After showing great restraint when rebels took over the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok four months earlier, the Thai government gets tough – with deadly results

By Maxmilian Wechsler

| SEVENTEEN years ago, a newly formed armed militant group calling itself Vigorous Burmese Student Warriors (VBSW) shocked Thailand and the world when they took over the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok. After negotiations with Thai authorities the militants released all hostages unharmed and were given safe passage back to Myanmar (see The BigChilli February issue). Four months later, in January 2000, VBSW joined hands with a band of armed ethnic Karen guerilla fighters known as God’s Army to storm a district hospital in Ratchaburi province, with a far bloodier outcome. With the fate of hundreds of hostages in the balance, Thai security forces ended a tense 22-hour standoff by laying siege to the hospital with overwhelming force and firepower. When it was over all hostages were freed unharmed, but all 10 rebels were dead. |

| Early on Monday, January 24, 2000, the 10 heavily armed men – seven from God’s Army and three from VBSW – hijacked a school bus near Takolan village, about seven kilometres from the Thai-Myanmar border in Suan Phung district of Ratchaburi province. They forced the driver to take them 65 kilometres to Ratchaburi town, where they debarked at the walled six-acre, 770-bed provincial hospital around 7.30am. The rebels were wearing camouflage outfits and had their faces covered with balaclavas, dark masks or scarves. Some wore berets or floppy bush hats. They were armed with assault rifles, hand grenades and Claymore mines. The driver said that they first commanded him to drive to Bangkok, but when they saw the hospital they said to stop here. “I thought that they had no plan,” said the driver, adding that they had passed through 10 military and police checkpoints on the road, but none were manned. |

This is hard to understand. At that time the road from Takolan to Ratchaburi was under tight security and motorists expected to be stopped along the way. Sometimes they were told to open the boot and submit to a full vehicle search. It’s odd that a bus with 10 foreigners dressed as they were and carrying war weapons made it to downtown Ratchaburi without being detected.

Upon arriving at the hospital grounds the guerrillas immediately took control, firing their automatic weapons repeatedly into the air. Radio reports said a teacher from a nearby school was slightly wounded by a stray bullet. The militants, who shared one mobile phone, issued a warning that the front of the main hospital building had been mined and threatened to start killing hostages if Thai commandos stormed the facility.

A photo of a Claymore directional anti-personnel mine placed near the main entrance to the hospital was later published, with the English words “Front Toward Enemy” clearly visible. The mines are designed to be detonated remotely.

The guerrillas likely obtained them from the Karen National Union (KNU). According to one KNU senior member, the group’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army, were at that time in the possession of Claymore mines made in the United Kingdom.

Health officials estimated that up to 1,200 people were inside the hospital, about 200 of these hospital staff and the rest patients and visitors. The attackers at first herded all the doctors and nurses into the emergency room, but later allowed them to move around the hospital to tend to patients. Doctors in the hospital confirmed that the gunmen placed mines in the compound and threatened to harm their captives if security forces came too close.

Many very ill patients, pregnant women, children, and elderly people were among the hostages. Some were seen crawling to safety, carrying their intravenous drips down ladders set up outside of back windows. It was a heart-breaking scene. General

Surayud Chulanont, Commander of the Royal Thai Army made it known that as a professional soldier he found the hospital seizure reprehensible, noting that even in wartime hospitals are regarded as neutral ground and attacking a hospital is considered a crime against humanity.

Rapid response

As word of the attack spread police closed outbound lines of the wide highway from Bangkok into Ratchaburi town to allow hundreds of police cars, ambulances and other emergency vehicles, as well as government officials and Thai media, to reach the hospital quickly.

Soldiers from nearby military bases rushed to the scene, joined by Special Force troops from Lopburi. Soon hundreds of police and soldiers surrounded the hospital, establishing a 300-metre ‘no-go zone’ around the perimeter. The Governor of Ratchaburi province, Komain Daengthongdee ordered the evacuation of nearby administrative offices and schools. Thai Deputy Prime Minister Kon Thappharangsi appealed to the guerrillas not to harm anyone inside the hospital, saying: “I want to tell those who seized the hospital that it is not right to use patients for bargaining.”

The guerrillas issued a five-point list of demands including medical care for their fighters injured in recent clashes with Myanmar military troops. They also wanted Thai authorities to grant about 200 God’s Army soldiers refuge in Thailand and demanded that the Thai government persuade Myanmar to halt its offensive against God’s Army.

In the afternoon, Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai chaired a meeting of Thailand’s anti-terrorism committee on how to deal with the crisis. Speaking after the meeting General Surayud said he had ordered his troops to stop shelling guerrilla bases on the Myanmar border, another of the hostage takers’ demands. He also agreed to open Thailand’s western border to God’s Army soldiers seeking medical treatment in exchange for the safe release of all the hostages.

However, Thai officials did not agree to the militants’ demands to supply them with two helicopters and guarantee safe passage out of the country. The guerrillas were asking for a team of 10 doctors and communications equipment to go with them in the helicopters.

Déjà vu

When the reports of the hospital takeover appeared in the local media, memories of the seizure of the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok in October 1999 were still fresh. People were surprised and outraged that Myanmar militants were bringing their struggle to Thailand again. The situation at the hospital was beamed live to viewers in Thailand and around the world. The siege became a top international news story and by nightfall hundreds of reporters swarmed the hospital.

Leaders of Myanmar exile groups based in Thailand were just as surprised as everyone else, and frantically called one another to try to get information on the attackers. What they found out was passed on to Thai authorities. The Myanmar exile community in Thailand faced harsh reprisals after the embassy siege, and the leaders were very distressed to see another international incident that would likely damage their causes and relations with the host country.

As the army commander raced to the scene from Bangkok, the government immediately established a negotiating team led by Interior Minister Sanan Kachornprasart. While negotiations were in progress, during the day until late at night the gunmen released about 70 hostages made up of the seriously ill, elderly, women, and children. Another 17 hostages escaped by a back door. They were taken to one of two command centres for debriefing. A police source said more than 100 hostages had probably managed to flee the building without the knowledge of the authorities.

A Thai TV cameraman was allowed to enter one of the buildings occupied by the guerrillas. His live broadcast showed frightened hostages, some hugging each other, and guerrillas walking around them brandishing assault rifles.

Upon arriving at the hospital grounds the guerrillas immediately took control, firing their automatic weapons repeatedly into the air. Radio reports said a teacher from a nearby school was slightly wounded by a stray bullet. The militants, who shared one mobile phone, issued a warning that the front of the main hospital building had been mined and threatened to start killing hostages if Thai commandos stormed the facility.

A photo of a Claymore directional anti-personnel mine placed near the main entrance to the hospital was later published, with the English words “Front Toward Enemy” clearly visible. The mines are designed to be detonated remotely.

The guerrillas likely obtained them from the Karen National Union (KNU). According to one KNU senior member, the group’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army, were at that time in the possession of Claymore mines made in the United Kingdom.

Health officials estimated that up to 1,200 people were inside the hospital, about 200 of these hospital staff and the rest patients and visitors. The attackers at first herded all the doctors and nurses into the emergency room, but later allowed them to move around the hospital to tend to patients. Doctors in the hospital confirmed that the gunmen placed mines in the compound and threatened to harm their captives if security forces came too close.

Many very ill patients, pregnant women, children, and elderly people were among the hostages. Some were seen crawling to safety, carrying their intravenous drips down ladders set up outside of back windows. It was a heart-breaking scene. General

Surayud Chulanont, Commander of the Royal Thai Army made it known that as a professional soldier he found the hospital seizure reprehensible, noting that even in wartime hospitals are regarded as neutral ground and attacking a hospital is considered a crime against humanity.

Rapid response

As word of the attack spread police closed outbound lines of the wide highway from Bangkok into Ratchaburi town to allow hundreds of police cars, ambulances and other emergency vehicles, as well as government officials and Thai media, to reach the hospital quickly.

Soldiers from nearby military bases rushed to the scene, joined by Special Force troops from Lopburi. Soon hundreds of police and soldiers surrounded the hospital, establishing a 300-metre ‘no-go zone’ around the perimeter. The Governor of Ratchaburi province, Komain Daengthongdee ordered the evacuation of nearby administrative offices and schools. Thai Deputy Prime Minister Kon Thappharangsi appealed to the guerrillas not to harm anyone inside the hospital, saying: “I want to tell those who seized the hospital that it is not right to use patients for bargaining.”

The guerrillas issued a five-point list of demands including medical care for their fighters injured in recent clashes with Myanmar military troops. They also wanted Thai authorities to grant about 200 God’s Army soldiers refuge in Thailand and demanded that the Thai government persuade Myanmar to halt its offensive against God’s Army.

In the afternoon, Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai chaired a meeting of Thailand’s anti-terrorism committee on how to deal with the crisis. Speaking after the meeting General Surayud said he had ordered his troops to stop shelling guerrilla bases on the Myanmar border, another of the hostage takers’ demands. He also agreed to open Thailand’s western border to God’s Army soldiers seeking medical treatment in exchange for the safe release of all the hostages.

However, Thai officials did not agree to the militants’ demands to supply them with two helicopters and guarantee safe passage out of the country. The guerrillas were asking for a team of 10 doctors and communications equipment to go with them in the helicopters.

Déjà vu

When the reports of the hospital takeover appeared in the local media, memories of the seizure of the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok in October 1999 were still fresh. People were surprised and outraged that Myanmar militants were bringing their struggle to Thailand again. The situation at the hospital was beamed live to viewers in Thailand and around the world. The siege became a top international news story and by nightfall hundreds of reporters swarmed the hospital.

Leaders of Myanmar exile groups based in Thailand were just as surprised as everyone else, and frantically called one another to try to get information on the attackers. What they found out was passed on to Thai authorities. The Myanmar exile community in Thailand faced harsh reprisals after the embassy siege, and the leaders were very distressed to see another international incident that would likely damage their causes and relations with the host country.

As the army commander raced to the scene from Bangkok, the government immediately established a negotiating team led by Interior Minister Sanan Kachornprasart. While negotiations were in progress, during the day until late at night the gunmen released about 70 hostages made up of the seriously ill, elderly, women, and children. Another 17 hostages escaped by a back door. They were taken to one of two command centres for debriefing. A police source said more than 100 hostages had probably managed to flee the building without the knowledge of the authorities.

A Thai TV cameraman was allowed to enter one of the buildings occupied by the guerrillas. His live broadcast showed frightened hostages, some hugging each other, and guerrillas walking around them brandishing assault rifles.

|

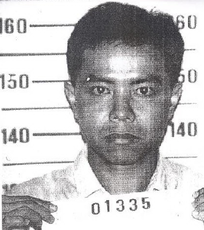

REPORTS OF DEATH GREATLY EXAGGERATED Quoting ‘dissident sources’ one exile website gave a list of names of the militants killed by security forces at Ratchaburi hospital. One of these was Ye Thi Ha, alias Sai Naing, leader of the VBSW. Some media also reported that he was among the dead, but this is incorrect. One prominent exile says with certainty that he met Ye Thi Ha at a food outlet at Bangkok’s Victory Monument in 2004. Other Myanmar exiles confirmed that Ye This Ha would meet people there. One said: “He regards Thailand, especially Bangkok, as his second home. Until last year [2004], his favourite meeting place was a restaurant near the Victory Monument. I met him there once. At that time he wore his hair long and braided. I didn’t feel safe with him after he said the Thais were looking for him, so I left him immediately. “He is very clever and brave. Despite the risk of being captured by the Myanmar authorities, he entered the country disguised as a ladyboy and went to Mandalay and Yangon [Rangoon].” Ye Thi Ha was arrested in Thailand for hijacking a plane in October 1989 and for having war weapons and ammunition in November 1993. He had a reputation as an expert bomb maker and reportedly cooperated with a Western intelligence agency. Ye Thi Ha rented an apartment in Saphan Kwai not far from Victory Monument. When police finally located him they set up a raid on the apartment, but just as they were ready to burst in and arrest him, a call allegedly came from someone very high up telling them to back off. It seems that Ye Thi Ha was valuable to someone. He made the following announcement in an audio broadcast from the Democratic Voice of Burma on August 5, 2003: “As the Warriors, we will be mainly targeting the Myanmar generals who have been holding on to power and controlling the country, and we will keep on fighting them.” A source close to the VBSW said that in 2004 Ye Thi Ha asked compatriots living in the United States, Germany and France for a large amount of money, allegedly to produce sophisticated explosive devices. |

Hard line this time

Prime Minister Chuan met with Supreme Army Commander General Mongkol Ampornpisit at Government House that night, and afterward both men were rushed to Ratchaburi to attend another meeting at Bhanu Rangsi military camp. The PM emerged around 1am looking serious. He had already made the difficult decision to take a hard line this time against Myanmar militants who wanted to promote their case in Thailand: earlier that night he had given the order to storm the hospital.

While negotiations were still under way, about 40 commandos infiltrated the hospital compound under the cover of darkness dressed as patients or medical workers. They hid their weapons in the kitchen and quietly instructed hostages to turn off the lights and lie on the floor. A nurse who was held hostage later told a Thai TV crew that staff had received a phone call from security forces before the attack telling them to turn off all lights and not to move, whatever happened.

Sharpshooters with two-way radios were seen taking positions on the perimeter of the hospital. Around 9pm the rebels asked to meet with a BBC reporter and cameraman, but they had apparently already left the scene. Shortly after midnight, six children were released. Sporadic gunfire was heard from the hospital compound and there was a lot of activity in the area. Police commandos and military teams could be seen taking up positions. The throng of reporters was moved further back.

At about 5.30am two concussion grenades were set off at one corner of the compound to create a diversion and a signal. About 20 explosions rocked the hospital compound before first light, and under the cover of smoke bombs, the 70 to 80 commandos began their assault. They charged the main nine-storey hospital building, trading shots with the rebels as army helicopters circled overhead using spotlights to search for anyone trying to escape. The pre-dawn assault lasted for about an hour.

As the smoke cleared hundreds of shocked patients, many in stained hospital gowns, rushed out of the building. After the gunfire stopped, dozens of ambulances pulled up to the hospital to transport patients – some clearly exhausted and in great distress to other hospitals.

At around 9am the commandos emerged from the hospital. Freed hostages embraced them and the assembled media cheered them. Troops held back reporters who wanted to interview the hostages.

After the siege was over, explosives experts combed the compound with mine detectors. Later in the morning journalists were allowed inside the hospital compound to have a look around. They were also shown the weapons used by the guerrillas and the ten bodies wrapped in white sheets. They were buried immediately, with no autopsies performed.

What officials said

The PM, this time taking a hard line stand against Myanmar’s opposition forces who want to promote their case in Thailand, gave order to storm the hospital late on Monday night.

After the raid, officials said no patients or staff were injured; five members of the security forces apparently sustained minor wounds.

Mr Sanan said the guerrillas deserved their fate because they had brought so much trauma and suffering to the Thai people, especially to those in the hospital. Lieutenant General Taweep Suwannasingh, Commander of the First Army Region who also commanded the raid, told the assembled members of the media that security forces had no choice but to do whatever was necessary to save the hostages.

There were questions about the contrasting response from the Thai government compared to the VBSW takeover of the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok, when the Thai government conceded to all demands and flew the militants by helicopter to the Thai-Burma border.

Prasong Soonsiri, national security adviser to PM Chuan, said the assault should serve as a warning to other guerrilla organisations inside Myanmar and affirm to the government of Myanmar that Thailand would not tolerate terrorism. “This is a statement from Thailand that you can no longer do this kind of thing to us. If you [exiles] are hurt and need medical treatment, we are happy to help. But we won’t stand sieges.”

Myanmar’s military government praised Thailand for the “decisive” end to the siege by “terrorists”, in sharp contrast to the criticism of the handling of the embassy takeover.

Prime Minister Chuan met with Supreme Army Commander General Mongkol Ampornpisit at Government House that night, and afterward both men were rushed to Ratchaburi to attend another meeting at Bhanu Rangsi military camp. The PM emerged around 1am looking serious. He had already made the difficult decision to take a hard line this time against Myanmar militants who wanted to promote their case in Thailand: earlier that night he had given the order to storm the hospital.

While negotiations were still under way, about 40 commandos infiltrated the hospital compound under the cover of darkness dressed as patients or medical workers. They hid their weapons in the kitchen and quietly instructed hostages to turn off the lights and lie on the floor. A nurse who was held hostage later told a Thai TV crew that staff had received a phone call from security forces before the attack telling them to turn off all lights and not to move, whatever happened.

Sharpshooters with two-way radios were seen taking positions on the perimeter of the hospital. Around 9pm the rebels asked to meet with a BBC reporter and cameraman, but they had apparently already left the scene. Shortly after midnight, six children were released. Sporadic gunfire was heard from the hospital compound and there was a lot of activity in the area. Police commandos and military teams could be seen taking up positions. The throng of reporters was moved further back.

At about 5.30am two concussion grenades were set off at one corner of the compound to create a diversion and a signal. About 20 explosions rocked the hospital compound before first light, and under the cover of smoke bombs, the 70 to 80 commandos began their assault. They charged the main nine-storey hospital building, trading shots with the rebels as army helicopters circled overhead using spotlights to search for anyone trying to escape. The pre-dawn assault lasted for about an hour.

As the smoke cleared hundreds of shocked patients, many in stained hospital gowns, rushed out of the building. After the gunfire stopped, dozens of ambulances pulled up to the hospital to transport patients – some clearly exhausted and in great distress to other hospitals.

At around 9am the commandos emerged from the hospital. Freed hostages embraced them and the assembled media cheered them. Troops held back reporters who wanted to interview the hostages.

After the siege was over, explosives experts combed the compound with mine detectors. Later in the morning journalists were allowed inside the hospital compound to have a look around. They were also shown the weapons used by the guerrillas and the ten bodies wrapped in white sheets. They were buried immediately, with no autopsies performed.

What officials said

The PM, this time taking a hard line stand against Myanmar’s opposition forces who want to promote their case in Thailand, gave order to storm the hospital late on Monday night.

After the raid, officials said no patients or staff were injured; five members of the security forces apparently sustained minor wounds.

Mr Sanan said the guerrillas deserved their fate because they had brought so much trauma and suffering to the Thai people, especially to those in the hospital. Lieutenant General Taweep Suwannasingh, Commander of the First Army Region who also commanded the raid, told the assembled members of the media that security forces had no choice but to do whatever was necessary to save the hostages.

There were questions about the contrasting response from the Thai government compared to the VBSW takeover of the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok, when the Thai government conceded to all demands and flew the militants by helicopter to the Thai-Burma border.

Prasong Soonsiri, national security adviser to PM Chuan, said the assault should serve as a warning to other guerrilla organisations inside Myanmar and affirm to the government of Myanmar that Thailand would not tolerate terrorism. “This is a statement from Thailand that you can no longer do this kind of thing to us. If you [exiles] are hurt and need medical treatment, we are happy to help. But we won’t stand sieges.”

Myanmar’s military government praised Thailand for the “decisive” end to the siege by “terrorists”, in sharp contrast to the criticism of the handling of the embassy takeover.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed