Backed by more than a thousand staff, Dr Sirilaksana Khoman is leading the charge against corruption involving state officials and government contracts

By Maxmilian Wechsler

By Maxmilian Wechsler

| CONTRARY to what some people believe, corruption wasn’t unleashed here by Thaksin Shinawatra. As in other nations, it’s been around for a long time. However, it is now a much bigger problem and more blatant than in the past, according to one of Thailand’s major corruption-busters. It’s also more complex, with different types of corruption emerging in recent years, says Dr Sirilaksana Khoman, senior academic consultant and chair of Economic Sector Corruption Prevention at the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), an independent organization with considerable powers, whose remit covers the all-important government sector. Dr Sirilaksana believes the ‘new’ type of corruption now seen in Thailand can be traced back to 1997, when the country faced a raft of previously unknown challenges, including the Asian economic crisis, the concentration of political power under a “charismatic” new leader and numerous allegations of large scale corruption. Ironically, 1997 also saw an increase in the number of organizations intended to deal with corruption. |

“Corruption exists in every country and has for a long, long time, even in European nations. In the old days if you had someone in authority and they were able to hand out favours like an appointment to a high position, people would come with gifts,” she says.

“In Thailand, too, corruption has always been going on, but I want to use 1997 as a cut-off point, because the types of corruption that occurred before and after 1997 are very different.

“Before 1997 it was mostly about petty bribery of officials, or straightforward kickbacks from projects. Some petty bribery is still going on, but people are reluctant to report it. We do feel that the incidence of petty bribery has declined through civil service reform and the use of technology, sometimes just simple technology such as cameras at intersections that reduce contact between the authorities and the citizens.

“Police and motorists have less personal contact now and that reduces the opportunity for corruption. Many government agencies have embraced the use of technology and streamlined bureaucracy and we believe that has reduced corruption for the Thai people.

“Foreigners might not know this, but to get a Thai ID used to take a whole day. People had an incentive to offer a bribe in order to get an ID in an hour – the same with passports. You use to spend at least a half day waiting in the passport office, but now it takes only five minutes. This reduces the opportunity for corruption.

Since joining the NACC in 2007, Dr Sirilaksana has been involved in a number of what she calls “grand” corruption cases, including the 4,000 NGV buses ordered by the Bangkok Metropolitan Transport Authority (the project was shelved following NACC recommendation); and the bribery case involving a former governor of the Tourist Authority of Thailand who gave a lucrative contract to an American couple to organize the Bangkok International Film Festivals.

She’s also investigated the issue of CTX X-ray baggage machines for Suvarnabhumi airport, acquired with alleged kickbacks to Thai officials by the US manufacturer; the Klong Dan wastewater treatment project land acquisition scandal; and the alleged bribe offered by a US cigarette company to Thai Tobacco Monopoly officials.

In a paper titled “Corruption, Transactions Costs and Network Relationships: Governance Challenges for Thailand,” she provides details on large road projects with a table of contract winners and their political affiliations. All of the top ten road projects from fiscal years 2007-2011 went to companies known to have political affiliations or that had made large overt campaign contributions to political candidates and various parties. The contracts involved some large amounts of money, ranging from almost 700 million baht to 19.7 billion baht.

Dr Sirilksana’s family name is well known in Thailand because of her father-in-law, Dr Thanat Khoman, who was foreign minister from 1959-1971, chairman of the Democrat Party between 1979-1982 and deputy prime minister from 1980-1982. He was also a prime mover in the formation of ASEAN in 1967 when the inaugural meeting was held in Bangkok.

Dr Sirilaksana was teaching at Thammasat University when first approached to join NACC. She was initially hesitant to accept a post because she had never worked outside of academia. “I liked being in the university system where you have a lot of freedom to criticize and to suggest policy. But when I was invited to join the commission, I felt that it would be interesting since I had been involved in research on public policy in various areas of international trade, education and health.

“My job as senior academic consultant is unique in the organization. I oversee the research centre because of my academic background. I feel that to fight or prevent corruption, we need to have a body of knowledge defining the various types of corruption, how they occur and the areas of vulnerability. We need research for that. I am sometimes involved in the suppression side, but my job is mainly in prevention.

“I look at cases that involve large government projects, such as the 350 billion baht water management project and the two trillion baht transport infrastructure project. I am also vice-chair of the watchdog subcommittee that brings together both public and private sector experts to scrutinize large projects.

“We are now doing a sort of pre-emptive work, following and monitoring projects right from their inception, and hopefully intercept projects that are non-transparent, or help to improve their procedures.

“This is something new at the NACC. As an economist, I feel that’s where my contribution lies, in monitoring economic policy and procedures, as well as rules and regulations that provide loopholes or opportunities for corruption to occur.

“We should not wait for corruption to happen, because the investigation necessarily takes a long time. So we monitor big projects like the Suvarnabhumi airport extension Phase II or the NGV buses, as they unfold.

“Once the government approves a big project, we will set up a team and recruit knowledgeable people from outside the organization to help. Our staff is very competent but when we monitor large projects we need expertise in various areas, so we recruit people like engineers experienced, for example, in the field of water resources. These are ad hoc committees that monitor government projects.

“We have about 1,200 people in our organization but we have actually 1,800 positions. We cannot fill them all right now because our budget has been cut by 60 percent this year,” says Dr Sirilaksana. At this point she says the NACC needs “a different way of funding.

“We are independent in every way but the budget still comes from the government and the Parliament, so if we have a hostile Parliament, our budget is in jeopardy.”

“In Thailand, too, corruption has always been going on, but I want to use 1997 as a cut-off point, because the types of corruption that occurred before and after 1997 are very different.

“Before 1997 it was mostly about petty bribery of officials, or straightforward kickbacks from projects. Some petty bribery is still going on, but people are reluctant to report it. We do feel that the incidence of petty bribery has declined through civil service reform and the use of technology, sometimes just simple technology such as cameras at intersections that reduce contact between the authorities and the citizens.

“Police and motorists have less personal contact now and that reduces the opportunity for corruption. Many government agencies have embraced the use of technology and streamlined bureaucracy and we believe that has reduced corruption for the Thai people.

“Foreigners might not know this, but to get a Thai ID used to take a whole day. People had an incentive to offer a bribe in order to get an ID in an hour – the same with passports. You use to spend at least a half day waiting in the passport office, but now it takes only five minutes. This reduces the opportunity for corruption.

Since joining the NACC in 2007, Dr Sirilaksana has been involved in a number of what she calls “grand” corruption cases, including the 4,000 NGV buses ordered by the Bangkok Metropolitan Transport Authority (the project was shelved following NACC recommendation); and the bribery case involving a former governor of the Tourist Authority of Thailand who gave a lucrative contract to an American couple to organize the Bangkok International Film Festivals.

She’s also investigated the issue of CTX X-ray baggage machines for Suvarnabhumi airport, acquired with alleged kickbacks to Thai officials by the US manufacturer; the Klong Dan wastewater treatment project land acquisition scandal; and the alleged bribe offered by a US cigarette company to Thai Tobacco Monopoly officials.

In a paper titled “Corruption, Transactions Costs and Network Relationships: Governance Challenges for Thailand,” she provides details on large road projects with a table of contract winners and their political affiliations. All of the top ten road projects from fiscal years 2007-2011 went to companies known to have political affiliations or that had made large overt campaign contributions to political candidates and various parties. The contracts involved some large amounts of money, ranging from almost 700 million baht to 19.7 billion baht.

Dr Sirilksana’s family name is well known in Thailand because of her father-in-law, Dr Thanat Khoman, who was foreign minister from 1959-1971, chairman of the Democrat Party between 1979-1982 and deputy prime minister from 1980-1982. He was also a prime mover in the formation of ASEAN in 1967 when the inaugural meeting was held in Bangkok.

Dr Sirilaksana was teaching at Thammasat University when first approached to join NACC. She was initially hesitant to accept a post because she had never worked outside of academia. “I liked being in the university system where you have a lot of freedom to criticize and to suggest policy. But when I was invited to join the commission, I felt that it would be interesting since I had been involved in research on public policy in various areas of international trade, education and health.

“My job as senior academic consultant is unique in the organization. I oversee the research centre because of my academic background. I feel that to fight or prevent corruption, we need to have a body of knowledge defining the various types of corruption, how they occur and the areas of vulnerability. We need research for that. I am sometimes involved in the suppression side, but my job is mainly in prevention.

“I look at cases that involve large government projects, such as the 350 billion baht water management project and the two trillion baht transport infrastructure project. I am also vice-chair of the watchdog subcommittee that brings together both public and private sector experts to scrutinize large projects.

“We are now doing a sort of pre-emptive work, following and monitoring projects right from their inception, and hopefully intercept projects that are non-transparent, or help to improve their procedures.

“This is something new at the NACC. As an economist, I feel that’s where my contribution lies, in monitoring economic policy and procedures, as well as rules and regulations that provide loopholes or opportunities for corruption to occur.

“We should not wait for corruption to happen, because the investigation necessarily takes a long time. So we monitor big projects like the Suvarnabhumi airport extension Phase II or the NGV buses, as they unfold.

“Once the government approves a big project, we will set up a team and recruit knowledgeable people from outside the organization to help. Our staff is very competent but when we monitor large projects we need expertise in various areas, so we recruit people like engineers experienced, for example, in the field of water resources. These are ad hoc committees that monitor government projects.

“We have about 1,200 people in our organization but we have actually 1,800 positions. We cannot fill them all right now because our budget has been cut by 60 percent this year,” says Dr Sirilaksana. At this point she says the NACC needs “a different way of funding.

“We are independent in every way but the budget still comes from the government and the Parliament, so if we have a hostile Parliament, our budget is in jeopardy.”

Defining corruption

In her view there are 10 different kinds of corruption, ranging from the very common sort that entails shirking on the job – spending time that one is supposed to be working in talking to friends or having a snack, for example.

“I feel this is corruption because you are stealing time. Corruption ranges from this most simple form to the abuse of power, like approving various permits for personal profit up to ‘grand corruption,’ where policy is formulated with certain people in mind as beneficiaries – perhaps friends and family. It is necessary to classify the different kinds of corruption as the different measures are required to deal with each type of corruption.

“At this moment the NACC covers only the government sector, with all government officials being under its jurisdiction. If one company is defrauding another one, this lies beyond the scope of the NACC’s powers, but if they pay a bribe to a government official then it becomes NACC’s business.

“According to the law, government officials like me can accept no gifts or favours, no lunch or anything else except for special occasions or reasons, and then the value cannot exceed 3,000 baht. This would apply to a friend who assumes a new position and you treat him for lunch.

“The NACC has jurisdiction over two Acts, namely the Organic Act on Counter Corruption B.E. 2542 (1999) and the Act Concerning Offences Related to the Submission of Bids to Government Agencies B.E. 2542 (1999), or what we call the ‘Collusion Act.’ If private companies are bidding for contracts and they collude or do something which is irregular they will be under investigation as well. In fact, this is the law that was recently used to get the major conviction of a minister in the Thaksin government, in the case of Austrian-made Steyr fire trucks and firefighting boats. We convicted the minister using the Collusion Act.”

She explains that the NAAC conducts an investigation then sends its findings to the Office of the Attorney General (OAG). If the OAG doesn’t think there is enough evidence for prosecution and the NAAC does, they set up a joint committee. “If the joint committee still cannot agree then we will prosecute ourselves, and this was the case with the fire trucks. By the way, the case is still going on. We are trying to get cooperation from the Austrian side. Somebody in their company definitely bribed someone.”

1997 was pivotal year

Has Dr Sirilaksana had personal experience of corruption? “I guess I haven’t personally encountered it much. Once I was stopped by the traffic police, and the officer just stood there presumably waiting for me to make an offer… I told him ‘please give me a ticket.’ He told me to go.

“In the past, when I was at university, someone tried to bribe me to get his son into our program. We were accepting 70 students but more than 1,000 applied. The man who tried to bribe me is a very prominent politician. When I refused he threatened go to the president of the university. I told him to go ahead, since it would make no difference.

“I think we are reducing petty corruption, but what concerns me is the large scale corruption like the Austrian fire trucks, the Klong Dan wastewater treatment project, Suvarnabhumi airport Phase I and so many other cases still pending with the NACC. These cases involve a network of strategically placed people, and have strengthened since 1997.”

During that year, Thailand witnessed a number of events that caused an upsurge in corruption, the doctor believes. “For one, the Constitution that was promulgated in that year laid the groundwork for strong government. The Constitution actually had all the underpinnings for good governance and good government with checks and balances and inclusive people’s participation, rights and liberty. But that year also coincided with the Asian economic crisis, which started with the financial crisis in Thailand. Private-sector banks were decimated, and government banks assumed greater prominence, and became tools for government policy more than they had been in the past.

“A charismatic leader was elected and served under the new Constitution for the first time, and there was a structural shift in economic power from the banking sector to the telecommunications sector. At the same time, civil service reform was in full swing, allowing the creation of public organizations that had greater flexibility in their budgetary and administrative processes. Decentralization, both administrative and budgetary, was seen as a move that would empower citizens to make government agencies more accountable and responsive to local needs.

“But ironically this led to a concentration of political power. Many allegations of large scale corruption emerged during this period. On the other hand, the 1997 constitution also had provisions for the creation of independent organizations, including the NACC and the Auditor General which are intended to deal with corruption, as well as agencies like the Human Rights Commission.

“The NACC was actually established in 1999 because there first had to be laws enacted for the creation of the agency,” Dr Sirilaksana explains, adding that the NACC reports to the Senate, which is also chiefly responsible for appointing its commissioners.

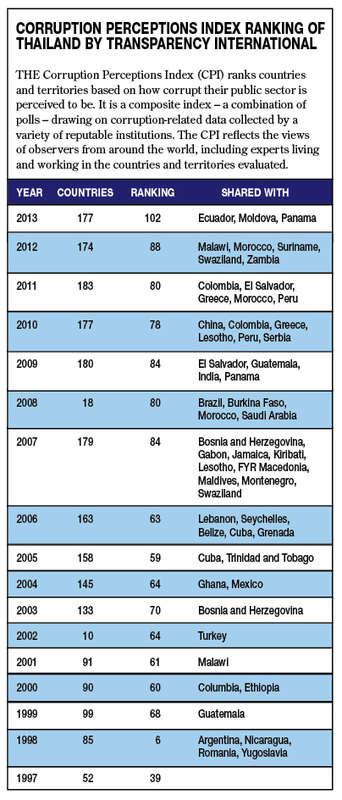

Corruption index

Thailand’s ranking of 102 in 2013 by Transparency International (see sidebar) is only a perceptions index, she says, but it is useful in making people aware and concerned. “I am not complaining about their findings but it’s important to remember that most of those they interview are foreign business people and the Thai people they encounter may not be able to communicate well with them, and this may cause frustration and affect the ‘ease of doing business.’

“For the last two years the NACC has constructed an evidence-based Transparency Index to evaluate all government agencies at the department level. There are actually 11 indexes, one of them on procurement which gives marks for proper procedures and transparency in procurement. We ask the question: Do you announce the yearly plan for the bidding for projects? Departments that say they do have to provide evidence like the screen capture of a website.

“There are certain things we know most departments don’t do which we use as criteria, so they will be encouraged to do these things if they want good marks from us. For example, we ask: At the end of the year, do you conduct an assessment of procurement for the past year, like report on what percentage of procurement projects are conducted through open bidding, or through special methods? We don’t judge what percentage should be ideal for their department, simply whether an assessment is done. The Health Department of the Ministry of Public Health came in on top of the survey both years.

In her view there are 10 different kinds of corruption, ranging from the very common sort that entails shirking on the job – spending time that one is supposed to be working in talking to friends or having a snack, for example.

“I feel this is corruption because you are stealing time. Corruption ranges from this most simple form to the abuse of power, like approving various permits for personal profit up to ‘grand corruption,’ where policy is formulated with certain people in mind as beneficiaries – perhaps friends and family. It is necessary to classify the different kinds of corruption as the different measures are required to deal with each type of corruption.

“At this moment the NACC covers only the government sector, with all government officials being under its jurisdiction. If one company is defrauding another one, this lies beyond the scope of the NACC’s powers, but if they pay a bribe to a government official then it becomes NACC’s business.

“According to the law, government officials like me can accept no gifts or favours, no lunch or anything else except for special occasions or reasons, and then the value cannot exceed 3,000 baht. This would apply to a friend who assumes a new position and you treat him for lunch.

“The NACC has jurisdiction over two Acts, namely the Organic Act on Counter Corruption B.E. 2542 (1999) and the Act Concerning Offences Related to the Submission of Bids to Government Agencies B.E. 2542 (1999), or what we call the ‘Collusion Act.’ If private companies are bidding for contracts and they collude or do something which is irregular they will be under investigation as well. In fact, this is the law that was recently used to get the major conviction of a minister in the Thaksin government, in the case of Austrian-made Steyr fire trucks and firefighting boats. We convicted the minister using the Collusion Act.”

She explains that the NAAC conducts an investigation then sends its findings to the Office of the Attorney General (OAG). If the OAG doesn’t think there is enough evidence for prosecution and the NAAC does, they set up a joint committee. “If the joint committee still cannot agree then we will prosecute ourselves, and this was the case with the fire trucks. By the way, the case is still going on. We are trying to get cooperation from the Austrian side. Somebody in their company definitely bribed someone.”

1997 was pivotal year

Has Dr Sirilaksana had personal experience of corruption? “I guess I haven’t personally encountered it much. Once I was stopped by the traffic police, and the officer just stood there presumably waiting for me to make an offer… I told him ‘please give me a ticket.’ He told me to go.

“In the past, when I was at university, someone tried to bribe me to get his son into our program. We were accepting 70 students but more than 1,000 applied. The man who tried to bribe me is a very prominent politician. When I refused he threatened go to the president of the university. I told him to go ahead, since it would make no difference.

“I think we are reducing petty corruption, but what concerns me is the large scale corruption like the Austrian fire trucks, the Klong Dan wastewater treatment project, Suvarnabhumi airport Phase I and so many other cases still pending with the NACC. These cases involve a network of strategically placed people, and have strengthened since 1997.”

During that year, Thailand witnessed a number of events that caused an upsurge in corruption, the doctor believes. “For one, the Constitution that was promulgated in that year laid the groundwork for strong government. The Constitution actually had all the underpinnings for good governance and good government with checks and balances and inclusive people’s participation, rights and liberty. But that year also coincided with the Asian economic crisis, which started with the financial crisis in Thailand. Private-sector banks were decimated, and government banks assumed greater prominence, and became tools for government policy more than they had been in the past.

“A charismatic leader was elected and served under the new Constitution for the first time, and there was a structural shift in economic power from the banking sector to the telecommunications sector. At the same time, civil service reform was in full swing, allowing the creation of public organizations that had greater flexibility in their budgetary and administrative processes. Decentralization, both administrative and budgetary, was seen as a move that would empower citizens to make government agencies more accountable and responsive to local needs.

“But ironically this led to a concentration of political power. Many allegations of large scale corruption emerged during this period. On the other hand, the 1997 constitution also had provisions for the creation of independent organizations, including the NACC and the Auditor General which are intended to deal with corruption, as well as agencies like the Human Rights Commission.

“The NACC was actually established in 1999 because there first had to be laws enacted for the creation of the agency,” Dr Sirilaksana explains, adding that the NACC reports to the Senate, which is also chiefly responsible for appointing its commissioners.

Corruption index

Thailand’s ranking of 102 in 2013 by Transparency International (see sidebar) is only a perceptions index, she says, but it is useful in making people aware and concerned. “I am not complaining about their findings but it’s important to remember that most of those they interview are foreign business people and the Thai people they encounter may not be able to communicate well with them, and this may cause frustration and affect the ‘ease of doing business.’

“For the last two years the NACC has constructed an evidence-based Transparency Index to evaluate all government agencies at the department level. There are actually 11 indexes, one of them on procurement which gives marks for proper procedures and transparency in procurement. We ask the question: Do you announce the yearly plan for the bidding for projects? Departments that say they do have to provide evidence like the screen capture of a website.

“There are certain things we know most departments don’t do which we use as criteria, so they will be encouraged to do these things if they want good marks from us. For example, we ask: At the end of the year, do you conduct an assessment of procurement for the past year, like report on what percentage of procurement projects are conducted through open bidding, or through special methods? We don’t judge what percentage should be ideal for their department, simply whether an assessment is done. The Health Department of the Ministry of Public Health came in on top of the survey both years.

| Eyes on assets “One thing we are doing more aggressively now is requiring a larger number of high-ranking government officials to declare their assets and liabilities, and using this provision in the law more aggressively,” says Dr Sirilaksana. “There was a case last year involving the Transport Ministry permanent secretary. Some burglars broke into his house and they found a lot of cash he had not declared. The burglars were later caught and the money confiscated. In such cases the burden of proof is on their side, to explain the source of income or wealth. In corruption cases we have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that malfeasance occurred, but in this case the permanent secretary had to give proof of where the money came from since he hadn’t declared it. He said he had only five million baht and it had something to do with a wedding. But the burglars took 19 million baht. This is what the police counted. The burglars had no reason to lie. “Our finding was that that he didn’t declare his assets, so he was removed from office and 64 million baht was ordered seized. The corruption case is still pending but at least he was removed quickly. This is a civil case. Several MPs for example in Chiang Mai and elsewhere have been removed from office.” Filling in the loopholes “Thai anti-corruption laws are strong but there are some areas where there are loopholes. Just last year we amended the law with respect to removal from office. Three or four years ago one minister was removed from office and a month later he was appointed to another ministry; the law didn’t specifically prohibit it. That’s why we had to change the law to say that if you are removed from office you can’t take a new position for five years. “Also just over a year ago, we amended other clauses in the law, including the statute of limitations because in the past some people would flee the country and wait until the statute of limitations run out, and then return. Now, under the newly amended Anti-Corruption Law (the Organic Act on Counter Corruption B.E. 2542 (amended B.E. 2554) which is under the NACC jurisdiction rather than the Criminal Code (which has a broader coverage and is beyond our scope), the statute of limitations for corruption cases will stop if the accused flees during our investigation and will start to count again if the accused returns. |

“The NACC also recently amended the Anti-Corruption Law to allow us to closely monitor large procurement projects, and require procuring agencies to publish and explain how the reference prices are calculated, and file a separate tax return with the Revenue Department for each large project. Whistle-blowing protection has also been introduced, as well as witness protection. The NACC is also now empowered to use the provisions of the Anti-Money Laundering Act in pursuant of corruption cases.”

Officials and corruption

Asked whether government officials like police officers have a case when they claim they have to take bribes because their salaries are low, she replies: “Yes and no. The system at the Royal Thai Police (RTP) is problematic. One of our commissioners had a bomb thrown into his home and a young policeman came to collect the evidence and he said that when he joined the RTP he didn’t even have a chair or desk and had to buy them himself. He also had to buy a gun, handcuffs, a motorcycle and other items.

“The RTP is almost sending a signal to newly recruited policemen to ‘go out there and earn your own living on the street’. There’s something wrong here. The RTP’s budget should not be inadequate, but where does the money go?

“On the other hand, some people say that if people are paid a lot of money then they won’t be corrupt, but I see a lot of people who have a small salary and they are content and not corrupt. Many people I know in their late 20s have families that they have to look after, they go to work by bus and live frugally but with dignity and they don’t live beyond their means. Then you look at the really corrupt people, who are often billionaires. So having money doesn’t prevent corruption,” Dr Sirilaksana said.

“Corruption in Thailand can be reduced if we have the cooperation of every sector of society, keeping watch on big projects and informing us. Remember, the business sector is where the illicit payment is coming from. If there’s no bribe giver there’s no bribe taker. I would be very happy to be out of this job. If we can get the cooperation of everyone, especially business people, we can tackle this problem. There are some promising signs that the business sector is coming on board. I believe that we can accomplish good things together,” Dr Khoman said.

“The Thai Chamber of Commerce now has some 400 members who are engaged in a collective action against corruption. They signed an integrity pact guaranteeing that they will not pay bribes.”

Advice to foreigners

“Foreigners who are asked or forced to pay bribes should report to us directly. Now we have a whistle-blower program and witness protection under the amended law of 2012. In fact, if you know about any corruption and have evidence, please give it to us. Everyone knows it happens, but we can’t work on the basis of hearsay or rumour. We need hard evidence. Take a photo or record something, which is very easy these days. And don’t pay bribes.

“If someone wants to complain about corruption to the NACC, they can send us a letter. They should sign it in their name but can request to remain anonymous. The system is very good. Only one or two people are allowed to open such letters – I don’t even know who they are. What they are told to do is to cut out the name, put it in an envelope, seal it and place it in the safe. Even a judge cannot order the opening of the envelope. People shouldn’t be afraid and they should come forward. We receive many complaints every day. Of course, the process may be a bit slow, since we have to weed out untruths, but we’ll do our best.”

Officials and corruption

Asked whether government officials like police officers have a case when they claim they have to take bribes because their salaries are low, she replies: “Yes and no. The system at the Royal Thai Police (RTP) is problematic. One of our commissioners had a bomb thrown into his home and a young policeman came to collect the evidence and he said that when he joined the RTP he didn’t even have a chair or desk and had to buy them himself. He also had to buy a gun, handcuffs, a motorcycle and other items.

“The RTP is almost sending a signal to newly recruited policemen to ‘go out there and earn your own living on the street’. There’s something wrong here. The RTP’s budget should not be inadequate, but where does the money go?

“On the other hand, some people say that if people are paid a lot of money then they won’t be corrupt, but I see a lot of people who have a small salary and they are content and not corrupt. Many people I know in their late 20s have families that they have to look after, they go to work by bus and live frugally but with dignity and they don’t live beyond their means. Then you look at the really corrupt people, who are often billionaires. So having money doesn’t prevent corruption,” Dr Sirilaksana said.

“Corruption in Thailand can be reduced if we have the cooperation of every sector of society, keeping watch on big projects and informing us. Remember, the business sector is where the illicit payment is coming from. If there’s no bribe giver there’s no bribe taker. I would be very happy to be out of this job. If we can get the cooperation of everyone, especially business people, we can tackle this problem. There are some promising signs that the business sector is coming on board. I believe that we can accomplish good things together,” Dr Khoman said.

“The Thai Chamber of Commerce now has some 400 members who are engaged in a collective action against corruption. They signed an integrity pact guaranteeing that they will not pay bribes.”

Advice to foreigners

“Foreigners who are asked or forced to pay bribes should report to us directly. Now we have a whistle-blower program and witness protection under the amended law of 2012. In fact, if you know about any corruption and have evidence, please give it to us. Everyone knows it happens, but we can’t work on the basis of hearsay or rumour. We need hard evidence. Take a photo or record something, which is very easy these days. And don’t pay bribes.

“If someone wants to complain about corruption to the NACC, they can send us a letter. They should sign it in their name but can request to remain anonymous. The system is very good. Only one or two people are allowed to open such letters – I don’t even know who they are. What they are told to do is to cut out the name, put it in an envelope, seal it and place it in the safe. Even a judge cannot order the opening of the envelope. People shouldn’t be afraid and they should come forward. We receive many complaints every day. Of course, the process may be a bit slow, since we have to weed out untruths, but we’ll do our best.”

| DR SIRILAKSANA IN FOCUS DR Sirilaksana Khoman was born in Bangkok. Her mother was a teacher and her father a diplomat, his last post being ambassador to Japan. Before joining the NACC in 2007, Dr Sirilaksana was dean of the Faculty of Economics at Thammasat University. She received her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Economics from the Australian National University, a PhD in Economics from the University of Hawaii, and a Certificate in International Trade Regulation from Harvard Law School. Dr Sirilaksana has done extensive work for several international organizations, including the World Bank, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and the Asian Development Bank. She has taught at the Australian National University, the United Nations University in Tokyo and as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Oregon, USA. Currently she is on the Global Agenda Council on Anti-Corruption and Transparent, World Economic Forum. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed