribution is in the form of numerous quotes that far exceed those from Anand, and they actually tell the story of the “making of modern Thailand” more effectively than the subject himself. The result is a unique and thoroughly fascinating insight into how this country has evolved.

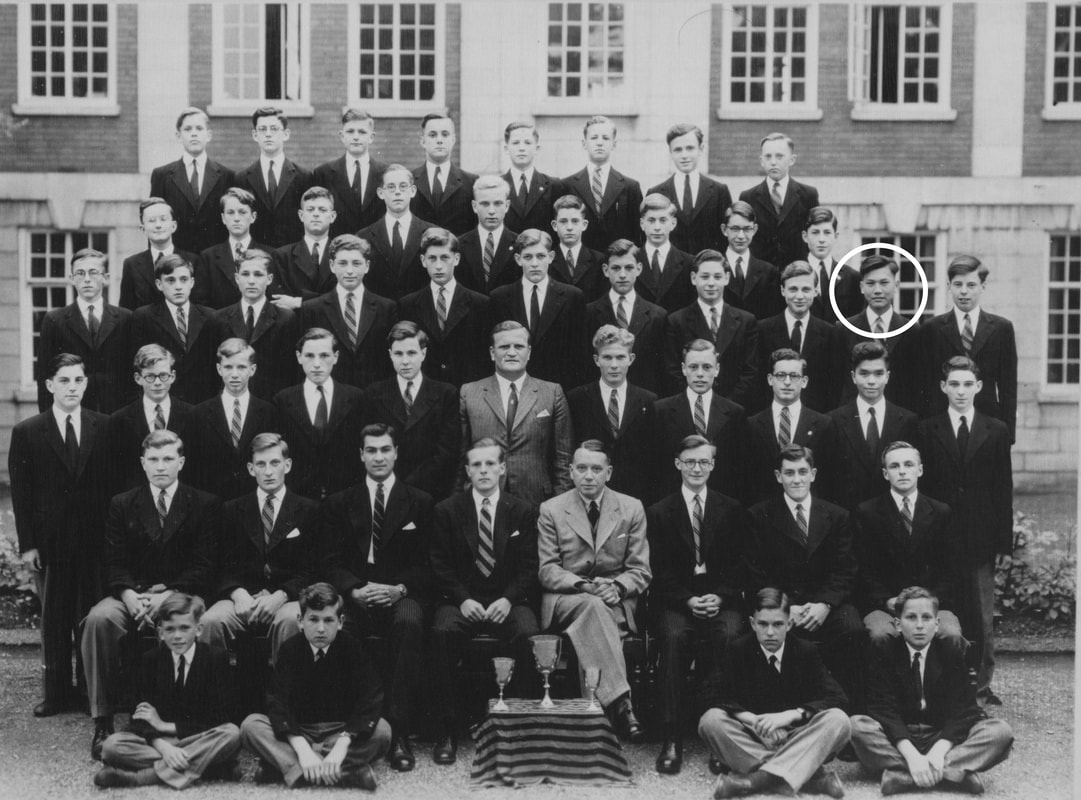

A British journalist, Faulder has chosen well for his first biography. Anand is a one-off. Born into a prominent Thai family, educated at two of Britain’s most distinguished institutions – Dulwich College and Cambridge University – his background and long career as an ambassador, permanent secretary of foreign affairs, his rare experience of business and industry, and his appointment, not once but twice, as the country’s prime minister, are unrivalled.

Anand’s international outlook, his honesty and integrity have always resonated with the global community.

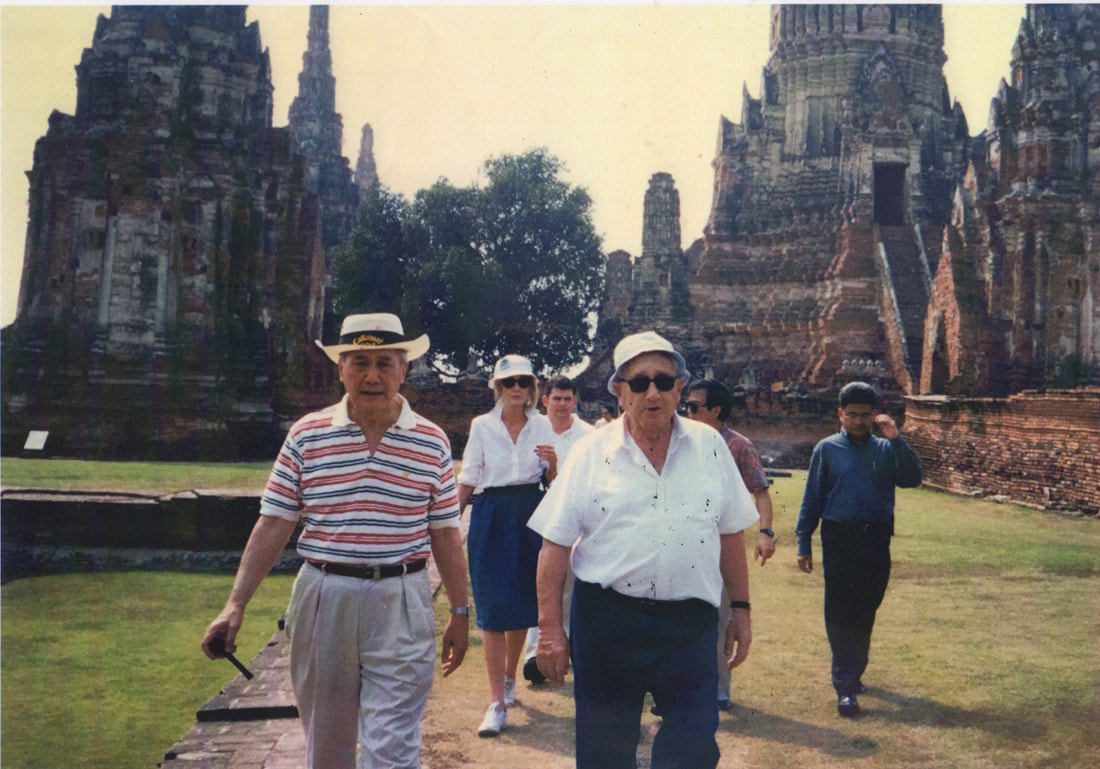

His popularity while operating at the highest levels of diplomacy in Canada, the US, Germany, and at the United Nations is indisputable. Despite the brevity of both his tenures as prime minister, he is credited with a remarkable number of improvements to the Thai economy and life in general, though it is not clear whether they were properly appreciated by Thais themselves. Nonetheless, his approach to the job most definitely caught the imagination of expatriate businessmen who sincerely believed they were witnessing the dawn of a new age in Thai bureaucracy and style of leadership. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be so.

Anand’s international outlook, his honesty and integrity have always resonated with the global community.

His popularity while operating at the highest levels of diplomacy in Canada, the US, Germany, and at the United Nations is indisputable. Despite the brevity of both his tenures as prime minister, he is credited with a remarkable number of improvements to the Thai economy and life in general, though it is not clear whether they were properly appreciated by Thais themselves. Nonetheless, his approach to the job most definitely caught the imagination of expatriate businessmen who sincerely believed they were witnessing the dawn of a new age in Thai bureaucracy and style of leadership. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be so.

| |

Anand’s life wasn’t without the odd setback, most notably the sinister accusations in 1976 of him being a communist sympathizer, which caused him to call an end to a distinguished career as a diplomat. Ironically, the military who wronged him then would later come running to him when they needed a prime minister. Critics have accused him of not being tough enough on the military after the ‘Black May’ violence in 1992, and also of being oblivious to military moves against the unions. It has even been claimed that he lacks ‘Thainess’ -- whatever that might be. Being in the spotlight in Thailand is clearly not easy.

The book has many highlights, but the chapter dealing with Black May in 1992 probably heads the field. It is a chilling tale of deep political unrest that rocked the country to its core, resulting in terrible violence that threatened a sustained period of instability. Faulder’s riveting description of the dramatic events that ultimately led to Anand being recalled as PM -- a return from the brink of disaster -- deserves a book and maybe even a movie of its own.

References to King Bhumibol Adulyadej, with whom Anand evidently enjoyed close but always respectful relations, are included in the narrative. Anand is still always careful not to betray confidences about the regular audiences he was given.

One book review has described Anand as “the best prime minister Thailand never elected”, which is hard to dispute. Anand himself describes his premiership as “one of the greatest accidents in history”, which is also true. He is, without question, one of the giants of Thai history who continues to enjoy enormous respect wherever he goes. Faulder’s book, meanwhile, is a magnificent achievement that should fuel much conversation among Thais too often deprived of information about their own history.

The book has many highlights, but the chapter dealing with Black May in 1992 probably heads the field. It is a chilling tale of deep political unrest that rocked the country to its core, resulting in terrible violence that threatened a sustained period of instability. Faulder’s riveting description of the dramatic events that ultimately led to Anand being recalled as PM -- a return from the brink of disaster -- deserves a book and maybe even a movie of its own.

References to King Bhumibol Adulyadej, with whom Anand evidently enjoyed close but always respectful relations, are included in the narrative. Anand is still always careful not to betray confidences about the regular audiences he was given.

One book review has described Anand as “the best prime minister Thailand never elected”, which is hard to dispute. Anand himself describes his premiership as “one of the greatest accidents in history”, which is also true. He is, without question, one of the giants of Thai history who continues to enjoy enormous respect wherever he goes. Faulder’s book, meanwhile, is a magnificent achievement that should fuel much conversation among Thais too often deprived of information about their own history.

Author Dominic Faulder on the background of ‘Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand’

Is this your first book?

No. It’s my first biography with my own byline. I have been involved in several other projects. For example, I co-edited and drafted large chunks of ‘King Bhumibol Adulyadej – A Life’s Work’ (KBA) in 2011, which has sold well and been translated into Thai.

How did your involvement in this project come about?

Anand chaired the KBA advisory board, and at meetings would often make references to his own experiences --

for example, what it was like to be in the room with Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the prime minister in the early 1960s.

Nicholas Grossman, the editor in chief at Editions Didier Millet, was very intrigued by all this and pushed the idea of a biography with Anand. Anand was frankly not too keen initially, and concerned about who could write it. He asked me how long I had been in Thailand, and I told him 30 years. We had already worked together on KBA, and I think he felt the book would need somebody with a long and balanced view of Thailand.

Did you expect the book to run to well over 500 pages?

It was originally supposed to be 80,000 words, but I soon realized I had bitten off rather more than I bargained for. When I discovered more about Anand’s remarkably long career, which took off in his twenties, I realized that I would have to include a great deal of historical context – a major challenge in this environment.

The book ballooned from a one-year project to six years and 250,000 words, and also became a parallel history.

Why Anand?

For Thais of a certain age, Anand has always been regarded as someone who represents the country well, and they are very proud of that. He’s clear-eyed, honest, genuinely selfless -- a true patriot without being oblivious to national shortcomings. He is able to say things almost nobody else can. Millennials know him less well.

He was born in 1932, the year of the revolutionary coup that ended Siam’s variant of absolute monarchy. His life bookends the long – some would say doomed -- struggle to establish constitutional democracy in Thailand. The late Jim Rooney, a prominent American businessman here for many years, called Anand’s premiership a ‘Camelot’ period. Whether it could have been sustainable had Anand stayed longer as prime minister is hard to say, but Anand himself never tried to stay longer. He actually gave back power twice. Think about that in a Thai context, and it is really quite remarkable.

In your view, what are the book’s highlights?

I actually like the way the book changes gear at different points, so I would be careful about declaring my preferences. Portraying the bucolic Bangkok of Anand’s childhood and the intrusion of World War II was a challenge. The Cold War and Vietnam War are seldom viewed from a Thai perspective, and I really hope this taster will encourage others to study these periods in more detail. The coup of 1991 that brought Anand to Government House is a pretty astonishing tale, with some very dark threads. The ‘Black May’ chapter which describes how Anand became prime minister a second time covers some new ground. The mechanisms that came into play at that time have never been well explained.

No. It’s my first biography with my own byline. I have been involved in several other projects. For example, I co-edited and drafted large chunks of ‘King Bhumibol Adulyadej – A Life’s Work’ (KBA) in 2011, which has sold well and been translated into Thai.

How did your involvement in this project come about?

Anand chaired the KBA advisory board, and at meetings would often make references to his own experiences --

for example, what it was like to be in the room with Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the prime minister in the early 1960s.

Nicholas Grossman, the editor in chief at Editions Didier Millet, was very intrigued by all this and pushed the idea of a biography with Anand. Anand was frankly not too keen initially, and concerned about who could write it. He asked me how long I had been in Thailand, and I told him 30 years. We had already worked together on KBA, and I think he felt the book would need somebody with a long and balanced view of Thailand.

Did you expect the book to run to well over 500 pages?

It was originally supposed to be 80,000 words, but I soon realized I had bitten off rather more than I bargained for. When I discovered more about Anand’s remarkably long career, which took off in his twenties, I realized that I would have to include a great deal of historical context – a major challenge in this environment.

The book ballooned from a one-year project to six years and 250,000 words, and also became a parallel history.

Why Anand?

For Thais of a certain age, Anand has always been regarded as someone who represents the country well, and they are very proud of that. He’s clear-eyed, honest, genuinely selfless -- a true patriot without being oblivious to national shortcomings. He is able to say things almost nobody else can. Millennials know him less well.

He was born in 1932, the year of the revolutionary coup that ended Siam’s variant of absolute monarchy. His life bookends the long – some would say doomed -- struggle to establish constitutional democracy in Thailand. The late Jim Rooney, a prominent American businessman here for many years, called Anand’s premiership a ‘Camelot’ period. Whether it could have been sustainable had Anand stayed longer as prime minister is hard to say, but Anand himself never tried to stay longer. He actually gave back power twice. Think about that in a Thai context, and it is really quite remarkable.

In your view, what are the book’s highlights?

I actually like the way the book changes gear at different points, so I would be careful about declaring my preferences. Portraying the bucolic Bangkok of Anand’s childhood and the intrusion of World War II was a challenge. The Cold War and Vietnam War are seldom viewed from a Thai perspective, and I really hope this taster will encourage others to study these periods in more detail. The coup of 1991 that brought Anand to Government House is a pretty astonishing tale, with some very dark threads. The ‘Black May’ chapter which describes how Anand became prime minister a second time covers some new ground. The mechanisms that came into play at that time have never been well explained.

Any comment about General Suchinda Kraprayoon’s disastrous assumption of the premiership in 1992, which led to bloodshed?

You really have to ask, “What was Suchinda thinking?” Apart from anything, it was a personal disaster that disgraced the military and resulted in its withdrawal from politics for 14 years. The lessons of military political interventions have evidently not been learned, however.

How did you get on with Anand during the writing of the book?

Very well. He has a good sense of humour, and is very open to discussion. There were more than 60 meetings when we would go back and forth, trawling his memory banks. It was certainly not a standard journalistic exercise or confrontational. I was trying to find things out, not catch him out. There were things he had forgotten over the years, and others that surprised him. For example, he did not know that Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s prime minister, tried to help him in 1976 when the foreign ministry was being purged after the Thammasat student massacre.

Could a Thai have written this book?

Of course, but perhaps that is the wrong question. A better question might be to ask why more Thais have not been writing books like this. Partly it is to do with literary traditions here, which I discuss on a few occasions. There are also enormous institutional barriers to overcome and myths that need to be dispelled. Thailand, like other countries in Southeast Asia, has a fascinating history, much of it still waiting to be uncovered. I hope I have trapped a little of that in this book, and that it will be a small stepping stone for others.

Anand is known as a straight-talker. Was that an impediment in any way?

Not at all. It’s one of his qualities, and refreshing in an environment where too often things are left unsaid. He didn’t censor me, but he did counsel me on some treacherous areas. He likes to shake the tree and let the truth drop out. If he was mistaken about something, he would be happy for clarification. He is very easy to get along with in that sense, and also has an immense appetite for work once he gets on board with a project.

So you got on well?

Yes, no problem at all. No arguments, but a few sparks did fly on the KBA project. He was very generous with his time and attention, and never testy about how long the project was taking. I sensed that his interest actually increased as time went by, and as it turned into something far more ambitious than originally envisaged.

Did you imagine the book would take so much time and effort?

The main problem with writing a detailed book is sustaining it. You can’t just gorge on the juicy bits. It can be a lonely process, and if it starts to overcome you the best thing is to stand back for a while and then re-engage with the material – the proverbial ‘good night’s sleep’

but a bit longer. Of course, the publisher had plenty of sleepless nights worrying that the project might never be completed. Fortunately, Anand’s life is a compelling subject, and this drove the project. How many people have had such interesting and varied experiences?

You really have to ask, “What was Suchinda thinking?” Apart from anything, it was a personal disaster that disgraced the military and resulted in its withdrawal from politics for 14 years. The lessons of military political interventions have evidently not been learned, however.

How did you get on with Anand during the writing of the book?

Very well. He has a good sense of humour, and is very open to discussion. There were more than 60 meetings when we would go back and forth, trawling his memory banks. It was certainly not a standard journalistic exercise or confrontational. I was trying to find things out, not catch him out. There were things he had forgotten over the years, and others that surprised him. For example, he did not know that Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s prime minister, tried to help him in 1976 when the foreign ministry was being purged after the Thammasat student massacre.

Could a Thai have written this book?

Of course, but perhaps that is the wrong question. A better question might be to ask why more Thais have not been writing books like this. Partly it is to do with literary traditions here, which I discuss on a few occasions. There are also enormous institutional barriers to overcome and myths that need to be dispelled. Thailand, like other countries in Southeast Asia, has a fascinating history, much of it still waiting to be uncovered. I hope I have trapped a little of that in this book, and that it will be a small stepping stone for others.

Anand is known as a straight-talker. Was that an impediment in any way?

Not at all. It’s one of his qualities, and refreshing in an environment where too often things are left unsaid. He didn’t censor me, but he did counsel me on some treacherous areas. He likes to shake the tree and let the truth drop out. If he was mistaken about something, he would be happy for clarification. He is very easy to get along with in that sense, and also has an immense appetite for work once he gets on board with a project.

So you got on well?

Yes, no problem at all. No arguments, but a few sparks did fly on the KBA project. He was very generous with his time and attention, and never testy about how long the project was taking. I sensed that his interest actually increased as time went by, and as it turned into something far more ambitious than originally envisaged.

Did you imagine the book would take so much time and effort?

The main problem with writing a detailed book is sustaining it. You can’t just gorge on the juicy bits. It can be a lonely process, and if it starts to overcome you the best thing is to stand back for a while and then re-engage with the material – the proverbial ‘good night’s sleep’

but a bit longer. Of course, the publisher had plenty of sleepless nights worrying that the project might never be completed. Fortunately, Anand’s life is a compelling subject, and this drove the project. How many people have had such interesting and varied experiences?

|

How did you manage to juggle your time with a full-time job?

I managed. There were blockages when I needed to talk to people, or do other work. The book developed at its own pace. In 2015 and 2016, we met only four or five times. In the last year, I saw him 15 times. Did you have research assistants? Yes, and excellent translators too. They were essential. For example, finding Anand’s speech to parliament after he returned to office took ages. We weren’t so lucky with Henry Kissinger’s speech when he came here in 1998 at Anand’s invitation. Nobody kept a record of his address at an AmCham lunch. Astonishing. How long did the actual writing take? I would constantly rewrite and reorder the drafts – as many as 150 for some chapters. Sequencing is very important to ensure the reader does not get lost or baffled by some inclusion in an odd place. Editors, readers, and proof readers were also involved. I was always very interested in what they spotted, didn’t understand, or thought was off the mark. Writing is a form of madness – you are constantly talking to yourself. Having others involved in the process is therapeutic. What was the most interesting period covered by the book? The years 1975-76 were pivotal for this country in a very important part of the world at the time. The 1991-92 chapters perhaps say more about why Thailand fails and succeeds than any others I can think of. |

Dominic Faulder: Originally from London, Dominic Faulder has been based in Bangkok since the early 1980s and has worked for numerous news organisations and publications. He was a special correspondent with the Hong Kong newsweekly Asiaweek for many years, and had particular involvement in the coverage of Burma/Myanmar and Cambodia in the 1980s and 1990s. He has been an associate editor with the Tokyo-based Nikkei Asian Review since 2014. |

Other than Anand, who was your best source of information?

I interviewed in different ways over a hundred people -- a few of whom asked not to be acknowledged at the front. Every one of them added something to the book. I am not going to tell you who declined to be interviewed, because that is their privilege and they had their own reasons. Some were simply too old and infirm to be able to help me. This book was never intended to be about attacking others or settling scores. Anand jokes about having made friends over the past twenty years of all his enemies, but he has also simply outlived the vast majority of significant personalities in his life. That is what happens to people who have meteoric rises early in their careers.

Having written this book, you must be very well informed about Thai history.

At the outset, I suppose my knowledge was slightly better than average, but I actually used to dislike reporting Thailand -- I was much more associated with Cambodia and Burma/Myanmar. Working on this project of course made me aware of how much I did not know. I was also concerned that all the material Anand and others around him were carrying might be lost.

How has the book been received, here and overseas?

Nearly four months since the launch and getting on for 60% of the first run has been sold following mainly domestic and regional reviews. Because it goes beyond Anand’s life story, I hope it will have a long shelf life as a resource for people who want to know how Thailand was shaped in the late 20th century. The book should be available on Amazon in April, and it will be interesting to see how it does overseas, particularly in the US where there are such strong connections. The next step would be a paperback edition to chase after the student market and more general readers. Translating this kind of work is a very tough proposition, but I hope it will happen one day.

Would you do it all over again?

I have no regrets, but I shall look a lot more carefully before I leap if another opportunity arises.

What’s next?

I am doing a lot a more journalism than editing now for my magazine, the Nikkei Asian Review. It is all quiet on the book front at the moment, but longer term there are three or four interesting topics, all rather different. One is a historical tale from the Vietnam War era; another might best be described as political science fiction, and it goes well beyond Southeast Asia. I have no plans for another biography at present, but if I did one it would involve a team of smart young researchers to help with the heavy lifting. KBA took just eight months to complete with 14 writers, so there is a lesson to be had there.

Writing books – is it lucrative?

No. Terrible!

How do you see Anand now?

Perhaps the question should be how will others see Anand now. He once joked, “I suppose you now know me better than anyone else in the world.” That’s obviously not true, but I was struck when his daughters told me that they had learned new things about their father’s life.

I interviewed in different ways over a hundred people -- a few of whom asked not to be acknowledged at the front. Every one of them added something to the book. I am not going to tell you who declined to be interviewed, because that is their privilege and they had their own reasons. Some were simply too old and infirm to be able to help me. This book was never intended to be about attacking others or settling scores. Anand jokes about having made friends over the past twenty years of all his enemies, but he has also simply outlived the vast majority of significant personalities in his life. That is what happens to people who have meteoric rises early in their careers.

Having written this book, you must be very well informed about Thai history.

At the outset, I suppose my knowledge was slightly better than average, but I actually used to dislike reporting Thailand -- I was much more associated with Cambodia and Burma/Myanmar. Working on this project of course made me aware of how much I did not know. I was also concerned that all the material Anand and others around him were carrying might be lost.

How has the book been received, here and overseas?

Nearly four months since the launch and getting on for 60% of the first run has been sold following mainly domestic and regional reviews. Because it goes beyond Anand’s life story, I hope it will have a long shelf life as a resource for people who want to know how Thailand was shaped in the late 20th century. The book should be available on Amazon in April, and it will be interesting to see how it does overseas, particularly in the US where there are such strong connections. The next step would be a paperback edition to chase after the student market and more general readers. Translating this kind of work is a very tough proposition, but I hope it will happen one day.

Would you do it all over again?

I have no regrets, but I shall look a lot more carefully before I leap if another opportunity arises.

What’s next?

I am doing a lot a more journalism than editing now for my magazine, the Nikkei Asian Review. It is all quiet on the book front at the moment, but longer term there are three or four interesting topics, all rather different. One is a historical tale from the Vietnam War era; another might best be described as political science fiction, and it goes well beyond Southeast Asia. I have no plans for another biography at present, but if I did one it would involve a team of smart young researchers to help with the heavy lifting. KBA took just eight months to complete with 14 writers, so there is a lesson to be had there.

Writing books – is it lucrative?

No. Terrible!

How do you see Anand now?

Perhaps the question should be how will others see Anand now. He once joked, “I suppose you now know me better than anyone else in the world.” That’s obviously not true, but I was struck when his daughters told me that they had learned new things about their father’s life.

KEY MOMENTS IN THE BOOK: CHAPTER 14 - ‘Black May’ – the 1992 turbulence that led to Anand’s second premiership

The May events happened partly because of Anand – in a good way, comments Ammar Siamwalla, one of Thailand’s most distinguished economists, as he reflects on the jagged military-civilian divide at that time.

“The military came and made a big song and dance about Chatichai being corrupt. The one thing they did wrong from their point of view was to appoint Anand. I think Anand showed the Thai people– at least the middle classes among the demonstrators in May – that a clean government was possible. When all the shuffling was done, the military wanted to go back to the old style. It was exactly the same type of government that Chatichai left except that it was headed by General Suchinda. That’s why the May events happened. People were mad. They had been through the coup and all that, and nothing changed zero.”

It is difficult to overstate the sense of foreboding that had remained prior to Anand’s second appointment, even with Suchinda gone. There had been killing; the country was rudderless; there was no break in the clouds. The State Department in Washington had told its diplomats in Bangkok to do the rounds of the political parties and encourage dialogue and democratic solutions. Although there was concern at the embassy that this might appear as undue interference, they had their orders and duly met with leading politicians Chuan, Banharn, Chatichai, Chavalit, and others. Preachers of democracy always have it far easier than aspiring practitioners.

“It was very depressing,” recalls Skip Boyce, the political counsellor at the US embassy who made the political rounds. “Noboby knew what was going to happen.” On that pivotal night, when everyone had expected Somboon to be appointed, it was Boyce’s job to file the cable to Washington as soon as the proclamation came through. Boyce remembers tuning into a local television station that opened its nightly news bulletin with a furiously spinning globe. It always made him dizzy. The channel flashed up images of Anand involved in some kind of ceremony. Boyce’s initial reaction was irritation: a careless technician must have used an old tape by mistake, he thought. Then there was a shot of Somboon disappearing upstairs at his home, and the realisation of what had actually just transpired dawned on the political counsellor. “How embarrassing was that?” Boyce remembers thinking.

For Arsa Sarasin – Anand’s foreign minister in 1991 and again in 1992 – this was the second time he had watched Anand become prime minister on television with no advance warning.

The mood at Thammasat was exceptionally sombre that night.

“We had been through a lot, and it was quite painful because of the killing,” recalls former student activist Karuna Buakamsri. “I watched Somboon Rahong dressed in white at his house and thought ‘I almost got killed, and we end up with this guy.’”

“The military came and made a big song and dance about Chatichai being corrupt. The one thing they did wrong from their point of view was to appoint Anand. I think Anand showed the Thai people– at least the middle classes among the demonstrators in May – that a clean government was possible. When all the shuffling was done, the military wanted to go back to the old style. It was exactly the same type of government that Chatichai left except that it was headed by General Suchinda. That’s why the May events happened. People were mad. They had been through the coup and all that, and nothing changed zero.”

It is difficult to overstate the sense of foreboding that had remained prior to Anand’s second appointment, even with Suchinda gone. There had been killing; the country was rudderless; there was no break in the clouds. The State Department in Washington had told its diplomats in Bangkok to do the rounds of the political parties and encourage dialogue and democratic solutions. Although there was concern at the embassy that this might appear as undue interference, they had their orders and duly met with leading politicians Chuan, Banharn, Chatichai, Chavalit, and others. Preachers of democracy always have it far easier than aspiring practitioners.

“It was very depressing,” recalls Skip Boyce, the political counsellor at the US embassy who made the political rounds. “Noboby knew what was going to happen.” On that pivotal night, when everyone had expected Somboon to be appointed, it was Boyce’s job to file the cable to Washington as soon as the proclamation came through. Boyce remembers tuning into a local television station that opened its nightly news bulletin with a furiously spinning globe. It always made him dizzy. The channel flashed up images of Anand involved in some kind of ceremony. Boyce’s initial reaction was irritation: a careless technician must have used an old tape by mistake, he thought. Then there was a shot of Somboon disappearing upstairs at his home, and the realisation of what had actually just transpired dawned on the political counsellor. “How embarrassing was that?” Boyce remembers thinking.

For Arsa Sarasin – Anand’s foreign minister in 1991 and again in 1992 – this was the second time he had watched Anand become prime minister on television with no advance warning.

The mood at Thammasat was exceptionally sombre that night.

“We had been through a lot, and it was quite painful because of the killing,” recalls former student activist Karuna Buakamsri. “I watched Somboon Rahong dressed in white at his house and thought ‘I almost got killed, and we end up with this guy.’”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed