By Maxmilian Wechsler

| WITH more and more people in Bangkok contracting dengue fever (DF), the myth that the disease was an upcountry phenomenon has been truly busted wide open. Although there are 19 provinces in Thailand regarded as active breeding areas of the Aedes mosquito which transmits the disease, most cases actually occur in ten of them in the central region. And they include Bangkok, where crowded communities offer abundant opportunities for the mosquitoes to breed. |

Tawat Ananthothai, 57, who lives in Bang Chak in the Phra Khanong district, is one of many Bangkokians who contracted DF last year. “One evening in the middle of August, I was at home watching television when I suddenly felt strange,” he said. “I went to bed, suspecting nothing serious, but the next day I felt even worse. I had a high fever, between 38-39C and felt little muscle-aches all over my body.

“At first I thought it was flu, and I took paracetamol for two days. The fever went down a little but I still didn’t feel good, so I went to see a doctor at a major Bangkok hospital on August 18. After examining me, she diagnosed me with flu and recommended that I stay in the hospital for a treatment, which I did.”

Mr Tawat was treated with antibiotics and more paracetamol. A blood test found that his platelet count was slightly low, a telltale sign of DF, but the doctor felt it was nothing to be concerned about. The hospital didn’t check his platelet count again before discharging him on August 20.

“That was their mistake,” said Mr Tawat. “I am sure my platelet count had dropped dramatically by then.

“The next day, I still didn’t feel very well. I spoke to a friend who is a doctor, and he advised me to get a complete blood count [CBC] analyzing my red and white cells and platelets.

“It was a good decision to talk to another doctor. If I had any kind of accident at that time, driving a car or just bumping into something while walking around, I could have bled to death. I strongly recommend that anyone with symptoms that could be DF ask their doctor to check specifically for it.

“I walked into another hospital and asked for the CBC. The result wasn’t very good. My platelet count was only 10,000 [per microliter of blood], which is very low. A platelet count under 50,000 is considered dangerous. My doctor told me to get admitted to the hospital immediately because my condition was serious and I could die.

“I was re-admitted to the first hospital on the same day and requested a specialist. Another blood test confirmed the low platelet count, and I received platelets administered intravenously into my arm. At that time I didn’t have a fever, so they didn’t give me any medicine. The specialist told me there is no drug to treat dengue, nor any vaccine to prevent it.

“I didn’t have other symptoms like vomiting or pain in my joints. One of my friends who contracted dengue fever about three years ago was pretty ill. He couldn’t eat or even drink. I felt fine in comparison.

“The next morning my platelet count had increased to 30,000 and on August 24 it was up to 35,000. I was discharged that day. Before I left, the specialist told me that there has been a big increase in the number of elderly people who are being infected with dengue; in the past, children were mostly the victims.

“She also stressed that the seriousness of the disease is due to its effect on platelets [which help to clot blood at the site of a wound]. If you have an accident or cut yourself when you have a low platelet count, you could actually bleed to death. While I was in the hospital, I wasn’t even allowed to brush my teeth because it might cause bleeding.”

By August 27, further blood tests showed Mr Tawat’s platelet count was over 150,000.

“When I tell my friends I contracted dengue, the first question they ask is where I got it. They are usually surprised when I tell them I hadn’t left Bangkok for many weeks. It apparently takes around two weeks from the time the infected mosquito bites you before the first symptoms appear,” explained Mr Tawat.

He said that no one from the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) came to spray his house and the surrounding area with insecticide as they are supposed to when a DF case is reported. According to regulations, every hospital in Bangkok must notify the BMA when they have a patient with dengue.

Rising global threat

DF is a viral disease transmitted by the bite of an Aedes mosquito infected with one of four viruses (see sidebar). Last year Thailand experienced its worst epidemic since 1987, with 152,768 cases of dengue resulting in 132 deaths. There were 48 reported deaths in 2012 and 45 in 2011. Health officials expect a slower dengue season this year due to an extended cool season.

The recent rise in DF cases is not restricted to Thailand. It is a global phenomenon thought to be linked to climate change. It has been detected in tropical and sub-tropical areas of Africa, Australia, the Caribbean basin, Central and South America, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and China. Southern parts of the United States are also hunting grounds for mosquitoes carrying the virus.

More than 2.5 billion people, around 40% of the global population, live in more than 100 countries where there is a risk of dengue transmission. About 1.8 billion of these are in Asia-Pacific countries, and tropical Southeast Asian nations are particularly vulnerable to DF.

Last year’s DF figures broke records all across Asia and Latin America. In Nicaragua, DF reached epidemic proportions, and the number of cases in India doubled from 2012. In Africa, outbreaks of DF were reported last year in Angola and Kenya. In Oceania, French Polynesia reported an outbreak and so did New Caledonia.

Most countries in South and Central America and the Caribbean also reported increased incidences of DF in 2013. Brazil reported three times the number of DF cases in comparison to the same period of 2012, and more cases were also recorded in Paraguay, Mexico, Nicaragua, French Guiana and Costa Rica. The Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin also reported increases in 2013.

Along with Thailand, in Southeast Asia, Laos, Malaysia and Singapore reported more cases in 2013.

“At first I thought it was flu, and I took paracetamol for two days. The fever went down a little but I still didn’t feel good, so I went to see a doctor at a major Bangkok hospital on August 18. After examining me, she diagnosed me with flu and recommended that I stay in the hospital for a treatment, which I did.”

Mr Tawat was treated with antibiotics and more paracetamol. A blood test found that his platelet count was slightly low, a telltale sign of DF, but the doctor felt it was nothing to be concerned about. The hospital didn’t check his platelet count again before discharging him on August 20.

“That was their mistake,” said Mr Tawat. “I am sure my platelet count had dropped dramatically by then.

“The next day, I still didn’t feel very well. I spoke to a friend who is a doctor, and he advised me to get a complete blood count [CBC] analyzing my red and white cells and platelets.

“It was a good decision to talk to another doctor. If I had any kind of accident at that time, driving a car or just bumping into something while walking around, I could have bled to death. I strongly recommend that anyone with symptoms that could be DF ask their doctor to check specifically for it.

“I walked into another hospital and asked for the CBC. The result wasn’t very good. My platelet count was only 10,000 [per microliter of blood], which is very low. A platelet count under 50,000 is considered dangerous. My doctor told me to get admitted to the hospital immediately because my condition was serious and I could die.

“I was re-admitted to the first hospital on the same day and requested a specialist. Another blood test confirmed the low platelet count, and I received platelets administered intravenously into my arm. At that time I didn’t have a fever, so they didn’t give me any medicine. The specialist told me there is no drug to treat dengue, nor any vaccine to prevent it.

“I didn’t have other symptoms like vomiting or pain in my joints. One of my friends who contracted dengue fever about three years ago was pretty ill. He couldn’t eat or even drink. I felt fine in comparison.

“The next morning my platelet count had increased to 30,000 and on August 24 it was up to 35,000. I was discharged that day. Before I left, the specialist told me that there has been a big increase in the number of elderly people who are being infected with dengue; in the past, children were mostly the victims.

“She also stressed that the seriousness of the disease is due to its effect on platelets [which help to clot blood at the site of a wound]. If you have an accident or cut yourself when you have a low platelet count, you could actually bleed to death. While I was in the hospital, I wasn’t even allowed to brush my teeth because it might cause bleeding.”

By August 27, further blood tests showed Mr Tawat’s platelet count was over 150,000.

“When I tell my friends I contracted dengue, the first question they ask is where I got it. They are usually surprised when I tell them I hadn’t left Bangkok for many weeks. It apparently takes around two weeks from the time the infected mosquito bites you before the first symptoms appear,” explained Mr Tawat.

He said that no one from the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) came to spray his house and the surrounding area with insecticide as they are supposed to when a DF case is reported. According to regulations, every hospital in Bangkok must notify the BMA when they have a patient with dengue.

Rising global threat

DF is a viral disease transmitted by the bite of an Aedes mosquito infected with one of four viruses (see sidebar). Last year Thailand experienced its worst epidemic since 1987, with 152,768 cases of dengue resulting in 132 deaths. There were 48 reported deaths in 2012 and 45 in 2011. Health officials expect a slower dengue season this year due to an extended cool season.

The recent rise in DF cases is not restricted to Thailand. It is a global phenomenon thought to be linked to climate change. It has been detected in tropical and sub-tropical areas of Africa, Australia, the Caribbean basin, Central and South America, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and China. Southern parts of the United States are also hunting grounds for mosquitoes carrying the virus.

More than 2.5 billion people, around 40% of the global population, live in more than 100 countries where there is a risk of dengue transmission. About 1.8 billion of these are in Asia-Pacific countries, and tropical Southeast Asian nations are particularly vulnerable to DF.

Last year’s DF figures broke records all across Asia and Latin America. In Nicaragua, DF reached epidemic proportions, and the number of cases in India doubled from 2012. In Africa, outbreaks of DF were reported last year in Angola and Kenya. In Oceania, French Polynesia reported an outbreak and so did New Caledonia.

Most countries in South and Central America and the Caribbean also reported increased incidences of DF in 2013. Brazil reported three times the number of DF cases in comparison to the same period of 2012, and more cases were also recorded in Paraguay, Mexico, Nicaragua, French Guiana and Costa Rica. The Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin also reported increases in 2013.

Along with Thailand, in Southeast Asia, Laos, Malaysia and Singapore reported more cases in 2013.

Geographic expansion

DF is not only showing increased incidence, it is also spreading geographically. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that the possibility of an outbreak of DF now exists in Europe and local transmission of dengue was reported for the first time in France and Croatia in 2010. In 2012, an outbreak of dengue in the Madeira Islands of Portugal resulted in over 2,000 cases, and imported cases were detected in 10 other European countries, apart from mainland Portugal.

The first homegrown case in seven decades was reported in Western Australia. An outbreak was reported for the first time in Bhutan in 2004. In November 2006, nine people were hospitalized for dengue in Nepal, but all cases had been contracted elsewhere.

While the mortality rate from DF is still significantly less than from HIV/Aids, heart disease and car accidents, health officials are understandably concerned. The WHO says the incidence of dengue has increased 30-fold over the last 50 years, and with almost half of the world’s population now at risk, the WHO implemented a strategic prevention plan for the Asia-Pacific region in 2008. The plan, which runs through 2015, aims to reduce the death rate to below 1% of the infected population and cut the number of dengue cases by 20% per year.

The WHO responds to dengue in many ways, such as supporting countries in the confirmation of outbreaks through a collaborating network of laboratories, and improving DF reporting systems to portray an accurate picture of the toll taken by the disease. It gathers official reports of dengue cases from over 100 member states and publishes guidelines and handbooks for case management, prevention and control. The WHO also develops tools to aid in the fight, including insecticides and new treatment applications and technologies.

Dengue in Asia

SOUTHEAST and Southern Asia are highly prone to DF epidemics, as transmission occurs year-round. The WHO records disease incidence every year in eight countries in the region: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Timor-Leste, where an outbreak with an unusually high fatality rate (3.55%) was first reported in 2005.

According to the WHO, DF was first reported in Thailand in 1949 and the first verified outbreak occurred in 1958, when there were 2,158 reported cases and 300 deaths. The country has had several major epidemics since then, including in 1987 when 174,285 cases were reported. However, the fatality rate at this time was a very low 0.58%.

The Ministry of Public Health closely cooperates and coordinates with the WHO and other international organizations, as well as with other Thai government agencies throughout the country, including the BMA. The ministry has been countering the outbreak by setting up operation centers in all districts of the country and launching campaigns to raise awareness of the disease.

All private hospitals in Bangkok have been directed to report each case directly to the BMA and not to the Ministry of Public Health. The BMA will afterward report to the ministry. When someone gets infected with the disease, the BMA should dispatch a rapid response team to investigate the case. If they verify that it is DF, they will then send another team to spray pesticide in the community.

At the start of 2013, the Thai cabinet ordered various ministries, including the Education and Interior ministries, to work out a vector control and surveillance program aimed at terminating the breeding grounds for dengue-carrying in mosquitoes. Hospitals nationwide are also on alert. So-called “dengue corners” have been set up at hospitals to screen patients with dengue-like symptoms to make a fast and efficient diagnosis.

According to experts and doctors, DF is a preventable disease, but even though Thailand has been fighting it for almost a half century infection is still common. Many cases are reported in remote, mountainous communities which are difficult to reach and where knowledge of disease prevention is poor and the vector control and surveillance program is absent. Some of these areas are inhabited by low-income minorities who are unable to afford mosquito repellent.

Adding to the challenges for the country’s healthcare sector, scientists have discovered a new type of the virus that causes dengue. The surprising find was announced during the Third Dengue Fever Conference held in Bangkok from October 21-23 last year. The new discovery is bound to complicate efforts to develop a vaccine against the persistent global menace.

DF is not only showing increased incidence, it is also spreading geographically. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that the possibility of an outbreak of DF now exists in Europe and local transmission of dengue was reported for the first time in France and Croatia in 2010. In 2012, an outbreak of dengue in the Madeira Islands of Portugal resulted in over 2,000 cases, and imported cases were detected in 10 other European countries, apart from mainland Portugal.

The first homegrown case in seven decades was reported in Western Australia. An outbreak was reported for the first time in Bhutan in 2004. In November 2006, nine people were hospitalized for dengue in Nepal, but all cases had been contracted elsewhere.

While the mortality rate from DF is still significantly less than from HIV/Aids, heart disease and car accidents, health officials are understandably concerned. The WHO says the incidence of dengue has increased 30-fold over the last 50 years, and with almost half of the world’s population now at risk, the WHO implemented a strategic prevention plan for the Asia-Pacific region in 2008. The plan, which runs through 2015, aims to reduce the death rate to below 1% of the infected population and cut the number of dengue cases by 20% per year.

The WHO responds to dengue in many ways, such as supporting countries in the confirmation of outbreaks through a collaborating network of laboratories, and improving DF reporting systems to portray an accurate picture of the toll taken by the disease. It gathers official reports of dengue cases from over 100 member states and publishes guidelines and handbooks for case management, prevention and control. The WHO also develops tools to aid in the fight, including insecticides and new treatment applications and technologies.

Dengue in Asia

SOUTHEAST and Southern Asia are highly prone to DF epidemics, as transmission occurs year-round. The WHO records disease incidence every year in eight countries in the region: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Timor-Leste, where an outbreak with an unusually high fatality rate (3.55%) was first reported in 2005.

According to the WHO, DF was first reported in Thailand in 1949 and the first verified outbreak occurred in 1958, when there were 2,158 reported cases and 300 deaths. The country has had several major epidemics since then, including in 1987 when 174,285 cases were reported. However, the fatality rate at this time was a very low 0.58%.

The Ministry of Public Health closely cooperates and coordinates with the WHO and other international organizations, as well as with other Thai government agencies throughout the country, including the BMA. The ministry has been countering the outbreak by setting up operation centers in all districts of the country and launching campaigns to raise awareness of the disease.

All private hospitals in Bangkok have been directed to report each case directly to the BMA and not to the Ministry of Public Health. The BMA will afterward report to the ministry. When someone gets infected with the disease, the BMA should dispatch a rapid response team to investigate the case. If they verify that it is DF, they will then send another team to spray pesticide in the community.

At the start of 2013, the Thai cabinet ordered various ministries, including the Education and Interior ministries, to work out a vector control and surveillance program aimed at terminating the breeding grounds for dengue-carrying in mosquitoes. Hospitals nationwide are also on alert. So-called “dengue corners” have been set up at hospitals to screen patients with dengue-like symptoms to make a fast and efficient diagnosis.

According to experts and doctors, DF is a preventable disease, but even though Thailand has been fighting it for almost a half century infection is still common. Many cases are reported in remote, mountainous communities which are difficult to reach and where knowledge of disease prevention is poor and the vector control and surveillance program is absent. Some of these areas are inhabited by low-income minorities who are unable to afford mosquito repellent.

Adding to the challenges for the country’s healthcare sector, scientists have discovered a new type of the virus that causes dengue. The surprising find was announced during the Third Dengue Fever Conference held in Bangkok from October 21-23 last year. The new discovery is bound to complicate efforts to develop a vaccine against the persistent global menace.

What you should know about Dengue

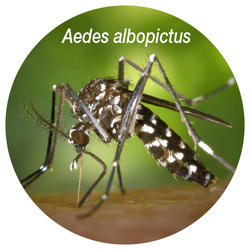

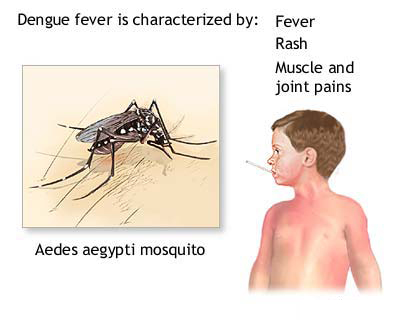

DENGUE fever (DF) is a flu-like viral infection transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected female mosquito of the Aedes aegypti (or Yellow Fever Mosquito) and Aedes albopictus (or Tiger Mosquito) species, found throughout the world. The incubation time can be anywhere from 3-14 days after the mosquito bites, but is most often 4-7 days. DF can be caused by any of the four types of dengue virus: DEN-1, 2, 3 or 4.

Scientists say that the Aedes mosquito’s lifespan has recently increased from one to two months. The mosquito is quite small and dark with white markings and banded legs. It usually lives indoors and near humans, its primary food source. The mosquito tends to rest in cool, shaded places in houses such as laundry areas, under tables and in wardrobes. It feeds during daylight hours, often biting people around the feet and ankles, bites repeatedly and is hard to catch. The bite is painless.

DENGUE fever (DF) is a flu-like viral infection transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected female mosquito of the Aedes aegypti (or Yellow Fever Mosquito) and Aedes albopictus (or Tiger Mosquito) species, found throughout the world. The incubation time can be anywhere from 3-14 days after the mosquito bites, but is most often 4-7 days. DF can be caused by any of the four types of dengue virus: DEN-1, 2, 3 or 4.

Scientists say that the Aedes mosquito’s lifespan has recently increased from one to two months. The mosquito is quite small and dark with white markings and banded legs. It usually lives indoors and near humans, its primary food source. The mosquito tends to rest in cool, shaded places in houses such as laundry areas, under tables and in wardrobes. It feeds during daylight hours, often biting people around the feet and ankles, bites repeatedly and is hard to catch. The bite is painless.

The Dengue virus can only be transmitted from mosquito-to-person, not person-to-person. Virus-carrying mosquitoes breed in clear water and can be often be found in and around housing developments. They are most active during the day.

DF is not a new disease. The first recorded mention of symptoms compatible with DF was in China during the Chin Dynasty (265-420 AD), when it was called a “water poison” and associated with insects.

DF was first isolated in 1943. During the last part of the 20th century, many tropical regions of the world saw an increase in dengue cases. Epidemics occurred more frequently and with more severity. In recent years, DF has become a major international public health concern. Currently dengue is the most important viral disease transmitted by

mosquitoes afflicting humans in the world context.

Symptoms of typical uncomplicated classic dengue usually start with fever and also include severe headache (mostly in the forehead), pain behind the eyes which worsens with eye movement, severe joint and muscle pains and aches, swollen lymph nodes, nausea, general weakness, sudden chills, vomiting and/or diarrhea, skin rash and loss of appetite.

DF is not a new disease. The first recorded mention of symptoms compatible with DF was in China during the Chin Dynasty (265-420 AD), when it was called a “water poison” and associated with insects.

DF was first isolated in 1943. During the last part of the 20th century, many tropical regions of the world saw an increase in dengue cases. Epidemics occurred more frequently and with more severity. In recent years, DF has become a major international public health concern. Currently dengue is the most important viral disease transmitted by

mosquitoes afflicting humans in the world context.

Symptoms of typical uncomplicated classic dengue usually start with fever and also include severe headache (mostly in the forehead), pain behind the eyes which worsens with eye movement, severe joint and muscle pains and aches, swollen lymph nodes, nausea, general weakness, sudden chills, vomiting and/or diarrhea, skin rash and loss of appetite.

Symptoms of Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF) include all of the symptoms of classic dengue plus marked damage to blood and lymph vessels, bleeding from nose, gums, or under the skin, resulting in purplish bruises. This form of dengue is more likely to cause death.

The most severe and dangerous form of the disease is Dengue Shock Syndrome. Symptoms include all those for DHF plus fluids leaking from blood vessels, massive bleeding and shock due to very low blood pressure. This generally occurs if an infected person goes to the hospital too late and the disease has affected many organs. However, some people may still survive, provided they are admitted to the intensive care unit where extensive treatment will be provided.

Persons suspected of having DF should see a doctor at once. There’s no specific medication to kill the virus but there’s no doubt that medical supervision saves lives, as with the administration of platelets. Most people will recover completely within about two weeks, but others experience several weeks to months of feeling tired and/or depressed.

To help with recovery, healthcare experts recommend getting plenty of bed rest, drinking lots of fluids and taking medicines to reduce fever, although some advise patients with DF not to take aspirin. For severe dengue symptoms, including shock and coma, early and aggressive emergency treatment with fluids and electrolyte replacement can be lifesaving. Some patients need transfusions to control bleeding.

The mosquitoes that transmit the dengue virus often breed in used automobile tires, flower pots, old oil drums and other man-made containers like earthenware jars, metal drums, concrete cisterns and discarded plastic containers. The infected mosquitoes may also live and rest indoors, in closets and other dark places. Outside, they rest where it is cool and shaded.

To prevent being bitten by the mosquito, avoid areas with standing water, wear long sleeve shirts, and long trousers or dresses during the daylight hours when the mosquito is most active. Other suggested preventive measures include the use of mosquito repellant sprays containing DEET, coils, electric vapor mats, window screens and mosquito nets.

The most severe and dangerous form of the disease is Dengue Shock Syndrome. Symptoms include all those for DHF plus fluids leaking from blood vessels, massive bleeding and shock due to very low blood pressure. This generally occurs if an infected person goes to the hospital too late and the disease has affected many organs. However, some people may still survive, provided they are admitted to the intensive care unit where extensive treatment will be provided.

Persons suspected of having DF should see a doctor at once. There’s no specific medication to kill the virus but there’s no doubt that medical supervision saves lives, as with the administration of platelets. Most people will recover completely within about two weeks, but others experience several weeks to months of feeling tired and/or depressed.

To help with recovery, healthcare experts recommend getting plenty of bed rest, drinking lots of fluids and taking medicines to reduce fever, although some advise patients with DF not to take aspirin. For severe dengue symptoms, including shock and coma, early and aggressive emergency treatment with fluids and electrolyte replacement can be lifesaving. Some patients need transfusions to control bleeding.

The mosquitoes that transmit the dengue virus often breed in used automobile tires, flower pots, old oil drums and other man-made containers like earthenware jars, metal drums, concrete cisterns and discarded plastic containers. The infected mosquitoes may also live and rest indoors, in closets and other dark places. Outside, they rest where it is cool and shaded.

To prevent being bitten by the mosquito, avoid areas with standing water, wear long sleeve shirts, and long trousers or dresses during the daylight hours when the mosquito is most active. Other suggested preventive measures include the use of mosquito repellant sprays containing DEET, coils, electric vapor mats, window screens and mosquito nets.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed