Mosquito-borne menace raises its head again in Southeast Asia hefty fines and even jail for property owners failing to get rid of mosquito larvae.

By MAXMILIAN WECHSLER

By MAXMILIAN WECHSLER

On June 14 last year Dr Sukhum Kanchanapimai, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), announced strong measures aimed at stopping the spread of dengue fever in Thailand: Owners of properties who fail to get rid of mosquito larvae are subject to jail terms of up to three years and/or a fine of up to 25,000 baht.

Thailand is not alone in taking aggressive action to fight a public health menace that takes a lethal toll in this part of the world during monsoon season. The Singaporean National Environmental Agency announced on June 22 for households who repeatedly fail to eradicate mosquito breeding areas will face harsher punishments. Three-time offenders are subject to a fine of up to S$5,000 (about 112,000 baht), or imprisonment for a term of three months, or both, for the first court conviction.

Even heavier penalties are levied on construction sites where mosquitoes are allowed to breed. The fine for first offence has been raised from $2,000 to $3,000; the fine for second offence has also been raised from $4,000, to $5,000. Three-time offenders must appear in court instead S$5,000 fine, where they face a fine not exceeding $20,000, or imprisonment up to three months, or both, for the first conviction. The new penalties went into effect on July 15.

Thailand is not alone in taking aggressive action to fight a public health menace that takes a lethal toll in this part of the world during monsoon season. The Singaporean National Environmental Agency announced on June 22 for households who repeatedly fail to eradicate mosquito breeding areas will face harsher punishments. Three-time offenders are subject to a fine of up to S$5,000 (about 112,000 baht), or imprisonment for a term of three months, or both, for the first court conviction.

Even heavier penalties are levied on construction sites where mosquitoes are allowed to breed. The fine for first offence has been raised from $2,000 to $3,000; the fine for second offence has also been raised from $4,000, to $5,000. Three-time offenders must appear in court instead S$5,000 fine, where they face a fine not exceeding $20,000, or imprisonment up to three months, or both, for the first conviction. The new penalties went into effect on July 15.

Media in Thailand and around the world are currently preoccupied with the struggle against the novel coronavirus known as COVID-19. But some public health officials caution that another disease spread by mosquitoes and once commonly referred to as ‘break-bone fever’ is not getting as much attention as it should. With the rainy season upon us dengue fever is once again set to take a grim annual toll in Thailand (see box ‘Ten year statistics’).

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease found in tropical and sub-tropical climates worldwide, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas. As with Covid-19, there is no specific treatment, vaccine or cure for any of the three types. However, early detection of disease progression associated and access to proper medical care have lowered the fatality rate of severe dengue to below 1%.

Dengue is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected female mosquito of the species Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) or sometimes Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquito), both found throughout the world and both able to live and reproduce inside and outside of homes. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes generally prefer to live indoors and near humans, their primary food source. They like to rest in cool, shaded places such as laundry areas, in closets, under tables and in wardrobes. Dengue-carrying mosquitoes may bite at any time of day, but mostly in early morning and evening. They often bite people around the feet and ankles, and reportedly are unable to fly higher than an adult’s knees and unable to breed if the temperature falls below 16C.

In Thailand peak transmission occurs during rainy season, from April to December. An infection can be acquired via a single bite. Humans are the main host of the virus, but non-human primates can be also infected. Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation. Vertical transmission (from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported. Other person-to-person modes of transmission, including sexual transmission, have also been reported but not confirmed.

Not long ago an Italian man was found to have the virus in his semen more than a month after he was infected in Thailand. The virus was apparently undetectable in his blood and urine after around three weeks. Spanish authorities reported the likely transmission of dengue as a consequence of sex between two men. One of the men travelled to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (both countries where dengue is endemic) and returned to Spain on September 4, 2019. He developed symptoms of dengue the next day and had unprotected sex with a partner in Spain who had not travelled outside of Spain in the previous 45 days. His partner developed dengue symptoms on September 15. Health officials say more research is needed to confirm that dengue can be transmitted sexually.

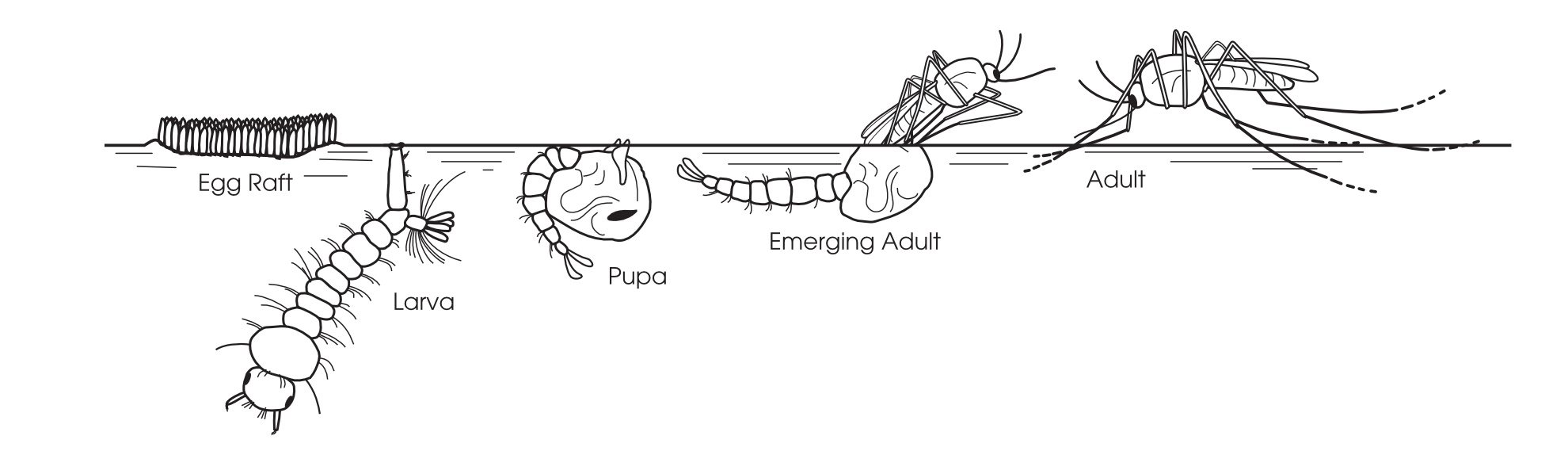

Mosquitoes have four life stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. The adult life span of Aedes aegypti can range from two weeks to a month depending on environmental conditions, and is normally completed within one and a half to three weeks. After taking a blood meal, female Aedes aegypti mosquitos produce on average 100 to 200 eggs per batch. The entire life cycle of the Aedes mosquitoes, from egg to adult, takes approximately 7-10 days.

Dengue itself is caused by a virus of the Flaviviridae family, which infects the mosquito and is transmitted to humans when they are bitten. There are four distinct but closely related serotypes of the virus that cause dengue fever: DENV1-4. The incubation time is from 3-14 days after the mosquito bites, most often within 4-7 days. Recovery from infection is believed to provide lifelong immunity against the serotype that caused the infection, but infection with another serotype may occur as cross-immunity to other serotypes after recovery is only partial, and temporary. It is therefore possible for a person to be infected four different times. Subsequent or secondary infection with a new serotype increases the risk of developing severe dengue.

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease found in tropical and sub-tropical climates worldwide, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas. As with Covid-19, there is no specific treatment, vaccine or cure for any of the three types. However, early detection of disease progression associated and access to proper medical care have lowered the fatality rate of severe dengue to below 1%.

Dengue is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected female mosquito of the species Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) or sometimes Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquito), both found throughout the world and both able to live and reproduce inside and outside of homes. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes generally prefer to live indoors and near humans, their primary food source. They like to rest in cool, shaded places such as laundry areas, in closets, under tables and in wardrobes. Dengue-carrying mosquitoes may bite at any time of day, but mostly in early morning and evening. They often bite people around the feet and ankles, and reportedly are unable to fly higher than an adult’s knees and unable to breed if the temperature falls below 16C.

In Thailand peak transmission occurs during rainy season, from April to December. An infection can be acquired via a single bite. Humans are the main host of the virus, but non-human primates can be also infected. Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation. Vertical transmission (from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported. Other person-to-person modes of transmission, including sexual transmission, have also been reported but not confirmed.

Not long ago an Italian man was found to have the virus in his semen more than a month after he was infected in Thailand. The virus was apparently undetectable in his blood and urine after around three weeks. Spanish authorities reported the likely transmission of dengue as a consequence of sex between two men. One of the men travelled to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (both countries where dengue is endemic) and returned to Spain on September 4, 2019. He developed symptoms of dengue the next day and had unprotected sex with a partner in Spain who had not travelled outside of Spain in the previous 45 days. His partner developed dengue symptoms on September 15. Health officials say more research is needed to confirm that dengue can be transmitted sexually.

Mosquitoes have four life stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. The adult life span of Aedes aegypti can range from two weeks to a month depending on environmental conditions, and is normally completed within one and a half to three weeks. After taking a blood meal, female Aedes aegypti mosquitos produce on average 100 to 200 eggs per batch. The entire life cycle of the Aedes mosquitoes, from egg to adult, takes approximately 7-10 days.

Dengue itself is caused by a virus of the Flaviviridae family, which infects the mosquito and is transmitted to humans when they are bitten. There are four distinct but closely related serotypes of the virus that cause dengue fever: DENV1-4. The incubation time is from 3-14 days after the mosquito bites, most often within 4-7 days. Recovery from infection is believed to provide lifelong immunity against the serotype that caused the infection, but infection with another serotype may occur as cross-immunity to other serotypes after recovery is only partial, and temporary. It is therefore possible for a person to be infected four different times. Subsequent or secondary infection with a new serotype increases the risk of developing severe dengue.

Three levels of illness

Illness caused by the bite of a dengue carrying mosquito is classified into three types according to severity: uncomplicated dengue fever (DF); and two potentially life threatening conditions - dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS).

DF – Symptoms of typical dengue usually start with fever up to 40C/104F or even higher after the bite of an infected mosquito, and may also include severe headache (mostly in forehead), pain behind the eyes which worsens with eye movement, severe joint and muscle pains and aches, swollen lymph nodes, nausea, general weakness, vomiting, skin rash, sudden chills, diarrhea, loss of appetite and weight loss.

DHF – Symptoms include all of the above plus pronounced damage to blood and lymph vessels, causing bleeding from the nose, gums or under skin and resulting in purplish bruises. Death is a real possibility.

DSS – Symptoms of this most severe and dangerous form of the disease include all of the symptoms of classic dengue and DHF, plus fluids leaking from blood vessels, massive bleeding and shock due to a very low blood pressure. DSS generally occurs when an infected person goes to the hospital too late and the disease has already affected vital organs. DSS is associated with high mortality, but some patients may survive provided they are admitted to an ICU where extensive treatment can be provided.

DF – Symptoms of typical dengue usually start with fever up to 40C/104F or even higher after the bite of an infected mosquito, and may also include severe headache (mostly in forehead), pain behind the eyes which worsens with eye movement, severe joint and muscle pains and aches, swollen lymph nodes, nausea, general weakness, vomiting, skin rash, sudden chills, diarrhea, loss of appetite and weight loss.

DHF – Symptoms include all of the above plus pronounced damage to blood and lymph vessels, causing bleeding from the nose, gums or under skin and resulting in purplish bruises. Death is a real possibility.

DSS – Symptoms of this most severe and dangerous form of the disease include all of the symptoms of classic dengue and DHF, plus fluids leaking from blood vessels, massive bleeding and shock due to a very low blood pressure. DSS generally occurs when an infected person goes to the hospital too late and the disease has already affected vital organs. DSS is associated with high mortality, but some patients may survive provided they are admitted to an ICU where extensive treatment can be provided.

History of dengue

The first recorded mention of symptoms compatible with dengue fever was in China during the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD), when it was referred to as a “water poison” and associated with flying insects. In the 15th to 19th centuries the primary vector, Aedes aegypti, spread out of Africa, due in part to increased transcontinental traffic secondary to the slave trade. There have been descriptions of epidemics since the 17th century. News of an epidemic in Batavia (now Jakarta) of an illness that sounds a great deal like dengue fever was reported in medical literature in 1779. Also in 1779 and 1780, an epidemic apparently swept across Africa and North America.

In 1780 US physician Benjamin Rush coined the term ‘break-bone fever’ in reference to the extreme discomfort dengue patients commonly feel in their movements due to intense joint and muscle pain.

It was confirmed in 1906 that Aedes mosquitoes are responsible for transmission, and in 1907 dengue fever was the second disease shown to be caused by a virus. (The first was yellow fever, caused by a different flavivirus.) Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the basic understanding of dengue transmission. The virus responsible for dengue fever was first isolated in 1943 by Ren Kimura and Susumu Hotta, who were studying blood samples of patients taken during the 1943 dengue epidemic in Nagasaki, Japan.

During the last part of the 20th century, many tropical regions of the world saw an increase in dengue cases, with epidemics occurring more frequently and with more severity. In recent years dengue fever has become a major international public health concern, and in a global context it is currently considered to be the most important viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that afflicts humans.

In 1780 US physician Benjamin Rush coined the term ‘break-bone fever’ in reference to the extreme discomfort dengue patients commonly feel in their movements due to intense joint and muscle pain.

It was confirmed in 1906 that Aedes mosquitoes are responsible for transmission, and in 1907 dengue fever was the second disease shown to be caused by a virus. (The first was yellow fever, caused by a different flavivirus.) Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the basic understanding of dengue transmission. The virus responsible for dengue fever was first isolated in 1943 by Ren Kimura and Susumu Hotta, who were studying blood samples of patients taken during the 1943 dengue epidemic in Nagasaki, Japan.

During the last part of the 20th century, many tropical regions of the world saw an increase in dengue cases, with epidemics occurring more frequently and with more severity. In recent years dengue fever has become a major international public health concern, and in a global context it is currently considered to be the most important viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that afflicts humans.

Dengue and Thailand

With an ideal climate for the spread of dengue, Thailand has probably witnessed epidemics going back centuries. The country’s first official cases of dengue weren’t diagnosed until 1949, however, after techniques to isolate the virus became disseminated. Since then the country has experienced several major epidemics. The first outbreak of DHF was reported in Bangkok in 1958, when 2,706 cases and 296 deaths were recorded, a fatality rate of 10.9%. The first outbreak outside Bangkok was reported in 1974 and by 1978 confirmed cases were being reported throughout the country.

A major outbreak occurred in 1987 and this remains the high-water mark for dengue fever in Thailand. In recent years the disease has demanded more attention. The dengue outbreak in 2013 was the second biggest since 1987 with regard to number of cases – a total of 154,773 infections – although the number of fatalities was relatively low at 136. This must be attributed to advancements in treatment. In 2015, 146,082 cases and 154 deaths were reported.

Dengue infections and deaths in Thailand increased sharply in 2019 (see statistics on page12) in comparison to the previous three years. Cases of dengue were reported in all of Thailand’s 77 provinces, with Chantaburi, Chiang Rai, Nakhon Ratchasima, Rayong and Ubon Ratchathani posting the highest numbers.

The Department of Disease Control (DDC) officially declared the existence of a DHF epidemic last year on June 14. The same day the MOPH announced its intention to seriously control mosquito larvae and signed an agreement to commit to that course with the Culture Ministry, Defence Ministry, Education Ministry, Interior Ministry, Tourism and Sports Ministry, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

The DDC’s Bureau of Epidemiology reported in July 2019 that most patients infected were children aged 5-14, followed by those aged 15-34. A majority of the patients who died shared similar circumstances, such as living in communities with other dengue patients, self-treatment using non-prescription medicines from local shops, and being brought to hospital too late for effective treatments or receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injections.

Sant Muangnoicharoen, a dengue specialist and doctor at the Hospital for Tropical Disease, said that children are at greater risk because they don’t take the same level of precaution as adults and, in many cases, they are unaware of the dangers. For someone over 15, the chance of death from dengue is increased with the presence of chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity and drug use. This includes ibuprofen and injections of some pain killers.

On January 21 this year the French government issued a travel warning to its citizens planning to visit Thailand due to an increase in the number of cases of dengue fever recorded since September 2019. The notice, which warned that the risk of infection was significantly higher in the Northeast of the country, particularly in Chiang Rai and Ubon Ratchathani provinces, was largely made irrelevant by the international travel restrictions imposed after the emergence of Covid-19.

At the end of May the DDC issued a national warning on dengue. According to the Bureau of Epidemiology, between January 1 and July 6 this year Thailand had recorded 25,708 cases of dengue with 15 deaths.

A major outbreak occurred in 1987 and this remains the high-water mark for dengue fever in Thailand. In recent years the disease has demanded more attention. The dengue outbreak in 2013 was the second biggest since 1987 with regard to number of cases – a total of 154,773 infections – although the number of fatalities was relatively low at 136. This must be attributed to advancements in treatment. In 2015, 146,082 cases and 154 deaths were reported.

Dengue infections and deaths in Thailand increased sharply in 2019 (see statistics on page12) in comparison to the previous three years. Cases of dengue were reported in all of Thailand’s 77 provinces, with Chantaburi, Chiang Rai, Nakhon Ratchasima, Rayong and Ubon Ratchathani posting the highest numbers.

The Department of Disease Control (DDC) officially declared the existence of a DHF epidemic last year on June 14. The same day the MOPH announced its intention to seriously control mosquito larvae and signed an agreement to commit to that course with the Culture Ministry, Defence Ministry, Education Ministry, Interior Ministry, Tourism and Sports Ministry, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

The DDC’s Bureau of Epidemiology reported in July 2019 that most patients infected were children aged 5-14, followed by those aged 15-34. A majority of the patients who died shared similar circumstances, such as living in communities with other dengue patients, self-treatment using non-prescription medicines from local shops, and being brought to hospital too late for effective treatments or receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injections.

Sant Muangnoicharoen, a dengue specialist and doctor at the Hospital for Tropical Disease, said that children are at greater risk because they don’t take the same level of precaution as adults and, in many cases, they are unaware of the dangers. For someone over 15, the chance of death from dengue is increased with the presence of chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity and drug use. This includes ibuprofen and injections of some pain killers.

On January 21 this year the French government issued a travel warning to its citizens planning to visit Thailand due to an increase in the number of cases of dengue fever recorded since September 2019. The notice, which warned that the risk of infection was significantly higher in the Northeast of the country, particularly in Chiang Rai and Ubon Ratchathani provinces, was largely made irrelevant by the international travel restrictions imposed after the emergence of Covid-19.

At the end of May the DDC issued a national warning on dengue. According to the Bureau of Epidemiology, between January 1 and July 6 this year Thailand had recorded 25,708 cases of dengue with 15 deaths.

Waiting for a cure

Although for decades considerable efforts have been made toward developing a dengue vaccine, no truly effective vaccine currently exists. In 2016 a much-anticipated vaccine became available in parts of Southeast Asia and Central and South America. People in Thailand were excited when the vaccine arrived with a promise of 93% efficacy in reducing severity of the disease and 80% effectiveness in lessening the need for hospital treatment.

Problems with the new vaccine soon became apparent, however. The three-installment dose was priced at around US$207, a bit expensive for most Thais. In 2017 a study presented evidence that the vaccine could backfire on those who had never had the virus before and lead to a more serious infection. In 2018 the vaccine’s manufacturers confirmed that it should only be given to those who had previously contracted a dengue infection, as it might increase the severity of subsequent infections. Finally, the vaccination has proved to be only around 60% effective, leaving researchers still searching for a dengue vaccination that is more effective, affordable and safe.

Problems with the new vaccine soon became apparent, however. The three-installment dose was priced at around US$207, a bit expensive for most Thais. In 2017 a study presented evidence that the vaccine could backfire on those who had never had the virus before and lead to a more serious infection. In 2018 the vaccine’s manufacturers confirmed that it should only be given to those who had previously contracted a dengue infection, as it might increase the severity of subsequent infections. Finally, the vaccination has proved to be only around 60% effective, leaving researchers still searching for a dengue vaccination that is more effective, affordable and safe.

Medical intervention needed

People who suspect they may be suffering symptoms of dengue fever should see a doctor at once. There’s no specific medication to kill the virus, but there’s no doubt that medical intervention saves lives. For severe dengue symptoms, including shock and coma, early and aggressive emergency treatment with fluids and electrolyte replacement can be life-saving. One treatment involves the intravenous administration of blood platelets.

Most people with uncomplicated dengue recover completely within about two weeks, but others may go through several weeks to months of feeling tired and/or depressed. Some victims say they experience lingering effects many years after infection. To speed recovery, healthcare experts recommend getting plenty of bed rest, drinking lots of fluids and taking medicine to reduce fever, although some doctors advise against taking aspirin.

The mosquitoes that transmit the dengue virus often breed in used automobile tires, flower pots, old oil drums and other man-made containers like earthenware jars, metal drums, concrete cisterns and discarded plastic containers. It is vital to eliminate these breeding sources from public and private property.

To prevent being bitten, avoid areas with standing water, and wear long-sleeve shirts and long trousers or dresses in neutral colors that cover limbs and neck during daylight hours when the mosquitoes are most active. Secure windows and doors and check for holes in screens and consider sleeping under a mosquito net. Other suggested preventive measures include the use of coils, electric vapour mats and mosquito repellant sprays containing DEET.

Most people with uncomplicated dengue recover completely within about two weeks, but others may go through several weeks to months of feeling tired and/or depressed. Some victims say they experience lingering effects many years after infection. To speed recovery, healthcare experts recommend getting plenty of bed rest, drinking lots of fluids and taking medicine to reduce fever, although some doctors advise against taking aspirin.

The mosquitoes that transmit the dengue virus often breed in used automobile tires, flower pots, old oil drums and other man-made containers like earthenware jars, metal drums, concrete cisterns and discarded plastic containers. It is vital to eliminate these breeding sources from public and private property.

To prevent being bitten, avoid areas with standing water, and wear long-sleeve shirts and long trousers or dresses in neutral colors that cover limbs and neck during daylight hours when the mosquitoes are most active. Secure windows and doors and check for holes in screens and consider sleeping under a mosquito net. Other suggested preventive measures include the use of coils, electric vapour mats and mosquito repellant sprays containing DEET.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed