| Hundreds of deaths and injuries caused by an industrial fire in a building with poor safety standards, recalls Maxmilian Wechsler NINETEEN ninety-three was an eventful year in Thailand, with visits by Nobel Peace Prize laureates Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama and a concert by pop superstar Michael Jackson. The first Thai broadcasting satellite was launched in Guiana and a controversial new law requiring motorcyclists and their passengers to wear crash helmets came into effect. But for many, 1993 will be remembered as a year of tragedy. The collapse of the Royal Plaza Hotel in Nakhon Ratchasima province in August killed 127 people and seriously injured hundreds more, but that didn’t top the list of man-made, avoidable catastrophes. That grim distinction belongs to the May 10 Kader toy factory fire in Nakhon Pathom, which according to the official report left 188 workers dead and almost 500 injured. It was the worst industrial disaster in Thai history. The workers at Kader were mostly young women from poor rural families living in nearby villages. According to some survivors, they were told the fire was minor and that they should continue working. The fire started in Building One and spread to Buildings Two and Three. Because the fire started shortly before the shifts were changing there were many more workers present and many more casualties. |

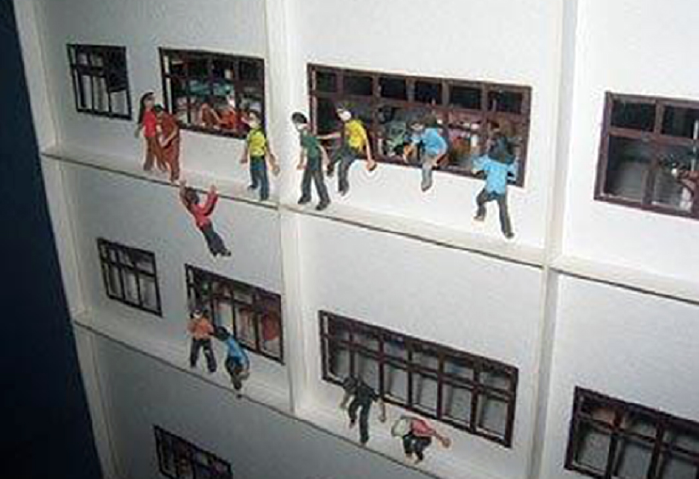

Fire investigators found that ground floor emergency exit doors in Building One were locked, apparently to prevent theft. The stairwells collapsed soon after the fire started, leaving hundreds of workers on the second, third, and fourth floors with no choice but to make a perilous jump from windows to escape the heavy smoke and flames. Many of them didn’t survive the fall or were badly injured.

According to emergency crews, bodies were piled up in narrow corridors leading to the exits, near the locked doors or underneath the collapsed staircases in Building One. Many of these workers died from smoke inhalation.

Officially 188 workers, 174 women and 14 men, died and another 469 were injured. However, The New York Times reported on May 13: “An Interior Ministry spokesman told reporters Tuesday night that the death toll had reached 213, while a local television station reported a count of 240.”

Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai arrived at the scene of the disaster in the evening of May 10. According to press reports, he asked a provincial engineer who was also at the scene: “How could you let this happen? You allow them to run a factory like this without inspection.” The engineer reportedly had no answer.

A police inspector told PM Chuan that initial investigation showed one of the factory exit doors had been locked, and an assistant police chief described the buildings as ‘obviously sub- standard’. The PM pledged that the government would urgently address fire safety issues. Late Thai Industry Minister Sanan Kachornprasart said: “Those factories without a fire prevention system will be ordered to install one, or we will shut them down.”

The Kader fire and the abysmal safety practices in place were the big story in Thai tabloids and TV news broadcasts for weeks, and it also generated a lot of interest from foreign media and international organisations. The International Labor Organization (ILO), the National Fire Protection Association and the now-defunct International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) assigned staff to compile reports on the tragedy and campaigned for higher fire safety standards and compensation for victims and their families.

The publicity and the public outcry helped to hold the government to its promises, resulting in regulations that stipulated improvements in the design and construction of factories and more stringent fire safety measures and enforcement policies. It probably goes without saying that these regulations are not always met with compliance.

According to emergency crews, bodies were piled up in narrow corridors leading to the exits, near the locked doors or underneath the collapsed staircases in Building One. Many of these workers died from smoke inhalation.

Officially 188 workers, 174 women and 14 men, died and another 469 were injured. However, The New York Times reported on May 13: “An Interior Ministry spokesman told reporters Tuesday night that the death toll had reached 213, while a local television station reported a count of 240.”

Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai arrived at the scene of the disaster in the evening of May 10. According to press reports, he asked a provincial engineer who was also at the scene: “How could you let this happen? You allow them to run a factory like this without inspection.” The engineer reportedly had no answer.

A police inspector told PM Chuan that initial investigation showed one of the factory exit doors had been locked, and an assistant police chief described the buildings as ‘obviously sub- standard’. The PM pledged that the government would urgently address fire safety issues. Late Thai Industry Minister Sanan Kachornprasart said: “Those factories without a fire prevention system will be ordered to install one, or we will shut them down.”

The Kader fire and the abysmal safety practices in place were the big story in Thai tabloids and TV news broadcasts for weeks, and it also generated a lot of interest from foreign media and international organisations. The International Labor Organization (ILO), the National Fire Protection Association and the now-defunct International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) assigned staff to compile reports on the tragedy and campaigned for higher fire safety standards and compensation for victims and their families.

The publicity and the public outcry helped to hold the government to its promises, resulting in regulations that stipulated improvements in the design and construction of factories and more stringent fire safety measures and enforcement policies. It probably goes without saying that these regulations are not always met with compliance.

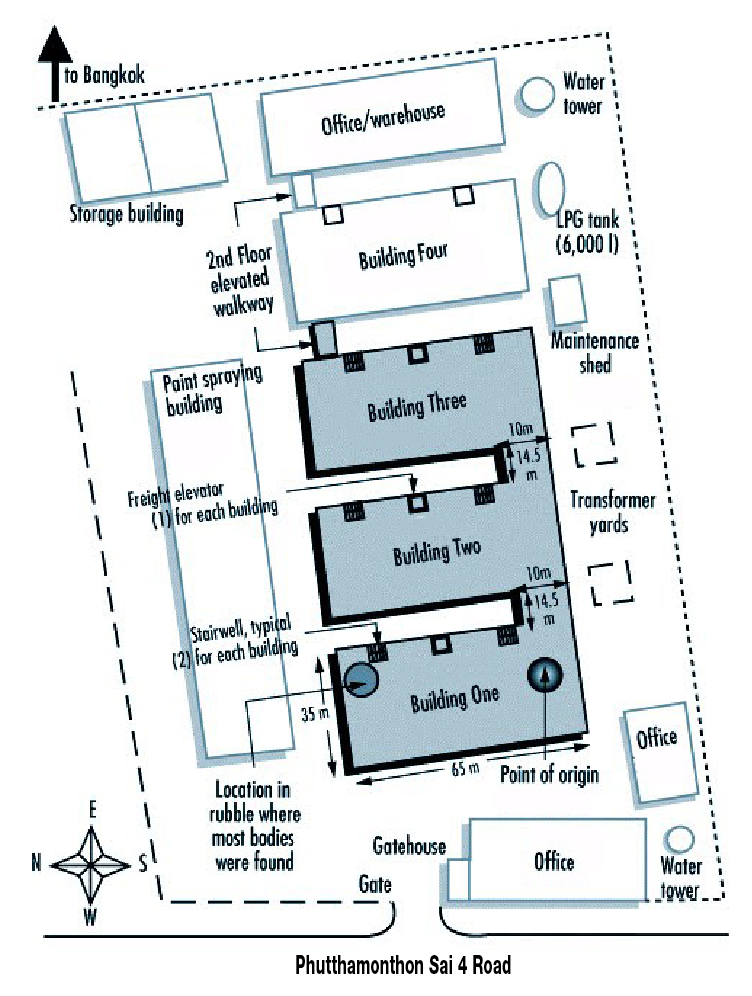

| Fire and rescue operation At around 4pm on Monday, May 10, 1993, a small fire started on the first floor of Building One, part of the E-shaped structure that included Buildings Two and Three of the Kader toy factory on Phuttamonthon Sai 4 Road in Nakhon Pathom’s Sam Phran district. The part of the building where the fire started was used to package and store the finished products. Other parts of the factory contained raw materials, which were also highly flammable. The factory made plastic dolls and soft toys such as stuffed rabbits, elephants and pigs for an international market, mainly the United States. The toys were produced for Disney, Mattel, Tyco, Kenner, Toys-R-Us and other leading companies. Among the items manufactured there were Cabbage Patch and Bart Simpson dolls, both very popular at the time. Because of all the combustible materials, security guards were unable to extinguish the flames and the fire quickly spread to all four stories of Building One. About 20 minutes after the fire started guards called the fire department. The first firefighters arrived after about 20 more minutes to find Building One perilously close to collapse. Less than an hour after the Nakhon Pathom fire brigade was called the building came down, trapping many workers inside. By then the fire had spread to Buildings Two and Three. Overwhelmed by the scale of the disaster, the Nakhon Pathom crew chief called for additional units from Bangkok, about 30 kilometres away. But because of the usual evening traffic congestion in the capital and around the factory, it was some time before fresh firefighting crews arrived. Before it was over about some 300 firemen with 50 fire engines were battling the fire, along with a large number of volunteers. It wasn’t enough to prevent the collapse of Buildings Two and Three; Building Two came down at around 5.30pm and Building Three about 30 minutes later. |

| Fortunately almost all of the workers in these two buildings were able to escape unharmed. Building Four and other buildings in the factory compound were unaffected by the fire. Fleets of ambulances and other vehicles ferried injured workers to more than 20 hospitals in Nakhon Pathom, Nonthaburi and Bangkok provinces. According to medical sources, about half of the injured were treated for smoke inhalation and most of the rest for multiple fractures, including skull fractures. Many workers were treated for burns as well. A large number of life-saving surgeries were performed. It is very difficult to find follow-up medical records on the injured. For example, it is believed that a significant number of victims suffered permanent paralysis, but the exact numbers are not known. Finding fault For two weeks after the tragedy relatives streamed to a makeshift mortuary near the factory to identify their loved ones. The bodies of many of the victims in Building One were burned beyond recognition. Around 200 soldiers from the First Development Regiment were deployed to help search through the debris and remove bodies from the rubble. It took over two weeks to recover the bodies of all victims. Meanwhile, survivors’ reports emerged claiming that no fire alarm had sounded in Building One. Fire alarms did go off in Buildings Two and Three, and only a few minor injuries were reported in these buildings. It’s unclear whether fire alarms in Building One were out of order or even installed. Many workers said they had no clue there was a fire until they could smell smoke. There were reports that fire safety drills had been nonexistent. Sprinkler systems were not installed in any of the buildings. There was a public clamour to determine who was at fault. The first culprit produced was a factory worker, Viroj Yusak. He was accused of starting the fire by carelessly discarding a cigarette. Despite conflicting reports and theories on how the fire started, Viroj was convicted in a Nakhon Pathom court and sentenced to 10 years in jail. |

It should be noted that investigators were unable to make a positive determination of what started the fire because the section of Building One where it started was totally destroyed. Moreover, stories from survivors didn’t match up. The investigators put these theories forward: (1) As the fire started near a large electrical control panel, problems with the electrical system might have been the cause; (2) Arson; (3) A carelessly discarded cigarette may have been the source of ignition; (4) The fire may have started when sparks from a shorted circuit ignited synthetic materials used to stuff toys.

It will probably never be known which if any of these theories is correct. What does seem clear is that disregard for proper fire safety practices was a major factor in the high casualty toll. Yet no one besides Viroj was ever held legally accountable in any way for the tragedy. A Nakhon Pathom court allegedly cleared 14 Kader executives, including the factory’s managing director, an engineer and a shareholder, of all charges. The only legal recognition of Kader Industrial’s culpability was a fine of 520,000 baht.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the ICFTU published a report titled, “From the Ashes – A Toy Factory in Thailand”. The report gave some background on the corporate structure of the toy company. Here are some excerpts: “Kader Industrial (Thailand) Co., Ltd. began manufacturing in 1988 and set up the Thai Chui-fu Holding as a publicly listed company in 1990, with 20 percent shares traded in Thailand’s stock market.

“In Thailand, Kader was set up as a foreign joint venture with the CP (Charoen Pokphand) Group. The Thailand-based CP Group, in turn, created a company in Hong Kong known as Honbo Investment. Honbo Investment and Kader Industrial then formed another company, KCP Toys, also listed in Hong Kong.”

Legacy of negligence

In February 2011, the ILO Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety website presented its own report on the Kader fire: “Case Study: The Kader Toy Factory Fire” also saying: “Kader Industrial (Thailand) Co., Ltd. was first registered on January 27, 1989, but the company’s licence was suspended on November 21, 1989, after a fire on August 16, 1989, that destroyed the new plant. After the plant was rebuilt, the Ministry of Industry allowed the factory to reopen on July 4, 1990.

“Between the time the factory re-opened and the May 1993 fire, the facility experienced several other, smaller fires. One of them, which occurred in February 1993, did considerable damage to Building Three, which was still being repaired at the time of the fire on May 10, 1993.

“Several days after the [February] blaze a labour inspector visited the site and issued a warning that pointed out the plant’s need for safety officers, safety equipment and an emergency plan.”

Other reports on the May 1993 fire point out that the factory was poorly designed and constructed; fire exits drawn in the building plans were not actually constructed; external doors that did exist were locked; the building was reinforced with steel girders that quickly lost integrity and collapsed because of the high heat.

It will probably never be known which if any of these theories is correct. What does seem clear is that disregard for proper fire safety practices was a major factor in the high casualty toll. Yet no one besides Viroj was ever held legally accountable in any way for the tragedy. A Nakhon Pathom court allegedly cleared 14 Kader executives, including the factory’s managing director, an engineer and a shareholder, of all charges. The only legal recognition of Kader Industrial’s culpability was a fine of 520,000 baht.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the ICFTU published a report titled, “From the Ashes – A Toy Factory in Thailand”. The report gave some background on the corporate structure of the toy company. Here are some excerpts: “Kader Industrial (Thailand) Co., Ltd. began manufacturing in 1988 and set up the Thai Chui-fu Holding as a publicly listed company in 1990, with 20 percent shares traded in Thailand’s stock market.

“In Thailand, Kader was set up as a foreign joint venture with the CP (Charoen Pokphand) Group. The Thailand-based CP Group, in turn, created a company in Hong Kong known as Honbo Investment. Honbo Investment and Kader Industrial then formed another company, KCP Toys, also listed in Hong Kong.”

Legacy of negligence

In February 2011, the ILO Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety website presented its own report on the Kader fire: “Case Study: The Kader Toy Factory Fire” also saying: “Kader Industrial (Thailand) Co., Ltd. was first registered on January 27, 1989, but the company’s licence was suspended on November 21, 1989, after a fire on August 16, 1989, that destroyed the new plant. After the plant was rebuilt, the Ministry of Industry allowed the factory to reopen on July 4, 1990.

“Between the time the factory re-opened and the May 1993 fire, the facility experienced several other, smaller fires. One of them, which occurred in February 1993, did considerable damage to Building Three, which was still being repaired at the time of the fire on May 10, 1993.

“Several days after the [February] blaze a labour inspector visited the site and issued a warning that pointed out the plant’s need for safety officers, safety equipment and an emergency plan.”

Other reports on the May 1993 fire point out that the factory was poorly designed and constructed; fire exits drawn in the building plans were not actually constructed; external doors that did exist were locked; the building was reinforced with steel girders that quickly lost integrity and collapsed because of the high heat.

| Compensation fight Academics, trade unions and nongovernmental organisations joined victims, their families and supporters in efforts to receive proper compensation. The coalition resulted in the ‘Working Group for the Support of Kader Workers’. Under pressure from the Working Group, CP eventually acknowledged its connection to the factory. The Working Group threatened to organise an international boycott of Kader products and attracted media attention sufficient to bring Kader representatives to negotiations for increased compensation. According to the ICFTU report: “A memorandum of agreement was signed on July 13, 1993, and resulted in a several fold increase of compensation coverage by Kader. Up to US$12,000 was added to the total compensation package per individual by Kader instead of the original US$4,000 that was offered. This was subject to the victims and families agreeing not to later pursue legal action for compensation.” | |

From the ICFTU report: “Kader agreed to pay additional medical costs not covered by government compensation. Monthly education payments for the children of deceased parents and minimum payments to short-term workers would not have been included as compensation either.

“Kader agreed to pay for additional medical costs not covered by government compensation. Monthly education payments for the children of deceased parents and minimum payments to short-term workers would not have been included as compensation either.

“Kader also agreed, eventually, to offer suitable jobs (in an eventual new operation) to injured workers, to the relatives of the victims and to the workers previously employed there for three or more years. Finally, Kader agreed to pay all outstanding salaries, overtime payments, annual holiday payments and all amounts for compensation to the government for disbursement.”

“Kader agreed to pay for additional medical costs not covered by government compensation. Monthly education payments for the children of deceased parents and minimum payments to short-term workers would not have been included as compensation either.

“Kader also agreed, eventually, to offer suitable jobs (in an eventual new operation) to injured workers, to the relatives of the victims and to the workers previously employed there for three or more years. Finally, Kader agreed to pay all outstanding salaries, overtime payments, annual holiday payments and all amounts for compensation to the government for disbursement.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed