But don’t panic – new building codes safeguard the capital. Now other cities in Thailand need similar measures

By Maxmilian Wechsler

By Maxmilian Wechsler

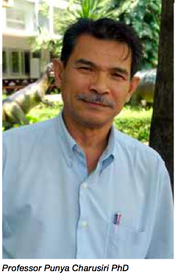

What’s more, according to one of the country’s foremost experts on earthquakes, Associate Professor Punya Charusiri, Head of Research Unit for Earthquake and Tectonic Geology at Chulalongkorn University, it served as a warning that Bangkok itself could be devastated at some time in the future because of the composition of the ground underneath the city.

The Thai Meteorological Department (TMD) said the May 5 earthquake measured 6.3 on the Richter scale, while the United States Geological Survey (USGS) put it at 6.0. Either way, it was one of the strongest ever in Thailand.

The epicenter was pinpointed at nine kilometers south of Mae Lao district and 27 kilometers southwest of Chiang Rai, at 7.4 kilometers below surface. An 83-year-old woman was killed after a brick wall collapsed on her. Dozens were injured, mainly in Mae Lao district. Damage to property was extensive. Many homes, Buddhist temples, schools, hospitals and other buildings in Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai provinces were ravaged and large cracks appeared on roads. The main tremor was followed by several strong aftershocks as high as 5.0-5.2 on the Richter scale.

The Thai Meteorological Department (TMD) said the May 5 earthquake measured 6.3 on the Richter scale, while the United States Geological Survey (USGS) put it at 6.0. Either way, it was one of the strongest ever in Thailand.

The epicenter was pinpointed at nine kilometers south of Mae Lao district and 27 kilometers southwest of Chiang Rai, at 7.4 kilometers below surface. An 83-year-old woman was killed after a brick wall collapsed on her. Dozens were injured, mainly in Mae Lao district. Damage to property was extensive. Many homes, Buddhist temples, schools, hospitals and other buildings in Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai provinces were ravaged and large cracks appeared on roads. The main tremor was followed by several strong aftershocks as high as 5.0-5.2 on the Richter scale.

The powerful earthquake, which resulted from a shift along the Phayao fault line, came as no surprise to Prof Punya. Noted the veteran geologist whose work has focused on the study of earthquakes for some 15 years: “I like geology more than anything else and enjoy the research. I also worry about a strong earthquake day and night.

“There are other earthquake experts in Thailand, but we (at Chulalongkorn University) are lucky to have instruments that other universities don’t have.”

The professor first became interested in earthquakes as a third-year geology student. “During one class about 25 years ago, a Dutch professor lecturing about minerals was holding a simple wooden divider to measure seismic movements, and he suddenly said, ‘There’s an earthquake now, we have to leave the building immediately.’ I felt dizzy at the same time and rushed with the other students out of the building.

“The next day it was reported that an earthquake had occurred in Kanchanaburi province near the Khao Laem dam not far from Myanmar. Some people thought the tremor was caused by the dam. In fact, the dam was constructed near what I believe is an active fault, but when it was built no one knew that,” Prof Punya said.

WHEN a strong earthquake with its epicenter in Chiang Rai province struck at dawn on May 5, it was felt hundreds of kilometers to the south in Bangkok, notably in tall buildings. The damage was shown on Thai TV and newspaper front pages for several days and alarmed the public as well as government officials. It was an eye-opener. People realized that a previously unsuspected natural disaster could strike Thailand at any time without warning.

What’s more, according to one of the country’s foremost experts on earthquakes, Associate Professor Punya Charusiri, Head of Research Unit for Earthquake and Tectonic Geology at Chulalongkorn University, it served as a warning that Bangkok itself could be devastated at some time in the future because of the composition of the ground underneath the city.

“There are other earthquake experts in Thailand, but we (at Chulalongkorn University) are lucky to have instruments that other universities don’t have.”

The professor first became interested in earthquakes as a third-year geology student. “During one class about 25 years ago, a Dutch professor lecturing about minerals was holding a simple wooden divider to measure seismic movements, and he suddenly said, ‘There’s an earthquake now, we have to leave the building immediately.’ I felt dizzy at the same time and rushed with the other students out of the building.

“The next day it was reported that an earthquake had occurred in Kanchanaburi province near the Khao Laem dam not far from Myanmar. Some people thought the tremor was caused by the dam. In fact, the dam was constructed near what I believe is an active fault, but when it was built no one knew that,” Prof Punya said.

WHEN a strong earthquake with its epicenter in Chiang Rai province struck at dawn on May 5, it was felt hundreds of kilometers to the south in Bangkok, notably in tall buildings. The damage was shown on Thai TV and newspaper front pages for several days and alarmed the public as well as government officials. It was an eye-opener. People realized that a previously unsuspected natural disaster could strike Thailand at any time without warning.

What’s more, according to one of the country’s foremost experts on earthquakes, Associate Professor Punya Charusiri, Head of Research Unit for Earthquake and Tectonic Geology at Chulalongkorn University, it served as a warning that Bangkok itself could be devastated at some time in the future because of the composition of the ground underneath the city.

Earthquakes occur almost daily in Chiang Rai province, and often several per day, but very rarely of this magnitude, continued the professor. “It was a wake-up call. A bigger tremor is likely to occur in the next millennium and it could have devastating effects on Bangkok even if it’s not centered under the capital.”

Prof Punya said the May 5 earthquake was shallow, about 7-10 kilometers below the surface. “The damage from a shallow earthquake is always more than from deep ones because the seismic energy will be transferred to the surface very quickly.”

He then explained that normally there is a sequence of tremors. The first tremors are usually mild. Then there is the main shock and then come the aftershocks. “We are not sure yet whether or not the 6.3 tremor was the main shock at that time. The main one could be much larger, maybe 9.0, and it would come very soon. We have to be very careful and cautious in this case.”

Prof Punya went to Chiang Rai after the May 5 earthquake to survey the damage. Many people were staying outdoors in tents on the advice of government agencies. Luckily, the epicenter was under rice fields, or the damage could have been much worse.

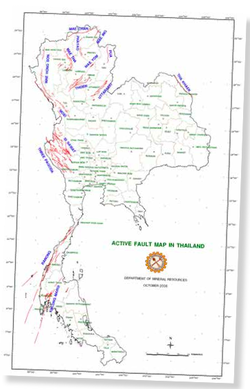

He explained that there are three seismically active regions in Thailand. The major one is in the north, the second is to the west and the third is in the southern peninsula. Most earthquakes occur in these three areas.

The faults in Myanmar near Thailand are much more dangerous than those in Thailand, said Prof Punya, adding that Cambodia and Laos also have some active faults. In the northern part of Thailand where the most earthquakes occur there are five active fault lines. “In the western part of Thailand there’s what we call the Three Pagoda fault in Kanchanaburi province, located quite far from Kanchanaburi town.

“There is also a long and big active fault running from Phang Nga province to Phuket. That fault is called Khlong Marui fault by the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

“There was also a magnitude 5.0 earthquake at Prachuap Khiri Khan’s offshore area that originated in the Gulf of Thailand seven years ago. Before that we didn’t believe that there were any active faults under the Gulf of Thailand. Now we realize that there is an active fault called Ranong fault which is almost parallel to the northeast-southwest trending Khlong Marui fault.”

He then explained that normally there is a sequence of tremors. The first tremors are usually mild. Then there is the main shock and then come the aftershocks. “We are not sure yet whether or not the 6.3 tremor was the main shock at that time. The main one could be much larger, maybe 9.0, and it would come very soon. We have to be very careful and cautious in this case.”

Prof Punya went to Chiang Rai after the May 5 earthquake to survey the damage. Many people were staying outdoors in tents on the advice of government agencies. Luckily, the epicenter was under rice fields, or the damage could have been much worse.

He explained that there are three seismically active regions in Thailand. The major one is in the north, the second is to the west and the third is in the southern peninsula. Most earthquakes occur in these three areas.

The faults in Myanmar near Thailand are much more dangerous than those in Thailand, said Prof Punya, adding that Cambodia and Laos also have some active faults. In the northern part of Thailand where the most earthquakes occur there are five active fault lines. “In the western part of Thailand there’s what we call the Three Pagoda fault in Kanchanaburi province, located quite far from Kanchanaburi town.

“There is also a long and big active fault running from Phang Nga province to Phuket. That fault is called Khlong Marui fault by the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

“There was also a magnitude 5.0 earthquake at Prachuap Khiri Khan’s offshore area that originated in the Gulf of Thailand seven years ago. Before that we didn’t believe that there were any active faults under the Gulf of Thailand. Now we realize that there is an active fault called Ranong fault which is almost parallel to the northeast-southwest trending Khlong Marui fault.”

Bangkok’s seismic sensitivity

“There is no record of an earthquake with its epicenter near Bangkok,” said the professor, “but we can sometimes feel tremors from elsewhere in Thailand or Myanmar.

The composition of the earth under Bangkok and nearby regions consists of especially stiff clay, which goes to a depth of about 7-15 meters from the surface.

“The stiff clay can increase the power of a seismic wave. Under the surface in Bangkok, there’s clay, a marine stiff clay layer. This composition of mud makes earthquakes that may occur outside of Bangkok dangerous in the future.

“Once a strong seismic wave comes here it can be increased more than in the epicenter itself. It is like if you turn the volume up on your radio. Therefore, Bangkok is more dangerous in terms of its geological parameters than Chiang Rai because there we don’t have that stiff layer of clay like in Bangkok,” said Prof Punya.

Such a seismic wave could come from the west in Kanchanaburi province, which on April 22, 1983 experienced a 5.9 earthquake with its epicenter at Bo Phloi in Kanchanaburi, only 120 kilometers from Bangkok. Alternatively a seismic wave could come from the east, via the Ongkarak fault, which still doesn’t appear on the map of the DMR, the agency responsible for keeping track of active faults in Thailand.

“The Ongkrak fault is a southward extension of the main Mae Ping fault or the so-called Moei-Uthai Thani fault by DMR which runs from the north around the Mae Ping River in Tak province. The Ongkarak fault was discovered recently by a research team from Chulalongkorn University.

“It could make Bangkok vulnerable to seismic danger. If an earthquake occurs in the southern part of this fault then it will definitely be felt in Bangkok,” warned Prof Punya.

There is also a very real chance of catastrophe in the north. “Chiang Rai is in more danger than we think. Before May 5 we had predicted the maximum earthquake for the Phayao fault in Chiang Rai to be about 5.5, not 6.0. This is serious because the direction of the fault is going north toward Chiang Rai city. We had thought that Phayao was a simple, very small fault that was not likely to cause any major damage.”

Prof Punya also mentioned that mountainous areas of Thailand were vulnerable to landslides as a result of earthquakes.

The strongest earthquake ever felt in Thailand measured 6.9 on the Richter scale and occurred in eastern Shan State near Mae Sai, Chiang Rai province, on March 24, 2007. A 6.3 earthquake was recorded in Chiang Khong, Chiang Rai province, on May 16, 2007.

“There is no record of an earthquake with its epicenter near Bangkok,” said the professor, “but we can sometimes feel tremors from elsewhere in Thailand or Myanmar.

The composition of the earth under Bangkok and nearby regions consists of especially stiff clay, which goes to a depth of about 7-15 meters from the surface.

“The stiff clay can increase the power of a seismic wave. Under the surface in Bangkok, there’s clay, a marine stiff clay layer. This composition of mud makes earthquakes that may occur outside of Bangkok dangerous in the future.

“Once a strong seismic wave comes here it can be increased more than in the epicenter itself. It is like if you turn the volume up on your radio. Therefore, Bangkok is more dangerous in terms of its geological parameters than Chiang Rai because there we don’t have that stiff layer of clay like in Bangkok,” said Prof Punya.

Such a seismic wave could come from the west in Kanchanaburi province, which on April 22, 1983 experienced a 5.9 earthquake with its epicenter at Bo Phloi in Kanchanaburi, only 120 kilometers from Bangkok. Alternatively a seismic wave could come from the east, via the Ongkarak fault, which still doesn’t appear on the map of the DMR, the agency responsible for keeping track of active faults in Thailand.

“The Ongkrak fault is a southward extension of the main Mae Ping fault or the so-called Moei-Uthai Thani fault by DMR which runs from the north around the Mae Ping River in Tak province. The Ongkarak fault was discovered recently by a research team from Chulalongkorn University.

“It could make Bangkok vulnerable to seismic danger. If an earthquake occurs in the southern part of this fault then it will definitely be felt in Bangkok,” warned Prof Punya.

There is also a very real chance of catastrophe in the north. “Chiang Rai is in more danger than we think. Before May 5 we had predicted the maximum earthquake for the Phayao fault in Chiang Rai to be about 5.5, not 6.0. This is serious because the direction of the fault is going north toward Chiang Rai city. We had thought that Phayao was a simple, very small fault that was not likely to cause any major damage.”

Prof Punya also mentioned that mountainous areas of Thailand were vulnerable to landslides as a result of earthquakes.

The strongest earthquake ever felt in Thailand measured 6.9 on the Richter scale and occurred in eastern Shan State near Mae Sai, Chiang Rai province, on March 24, 2007. A 6.3 earthquake was recorded in Chiang Khong, Chiang Rai province, on May 16, 2007.

Build for the worst

Prof Punya said that based on geological history he believes it’s likely that an earthquake strong enough to do major damage in Thailand will occur. There is no reason to panic as it could happen 1,000 years from now. Nevertheless, it is crucial that building codes be strictly enforced and perhaps be made tougher.

“I am not an engineer, but I think building codes will surely be revised for the northern part of Thailand in light of the May 5 earthquake. After the tsunami in 2004 there was a big change in building codes for Bangkok and other areas because we realized that the city is not so safe. The changes increase construction costs by about 10 percent, which is not so much. They are not only to protect against earthquakes but also strong winds.

“The measures adopted include bigger, deeper and stronger columns and strengthening joints with a special carbon strap so that when there’s a strong tremor the building will not collapse.

“People in Thailand don’t worry too much about earthquakes until one happens. Even government officials tell me that a big earthquake happens only once in a blue moon and there is no reason to worry. Officials are worried much more about extreme weather events like the flooding and drought caused by El Niño.

“But as I have said, if an earthquake is shallow it has much more potential for damage, and all earthquakes that have occurred with an epicenter in Thailand for the last year and a half have been shallow.

“Something that we also have to be much more aware of is the potential for another devastating tsunami, which could occur at any time because of an earthquake outside Thailand. There’s also a possibility that a tsunami will come from a volcanic explosion, like in August 1883 when Krakatoa erupted on an Indonesian island. It generated a series of devastating tsunamis, some as high as 35 meters.”

Warning systems are now installed along Thailand’s Andaman coast following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami which killed more than 200,000 people. Prof Punya stressed that such warning systems should be in place along the Gulf of Thailand as well.

“We don’t have any tsunami warning system installed in Pattaya because the authorities believe that a big tsunami will never occur in the Gulf of Thailand.

“There is much less chance than around the Andaman, but there have been small tsunamis recorded in the Gulf of Thailand, and it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

Field work

Prof Punya is frequently asked to consult in the planning of large projects to safeguard them against damage from earthquakes. “One large construction company in Laos involved in building a dam wanted to know whether a fault is located in the area. They asked me to help them to evaluate the risks of an earthquake, so I went there and investigated for the active fault.

“No evidence of the active fault is recognized at present. However, several pieces of geological and geochronological evidence show that the Xayaburi city (a small city in Lao People’s Democratic Republic) is surrounded by several sets of active faults. But they are not the long ones and can trigger an earthquake with the magnitude of 5.0 to 6.0.

“I am also working with the Electric Generation Authority of Thailand and with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment to assess which faults in Thailand are active. I also investigate faults together with some professors and students from my university and my former students who are now at other universities.

“To check for faults can be done pretty quickly, but to determine if a fault is active takes time, around a year,” said Prof Punya. “We also want to know about the present movement of the fault. When a sizable earthquake occurs, my team and I have to go and investigate. We take instrument readings and take samples, which means ‘trenching.’ The Department of Mineral Resources is responsible for keeping track of the active faults in Thailand. Our university provides the information to them.”

Prof Punya said that based on geological history he believes it’s likely that an earthquake strong enough to do major damage in Thailand will occur. There is no reason to panic as it could happen 1,000 years from now. Nevertheless, it is crucial that building codes be strictly enforced and perhaps be made tougher.

“I am not an engineer, but I think building codes will surely be revised for the northern part of Thailand in light of the May 5 earthquake. After the tsunami in 2004 there was a big change in building codes for Bangkok and other areas because we realized that the city is not so safe. The changes increase construction costs by about 10 percent, which is not so much. They are not only to protect against earthquakes but also strong winds.

“The measures adopted include bigger, deeper and stronger columns and strengthening joints with a special carbon strap so that when there’s a strong tremor the building will not collapse.

“People in Thailand don’t worry too much about earthquakes until one happens. Even government officials tell me that a big earthquake happens only once in a blue moon and there is no reason to worry. Officials are worried much more about extreme weather events like the flooding and drought caused by El Niño.

“But as I have said, if an earthquake is shallow it has much more potential for damage, and all earthquakes that have occurred with an epicenter in Thailand for the last year and a half have been shallow.

“Something that we also have to be much more aware of is the potential for another devastating tsunami, which could occur at any time because of an earthquake outside Thailand. There’s also a possibility that a tsunami will come from a volcanic explosion, like in August 1883 when Krakatoa erupted on an Indonesian island. It generated a series of devastating tsunamis, some as high as 35 meters.”

Warning systems are now installed along Thailand’s Andaman coast following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami which killed more than 200,000 people. Prof Punya stressed that such warning systems should be in place along the Gulf of Thailand as well.

“We don’t have any tsunami warning system installed in Pattaya because the authorities believe that a big tsunami will never occur in the Gulf of Thailand.

“There is much less chance than around the Andaman, but there have been small tsunamis recorded in the Gulf of Thailand, and it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

Field work

Prof Punya is frequently asked to consult in the planning of large projects to safeguard them against damage from earthquakes. “One large construction company in Laos involved in building a dam wanted to know whether a fault is located in the area. They asked me to help them to evaluate the risks of an earthquake, so I went there and investigated for the active fault.

“No evidence of the active fault is recognized at present. However, several pieces of geological and geochronological evidence show that the Xayaburi city (a small city in Lao People’s Democratic Republic) is surrounded by several sets of active faults. But they are not the long ones and can trigger an earthquake with the magnitude of 5.0 to 6.0.

“I am also working with the Electric Generation Authority of Thailand and with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment to assess which faults in Thailand are active. I also investigate faults together with some professors and students from my university and my former students who are now at other universities.

“To check for faults can be done pretty quickly, but to determine if a fault is active takes time, around a year,” said Prof Punya. “We also want to know about the present movement of the fault. When a sizable earthquake occurs, my team and I have to go and investigate. We take instrument readings and take samples, which means ‘trenching.’ The Department of Mineral Resources is responsible for keeping track of the active faults in Thailand. Our university provides the information to them.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed