Heavily armed and threatening to execute hostages, a group of Burmese dissidents who took over the embassy eventually negotiated their way out of Thailand in a Thai police helicopter

By Maxmilian Wechsler

ON October 1, 1999, a group of gunmen stormed the Embassy of Myanmar (then commonly called Burma) in Bangkok and held scores of hostages for about 26 hours. The bold operation was the work of a band of young political dissidents calling themselves the Vigorous Burmese Student Warriors (VBSW). Formed in opposition to Myanmar’s then-ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), the group was allegedly orchestrated and supervised by Western intelligence agency operatives.

The tense standoff at the embassy compound was totally out of character for Myanmar opposition groups operating in Thailand and soured the image of the large exile population in the country. Fortunately the bizarre incident ended peacefully when all hostages were released unharmed.

This was actually the second seizure of a foreign embassy on Thai soil. The first took place on December 29, 1972, when the Palestinian terrorist Black September Organization took over the Israeli embassy. This incident also ended bloodlessly with the release of all hostages.

The tense standoff at the embassy compound was totally out of character for Myanmar opposition groups operating in Thailand and soured the image of the large exile population in the country. Fortunately the bizarre incident ended peacefully when all hostages were released unharmed.

This was actually the second seizure of a foreign embassy on Thai soil. The first took place on December 29, 1972, when the Palestinian terrorist Black September Organization took over the Israeli embassy. This incident also ended bloodlessly with the release of all hostages.

Embassy under siege

Five armed members of VBSW, regarded by some as a terrorist organisation, invaded the embassy compound on North Sathorn Road around 11am on Friday, October 1, 1999. The assailants entered through the main gate unchallenged, carrying four AK-47 assault rifles hidden inside two guitar cases and several egg-shaped hand grenades. They allegedly obtained the war weapons from the group known as God’s Army, which had a base on the Thai-Myanmar border.

Embassy security guard Thamonsak Amorndet, a private in the Royal Thai Police force attached to the Special Branch, was in the sentry box when the invaders entered. One of them pulled a rifle from the guitar case and hit him on the head with it. The guard’s black CZ Czech-made semi-automatic pistol was taken from him.

It was reported that prior to the armed assault several hard-line members of another opposition group were spotted on Pan Road, where a side entrance to the embassy’s visa section was located. Some of them apparently carried first-aid kits, presumably to provide medical assistance to VBSW members if needed. A local intelligence source claimed that several agents from a Western intelligence agency were seen in the vicinity of the embassy as well, as reported in a local English language newspaper.

Five armed members of VBSW, regarded by some as a terrorist organisation, invaded the embassy compound on North Sathorn Road around 11am on Friday, October 1, 1999. The assailants entered through the main gate unchallenged, carrying four AK-47 assault rifles hidden inside two guitar cases and several egg-shaped hand grenades. They allegedly obtained the war weapons from the group known as God’s Army, which had a base on the Thai-Myanmar border.

Embassy security guard Thamonsak Amorndet, a private in the Royal Thai Police force attached to the Special Branch, was in the sentry box when the invaders entered. One of them pulled a rifle from the guitar case and hit him on the head with it. The guard’s black CZ Czech-made semi-automatic pistol was taken from him.

It was reported that prior to the armed assault several hard-line members of another opposition group were spotted on Pan Road, where a side entrance to the embassy’s visa section was located. Some of them apparently carried first-aid kits, presumably to provide medical assistance to VBSW members if needed. A local intelligence source claimed that several agents from a Western intelligence agency were seen in the vicinity of the embassy as well, as reported in a local English language newspaper.

The five invaders were led by Kyaw Ni, aka “Big Johnny”, who was easily identified as he was a well-known figure in the Myanmar exile community and didn’t cover his face. He was described by other exiles as impulsive, erratic and hard to control. One exile leader called him a “crazy man.”

Once inside the VBSW quickly took control of close to 90 hostages, mostly Thai nationals and foreigners from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and the US who were apparently there for visas. Thirteen embassy staff and diplomats, including the first and second secretary were also taken hostage.

Myanmar’s ambassador to Thailand at the time, U Hla Maung, left the embassy about 15 minutes before the attack. One source speculated that someone inside the embassy had colluded with the hostage-takers and that this person gave the signal for them to enter only after the ambassador had left.

After an alarm was raised, police vehicles, ambulances and fire engines raced to the scene from all directions. The police closed North Sathorn Road and cordoned off nearby streets. Anti-terrorist squads wearing flak jackets and armed with assault rifles and shotguns surrounded the embassy, assisted by police canine units.

Sharpshooters with M-16 rifles, some with sniper scopes, positioned themselves on a high-rise building close to the embassy. They were under orders not to fire to give negotiators a chance to secure freedom for the hostages.

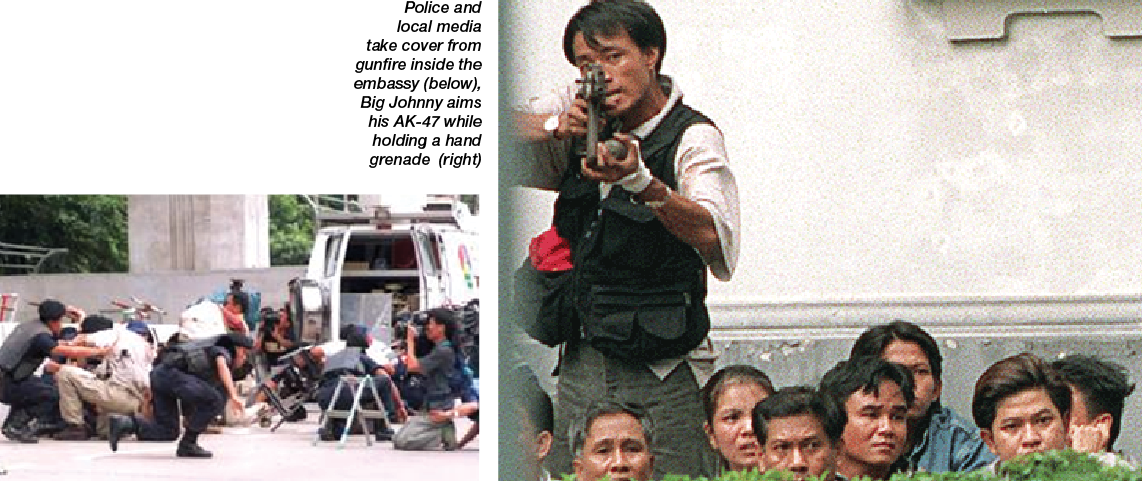

Within minutes several TV satellite trucks arrived to broadcast live coverage from outside the embassy to viewers in Thailand and around the world. Thai and foreign journalists converged on the scene, with some getting dangerously close to the gate guarded by Big Johnny, who was holding an AK-47 and a hand grenade and looking very much in charge.

The VBSW sent a fax from inside the embassy to local media detailing a list of demands for the SPDC. These included freeing political prisoners, starting a dialogue with the opposition, convening the Parliament elected in 1990, and a helicopter to take the hostage-takers to the Thai-Myanmar border. It’s certain that the VBSW had no hopes that any of these demands would be met, except the last one.

The true aims of the bold embassy seizure were more complex. Despite a statement from the newly formed VBSW saying “this action is [initiated by] our own movement and our own ideas”, there is good reason to believe the group was following the agenda of some longtime actors in the Myanmar power struggle.

Standoff ends in negotiation

Faced with a potentially lethal situation, Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai instructed the relevant authorities to negotiate with the hostage-takers until the siege was resolved. In the evening he visited the negotiations command centre set up in the nearby Bayer building for a briefing. Thai officials including Interior Minister Sanan Kachornprasart and General Pornsak Durongkavibul, deputy head of the national police, led the negotiations and coordinated with various agencies. Interior Minister Sanan told the media that force would not be used to resolve the situation.

Back at the embassy, Big Johnny threatened to execute one hostage every 30 minutes until an escape helicopter arrived, but no hostage was harmed after the deadline passed. Thai negotiators and the terrorists yelled out to each other over the embassy wall and one brave official standing close to the gate was using a handheld megaphone.

At one point the gunmen lowered the flag of Myanmar inside the compound and replaced it with a banner showing a yellow bird on a red background, the symbol of the anti-junta movement. When several pistol shots were fired in succession to salute the flag, policemen, journalists and onlookers ran for cover.

The pistol that fired the shots was probably the one taken from the security guard. By the next morning, five hostages had escaped or were released, among them Pte Thamonsak. He appeared disoriented when led by fellow policemen to a waiting ambulance. A scar on his face from a rifle blow was clearly visible. He was taken to hospital and later released.

A police helicopter was seen circling over the embassy, but it was unable to land in the small compound as demanded by the VBSW. Therefore, it was agreed to use an empty field near the Armed Forces Academy Preparatory School next to Lumpini Park.

White vans with tinted windows were on hand for foreign hostages, VBSW members and Thai officials to board. It took the vans only a few minutes to reach the field where the police helicopter was waiting after midday. Some of the hostages were wearing pro-democracy headbands, waving the opposition flag and shouting slogans calling for freedom in Myanmar. Their overenthusiastic display led some to believe they were with the VBSW all along.

After the hostages were released the terrorists boarded the helicopter, joined by Deputy Foreign Minister Sukhumbhand Paribatra and Chaiyapruik Sawaengcharoen, an official in charge of refugees in Thailand. Both offered themselves as surrogate hostages.

A short time later the helicopter landed safely at the God’s Army base, about 90-kilometres west of Bangkok and just across the Thai-Myanmar border. It was reported that the VBSW were welcomed by a jubilant group of God’s Army soldiers led by Shwe Bya. The VBSW were equipped with expensive satellite phones given to them by a supporter. Mobile phones are useless in the mountains along the Thai-Myanmar border. After delivering the VBSW to the remote base, the police helicopter returned to Bangkok with Mr Sukhumband and Mr Chaiyapruik.

There’s no information on whether the students loitering in the vicinity actually entered the compound after the assault, and if so, how they left.

Aftermath

International condemnation of the embassy seizure came from all sides, including the US State Department spokesman James Rubin said the US considered it a “terrorist attack, regardless of the motives and demands of the gunmen.”

The response from Thai officials was more muted. In explaining the decision to provide safe passage for the gunmen, Interior Minister Sanan described the hostage-takers as “students fighting for democracy in their own country.” He said they were not terrorists, as the SPDC called them. After returning from the helicopter trip, Mr Sukhumbhand echoed these sentiments: “They are just students fighting in favour of democracy.”

Such comments from Thai officials, along with the failure to protect the Myanmar Embassy and the decision to allow the gunmen to depart instead of arresting them and putting them on trial, greatly upset the SPDC. They retaliated quickly by closing border crossings with Thailand and effectively halting all trade. They also closed Myanmar waters to Thai fishing boats, resulting in huge losses for Thai fishermen.

Suchart Brirattana, head of the Mae Sai Chamber of Commerce, said that the border closure was costing Thai businesses 25 million baht a day in lost trade. Sutha Theareepat, the head of provincial Fisheries Department in Ranong, said fishing and related businesses lost some 43 million baht a day. Following negotiations between the Thai and Myanmar governments the border was reopened, on November 24, 1999.

The leader of the opposition National League for Democracy, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (DASSK), issued a statement deploring the attack. So did the majority of dissident leaders based in Thailand. They agreed that the incident was a big setback for the opposition movement, as the Thai government and people had turned against them. They feared that the Thai government would take steps to retaliate against them and make it hard for them to operate inside Thailand even though they had nothing to do with the siege, and they were right. The Thai government banned demonstrations outside the Myanmar embassy, closed offices of pro-democracy and human rights groups in Thailand, and rounded up many Myanmar workers and deported them.

About a week after the siege the Thai government issued warrants for the arrest of five people believed to have taken part in it. They were each charged with nine separate offenses, including illegal detention and possession of firearms, robbery, and hijacking.

Once inside the VBSW quickly took control of close to 90 hostages, mostly Thai nationals and foreigners from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and the US who were apparently there for visas. Thirteen embassy staff and diplomats, including the first and second secretary were also taken hostage.

Myanmar’s ambassador to Thailand at the time, U Hla Maung, left the embassy about 15 minutes before the attack. One source speculated that someone inside the embassy had colluded with the hostage-takers and that this person gave the signal for them to enter only after the ambassador had left.

After an alarm was raised, police vehicles, ambulances and fire engines raced to the scene from all directions. The police closed North Sathorn Road and cordoned off nearby streets. Anti-terrorist squads wearing flak jackets and armed with assault rifles and shotguns surrounded the embassy, assisted by police canine units.

Sharpshooters with M-16 rifles, some with sniper scopes, positioned themselves on a high-rise building close to the embassy. They were under orders not to fire to give negotiators a chance to secure freedom for the hostages.

Within minutes several TV satellite trucks arrived to broadcast live coverage from outside the embassy to viewers in Thailand and around the world. Thai and foreign journalists converged on the scene, with some getting dangerously close to the gate guarded by Big Johnny, who was holding an AK-47 and a hand grenade and looking very much in charge.

The VBSW sent a fax from inside the embassy to local media detailing a list of demands for the SPDC. These included freeing political prisoners, starting a dialogue with the opposition, convening the Parliament elected in 1990, and a helicopter to take the hostage-takers to the Thai-Myanmar border. It’s certain that the VBSW had no hopes that any of these demands would be met, except the last one.

The true aims of the bold embassy seizure were more complex. Despite a statement from the newly formed VBSW saying “this action is [initiated by] our own movement and our own ideas”, there is good reason to believe the group was following the agenda of some longtime actors in the Myanmar power struggle.

Standoff ends in negotiation

Faced with a potentially lethal situation, Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai instructed the relevant authorities to negotiate with the hostage-takers until the siege was resolved. In the evening he visited the negotiations command centre set up in the nearby Bayer building for a briefing. Thai officials including Interior Minister Sanan Kachornprasart and General Pornsak Durongkavibul, deputy head of the national police, led the negotiations and coordinated with various agencies. Interior Minister Sanan told the media that force would not be used to resolve the situation.

Back at the embassy, Big Johnny threatened to execute one hostage every 30 minutes until an escape helicopter arrived, but no hostage was harmed after the deadline passed. Thai negotiators and the terrorists yelled out to each other over the embassy wall and one brave official standing close to the gate was using a handheld megaphone.

At one point the gunmen lowered the flag of Myanmar inside the compound and replaced it with a banner showing a yellow bird on a red background, the symbol of the anti-junta movement. When several pistol shots were fired in succession to salute the flag, policemen, journalists and onlookers ran for cover.

The pistol that fired the shots was probably the one taken from the security guard. By the next morning, five hostages had escaped or were released, among them Pte Thamonsak. He appeared disoriented when led by fellow policemen to a waiting ambulance. A scar on his face from a rifle blow was clearly visible. He was taken to hospital and later released.

A police helicopter was seen circling over the embassy, but it was unable to land in the small compound as demanded by the VBSW. Therefore, it was agreed to use an empty field near the Armed Forces Academy Preparatory School next to Lumpini Park.

White vans with tinted windows were on hand for foreign hostages, VBSW members and Thai officials to board. It took the vans only a few minutes to reach the field where the police helicopter was waiting after midday. Some of the hostages were wearing pro-democracy headbands, waving the opposition flag and shouting slogans calling for freedom in Myanmar. Their overenthusiastic display led some to believe they were with the VBSW all along.

After the hostages were released the terrorists boarded the helicopter, joined by Deputy Foreign Minister Sukhumbhand Paribatra and Chaiyapruik Sawaengcharoen, an official in charge of refugees in Thailand. Both offered themselves as surrogate hostages.

A short time later the helicopter landed safely at the God’s Army base, about 90-kilometres west of Bangkok and just across the Thai-Myanmar border. It was reported that the VBSW were welcomed by a jubilant group of God’s Army soldiers led by Shwe Bya. The VBSW were equipped with expensive satellite phones given to them by a supporter. Mobile phones are useless in the mountains along the Thai-Myanmar border. After delivering the VBSW to the remote base, the police helicopter returned to Bangkok with Mr Sukhumband and Mr Chaiyapruik.

There’s no information on whether the students loitering in the vicinity actually entered the compound after the assault, and if so, how they left.

Aftermath

International condemnation of the embassy seizure came from all sides, including the US State Department spokesman James Rubin said the US considered it a “terrorist attack, regardless of the motives and demands of the gunmen.”

The response from Thai officials was more muted. In explaining the decision to provide safe passage for the gunmen, Interior Minister Sanan described the hostage-takers as “students fighting for democracy in their own country.” He said they were not terrorists, as the SPDC called them. After returning from the helicopter trip, Mr Sukhumbhand echoed these sentiments: “They are just students fighting in favour of democracy.”

Such comments from Thai officials, along with the failure to protect the Myanmar Embassy and the decision to allow the gunmen to depart instead of arresting them and putting them on trial, greatly upset the SPDC. They retaliated quickly by closing border crossings with Thailand and effectively halting all trade. They also closed Myanmar waters to Thai fishing boats, resulting in huge losses for Thai fishermen.

Suchart Brirattana, head of the Mae Sai Chamber of Commerce, said that the border closure was costing Thai businesses 25 million baht a day in lost trade. Sutha Theareepat, the head of provincial Fisheries Department in Ranong, said fishing and related businesses lost some 43 million baht a day. Following negotiations between the Thai and Myanmar governments the border was reopened, on November 24, 1999.

The leader of the opposition National League for Democracy, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (DASSK), issued a statement deploring the attack. So did the majority of dissident leaders based in Thailand. They agreed that the incident was a big setback for the opposition movement, as the Thai government and people had turned against them. They feared that the Thai government would take steps to retaliate against them and make it hard for them to operate inside Thailand even though they had nothing to do with the siege, and they were right. The Thai government banned demonstrations outside the Myanmar embassy, closed offices of pro-democracy and human rights groups in Thailand, and rounded up many Myanmar workers and deported them.

About a week after the siege the Thai government issued warrants for the arrest of five people believed to have taken part in it. They were each charged with nine separate offenses, including illegal detention and possession of firearms, robbery, and hijacking.

|

Shwe Bya hands over the stolen pistol

Road to the meeting point

|

THE STORY BEHIND THE SIEGE

AT the time of the Myanmar embassy seizure I was a regular contributor to the New Era Journal (NEJ), a monthly opposition anti-SPDC newspaper published in Thailand by a senior leader of the opposition named U Tin Maung Win. I was a close friend of his and also got to know many opposition leaders and members of political and armed groups, including God’s Army and the Karen National Union (KNU). I learned through a source that the VBSW leader, Ye Thi Ha, alias San Naing, participated in the siege. Despite a past criminal record that included two airplane hijackings, the source said he was working for and protected by one Western intelligence agency. A Thai official told me that before the embassy siege began, God’s Army soldiers under the command of Shwe Bya - a former soldier in the KNU’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army - were preparing a landing spot for a helicopter inside Myanmar, just opposite Ratchaburi province. This was confirmed by Padu Kwe Htoo Win, leading KNU member and Chairman of Mergui-Tavoy district where God’s Army was operating. “God’s Army had cleared the forest to make a helicopter landing pad about 300-400 metres from the Thai border inside Myanmar, long before the embassy siege began,” Kwe Htoo said. He admitted he wasn’t “happy” when in June 1999 a leader of the Karen Solidarity Organisation (KSO) brought 12 VBSW members to God’s Army headquarters in the Thai village of Takolan adjacent to Karen state. It was widely known that the KSO leader had connections to a Western intelligence agency. The VBSW members were introduced to Saw Toe Toe, secretary-general of God’s Army, who took them to a camp inside Myanmar in September. |

|

According to security sources, one country benefited considerably from the embassy siege. These sources said the last of the three vans that left the embassy didn’t carry hostages but a large quantity of documents the VBSW had extracted from the embassy during the siege, packed in black rubbish bags. The van continued down Witthayu Road and entered an embassy there, say the sources.

One of the sources claimed that during the siege the VBSW gunmen possibly Big Johnny opened a vault inside the ambassador’s office. Many documents were removed, some top secret, relating to narcotics and identifying informers working for foreign countries and SPDC spies operating in Thailand. Whoever opened the vault knew the combination of the safe, said the source. No one was killed or seriously injured during the siege, but one life was arguably lost as a result of it – that of U Tin Maung Win, who had a long association with certain Western intelligence agencies. Mr Win received a phone call in October and was asked to proceed to an embassy on Witthayu Road, and to keep it secret. Once there, he was told to sort out documents taken from the Myanmar embassy and separate them into stacks according to importance and classification. Mr Win was prevented from leaving the embassy. His family was greatly concerned when he didn’t return home that night and called his friends, including myself, to ask if they had any information. It was a big relief when he finally returned home after few days. Mr Win died on December 1, 1999, allegedly from heart failure. I last saw him in late November after he’d met with some foreign intelligence officers, just three days before his sudden death. At the hotel coffee shop where we met he was very nervous and made emphatic gestures with his hands, causing him to overturn a glass of water on the table. I had never seen him in such distress. |

U Tin Maung Win

Padu Kwe Htoo Win

|

“They wanted me to do something, but I told them that I am not going to do that,” Maung Win said during our conversation. When I asked him what they wanted – I had some idea who ‘they’ were – he said nothing.

Three days later he said he was “ordered” to move the NEJ office to a “more secure” location. He didn’t have to spell out who gave the order. He absolutely didn’t want to make the move, nor did his family. During the move he collapsed and died while carrying a desktop computer. His daughter called me to tell me the news, and in follow-up calls she described details of what happened immediately after his death which are not possible to reveal even after 17 years.

Regrettably, no autopsy was performed. There were rumours within the exile community that he was poisoned a few days before his death, causing heart failure.

Among the many wreaths at his funeral at a Bangkok temple was one delivered by a man on a motorcycle who quickly disappeared. The acronym VBSW on the wreath was clearly visible. The funeral was attended by hundreds of people, including intelligence agents. Some of them appeared to be studying the crowd and some were inside a white van parked outside, taking photos of the mourners.

VBSW hand over pistol

No policeman likes to lose his weapon. Due to my connections within the Myanmar’s dissident community, I was asked by a special Thai Army unit in charge of Myanmar border affairs to retrieve the pistol taken from Pol Pte Thamonsak in the embassy siege. I asked a long-time friend, Saw Thaw Thi, to help negotiate the return of the weapon. The KNU member was based on the border and knew God’s Army leaders who had influence with the VBSW.

Under pressure from several sides, the VBSW agreed to return the pistol. Saw Thaw Thi worked out the arrangements with Shwe Bya, the God’s Army military commander, for the return of the weapon and guarantees of my safety.

The Army unit agreed with the deal, and I was given the serial number of the gun and dropped off on the outskirts of Takolan on October 24, 1999. After a short walk along a designated road, I was met by Saw Thaw Thi, who took me to a shack where Shwe Bya was waiting with several unarmed God’s Army soldiers.

Shwe Bya handed me the gun on behalf of the VBSW. Saw Thaw Thi and I checked the serial number, which was a match. God’s Army videotaped the transaction. Shwe Bya then gave me a sealed letter from the VBSW addressed to Prime Minister Chuan. I then carried the gun and the letter to a spot where a Thai Army unit was waiting with vehicles and we sped away.

In the letter dated October 12, the VBSW apologised for their actions and offered an explanation of the motives behind the embassy takeover. They requested a meeting with PM Chuan, which was rejected. Nevertheless, the gesture from the VBSW encouraged the Thai government.

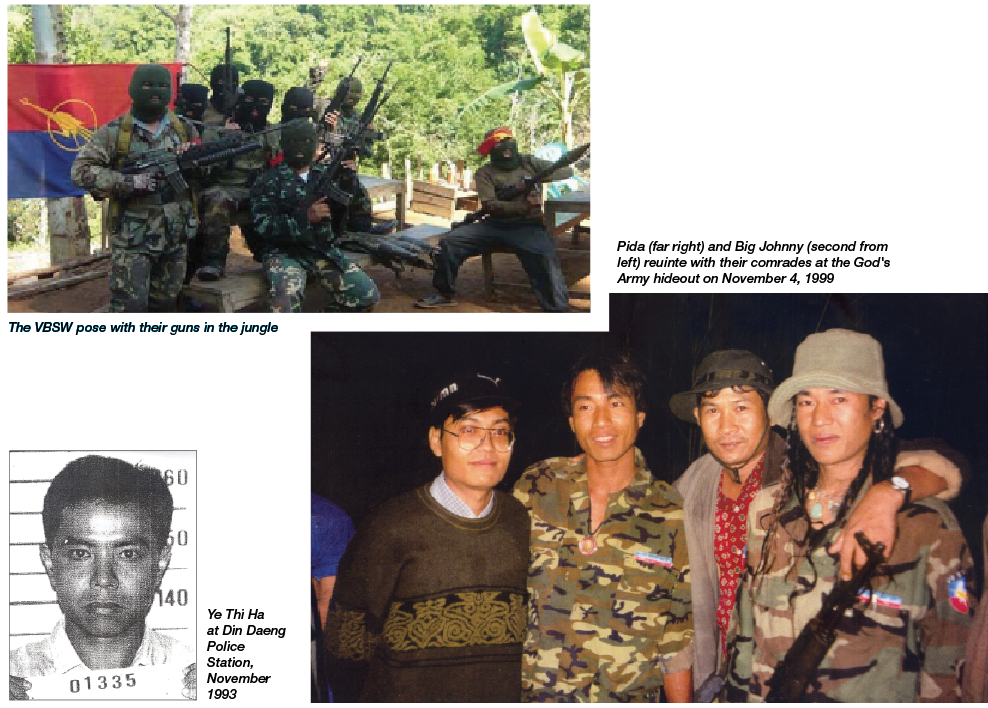

Under pressure from the government, two VBSW members who were staying at the Maneeloy holding camp for refugees promised to try to convince Kyaw Ni and a mysterious and obviously influential figure known as Pida, both staying with God’s army, to surrender. They went to the God’s Army base with their appeal and it was tentatively accepted.

I agreed to meet with Kyaw Ni and Pida in a jungle area on the border to discuss terms of surrender on November 4, accompanied by a team from the same Thai Army unit. We were supported by a large contingent of Thai soldiers and Border Patrol Police (BPP). It was a rainy night. We finally reached the Army base a few kilometres from the actual meeting point. I then left the base and went with several plain-clothed Thai Army men, two BPP men and the two VBSW negotiators to the designated spot in the middle of nowhere.

Suddenly, from out of nowhere, around 30 youthful and fully armed God’s Army soldiers – among them the twins, Johnny and Luther Htoo – appeared and encircled our group. With them were Kyaw Ni and Pida, both brandishing AK-47s. The situation was clearly humiliating for the Thai military and police, especially since we were on Thai soil. I relayed the terms of surrender promised by PM Chuan. For what they had done against Thailand it was good deal. Pida was quiet and reasonable, but Kyaw Ni was combative and seemed very agitated. He refused the conditions.

I told him: “You can trust the PM. He is waiting for you personally right now. Please come with us.” He suddenly pointed his AK-47 directly at me at close range and had to be restrained by the two VBSW members. “I don’t believe these promises,” he said. “If I surrender then I will be arrested and jailed for a long time, and I don’t want to go to jail.”

Several VBSW members who arrived from Maneeloy camp also pleaded with Kyaw Ni and Pida to give up. Finally, Kyaw Ni said he would let the twins decide his and Pida’s fate. A Karen interpreter asked the twins: “Do you want Big Johnny and Pida to leave us [God’s Army] and go with the Thai officers?’’ Both said: “Yes, we want them to go.”

But the interpreter, acting on orders from Shwe Bya, said the exact opposite. This came out during a recent email interview I did with Luther, who along with his brother is now living in America. The deliberate mistranslation was confirmed by another person who was there as well. Had the interpreter not twisted the twins’ words, the Ratchaburi Hospital tragedy would probably never have occurred.

Kyaw Ni and Pida vanished into the darkness. Thai officers talked to the twins and other God’s Army members at the dark, remote site for about an hour and were convinced they didn’t want the two older men to stay with them, but couldn’t evict them.

We returned safely to the base camp, where the commander requested permission from his superior to fire 120mm mortars at the rebels. The large calibre mortars were buried in bunkers and ready for action. The superior decided to let the rebels walk the several kilometres back to their camp inside Myanmar.

When we arrived at the Army base in Suan Phung, a large group of reporters was waiting at the main gate. They had heard something big was going on and raced there from Bangkok.

Later on, a VBSW member disclosed to me that Kyaw Ni and Pida had originally intended to surrender that night. He claimed that a certain third party (believed to be with a Western intelligence agency) had learned of their intentions and warned them that if they surrendered they would be jailed for many years in Thailand or transferred to Myanmar to face execution by the SPDC. “Obviously, someone was afraid that they might reveal secrets to Thai investigators or the media that could incriminate certain people,” said the VBSW source.

I recalled that just before the meeting in the jungle two colonels from the special unit had expressed worries that intelligence operatives might find out about the meeting and warn Kyaw Ni and Pida by satellite phone that they must not surrender.

Some years later Kyaw Ni was killed under mysterious circumstances following a meeting arranged by a Karen man with two exile leaders on the Thai-Myanmar border. They told him to give up, but he again refused. After the exiles left someone who knew about the meeting killed Big Johnny. The exiles insisted that they had nothing to do with the killing and only later realised the meeting was a setup.

Pida was killed by the Thai commandos who stormed Ratchaburi Hospital on January 24, 2000 after it was taken over by God’s Army.

An article on the seizure of the hospital will be published in the March issue of The BigChilli.

Three days later he said he was “ordered” to move the NEJ office to a “more secure” location. He didn’t have to spell out who gave the order. He absolutely didn’t want to make the move, nor did his family. During the move he collapsed and died while carrying a desktop computer. His daughter called me to tell me the news, and in follow-up calls she described details of what happened immediately after his death which are not possible to reveal even after 17 years.

Regrettably, no autopsy was performed. There were rumours within the exile community that he was poisoned a few days before his death, causing heart failure.

Among the many wreaths at his funeral at a Bangkok temple was one delivered by a man on a motorcycle who quickly disappeared. The acronym VBSW on the wreath was clearly visible. The funeral was attended by hundreds of people, including intelligence agents. Some of them appeared to be studying the crowd and some were inside a white van parked outside, taking photos of the mourners.

VBSW hand over pistol

No policeman likes to lose his weapon. Due to my connections within the Myanmar’s dissident community, I was asked by a special Thai Army unit in charge of Myanmar border affairs to retrieve the pistol taken from Pol Pte Thamonsak in the embassy siege. I asked a long-time friend, Saw Thaw Thi, to help negotiate the return of the weapon. The KNU member was based on the border and knew God’s Army leaders who had influence with the VBSW.

Under pressure from several sides, the VBSW agreed to return the pistol. Saw Thaw Thi worked out the arrangements with Shwe Bya, the God’s Army military commander, for the return of the weapon and guarantees of my safety.

The Army unit agreed with the deal, and I was given the serial number of the gun and dropped off on the outskirts of Takolan on October 24, 1999. After a short walk along a designated road, I was met by Saw Thaw Thi, who took me to a shack where Shwe Bya was waiting with several unarmed God’s Army soldiers.

Shwe Bya handed me the gun on behalf of the VBSW. Saw Thaw Thi and I checked the serial number, which was a match. God’s Army videotaped the transaction. Shwe Bya then gave me a sealed letter from the VBSW addressed to Prime Minister Chuan. I then carried the gun and the letter to a spot where a Thai Army unit was waiting with vehicles and we sped away.

In the letter dated October 12, the VBSW apologised for their actions and offered an explanation of the motives behind the embassy takeover. They requested a meeting with PM Chuan, which was rejected. Nevertheless, the gesture from the VBSW encouraged the Thai government.

Under pressure from the government, two VBSW members who were staying at the Maneeloy holding camp for refugees promised to try to convince Kyaw Ni and a mysterious and obviously influential figure known as Pida, both staying with God’s army, to surrender. They went to the God’s Army base with their appeal and it was tentatively accepted.

I agreed to meet with Kyaw Ni and Pida in a jungle area on the border to discuss terms of surrender on November 4, accompanied by a team from the same Thai Army unit. We were supported by a large contingent of Thai soldiers and Border Patrol Police (BPP). It was a rainy night. We finally reached the Army base a few kilometres from the actual meeting point. I then left the base and went with several plain-clothed Thai Army men, two BPP men and the two VBSW negotiators to the designated spot in the middle of nowhere.

Suddenly, from out of nowhere, around 30 youthful and fully armed God’s Army soldiers – among them the twins, Johnny and Luther Htoo – appeared and encircled our group. With them were Kyaw Ni and Pida, both brandishing AK-47s. The situation was clearly humiliating for the Thai military and police, especially since we were on Thai soil. I relayed the terms of surrender promised by PM Chuan. For what they had done against Thailand it was good deal. Pida was quiet and reasonable, but Kyaw Ni was combative and seemed very agitated. He refused the conditions.

I told him: “You can trust the PM. He is waiting for you personally right now. Please come with us.” He suddenly pointed his AK-47 directly at me at close range and had to be restrained by the two VBSW members. “I don’t believe these promises,” he said. “If I surrender then I will be arrested and jailed for a long time, and I don’t want to go to jail.”

Several VBSW members who arrived from Maneeloy camp also pleaded with Kyaw Ni and Pida to give up. Finally, Kyaw Ni said he would let the twins decide his and Pida’s fate. A Karen interpreter asked the twins: “Do you want Big Johnny and Pida to leave us [God’s Army] and go with the Thai officers?’’ Both said: “Yes, we want them to go.”

But the interpreter, acting on orders from Shwe Bya, said the exact opposite. This came out during a recent email interview I did with Luther, who along with his brother is now living in America. The deliberate mistranslation was confirmed by another person who was there as well. Had the interpreter not twisted the twins’ words, the Ratchaburi Hospital tragedy would probably never have occurred.

Kyaw Ni and Pida vanished into the darkness. Thai officers talked to the twins and other God’s Army members at the dark, remote site for about an hour and were convinced they didn’t want the two older men to stay with them, but couldn’t evict them.

We returned safely to the base camp, where the commander requested permission from his superior to fire 120mm mortars at the rebels. The large calibre mortars were buried in bunkers and ready for action. The superior decided to let the rebels walk the several kilometres back to their camp inside Myanmar.

When we arrived at the Army base in Suan Phung, a large group of reporters was waiting at the main gate. They had heard something big was going on and raced there from Bangkok.

Later on, a VBSW member disclosed to me that Kyaw Ni and Pida had originally intended to surrender that night. He claimed that a certain third party (believed to be with a Western intelligence agency) had learned of their intentions and warned them that if they surrendered they would be jailed for many years in Thailand or transferred to Myanmar to face execution by the SPDC. “Obviously, someone was afraid that they might reveal secrets to Thai investigators or the media that could incriminate certain people,” said the VBSW source.

I recalled that just before the meeting in the jungle two colonels from the special unit had expressed worries that intelligence operatives might find out about the meeting and warn Kyaw Ni and Pida by satellite phone that they must not surrender.

Some years later Kyaw Ni was killed under mysterious circumstances following a meeting arranged by a Karen man with two exile leaders on the Thai-Myanmar border. They told him to give up, but he again refused. After the exiles left someone who knew about the meeting killed Big Johnny. The exiles insisted that they had nothing to do with the killing and only later realised the meeting was a setup.

Pida was killed by the Thai commandos who stormed Ratchaburi Hospital on January 24, 2000 after it was taken over by God’s Army.

An article on the seizure of the hospital will be published in the March issue of The BigChilli.

VIGOROUS BURMESE STUDENT WARRIORS

THE Vigorous Burmese Student Warriors group was born at Maneeloy Holding Centre 120 kilometres southwest of Bangkok on August 29, 1999, just two days before they stormed the Myanmar Embassy. The group listed 18 founding members; first on the list was Ye Thi Ha, alias Sai Naing, followed by Min Lwin and Kyaw Ni, better known as “Big Johnny.”

Ye Thi Ha began his “fight fordemocracy” by hijacking a Burmese domestic flight from Mergui to Rangoon on October 6, 1989, along with an accomplice by the name of Ye Yint. The men forced the pilot of the Fokker F-28 to land at U-Tapao Thai Naval Air Base. After 11 hours of negotiations, they released all 82 passengers and four crew members unharmed. They were arrested and sentenced to six years in jail, but were released for good behaviour after serving three years each.

Ye Thi Ha didn’t enjoy his freedom for long. In November 1993, Din Daeng district police in Bangkok arrested him and three Burmese friends for possession of weapons and explosives. The group allegedly planned to enter Myanmar and assassinate government leaders during the National Day celebrations of January 1994. They each received sentences of five years and four months, but were released in February 1997. Ye Thi Ha was deported to Myanmar on October 5 that year.

He and the VBSW conducted terrorists operations in Myanmar and in Thailand, including the 1999 embassy siege in Bangkok and the takeover of the Ratchaburi hospital. The group was relatively quiet for a while before grabbing headlines again on December 23, 2004, when they distributed a media release to news organisations claiming responsibility for the bombing of Zawgi Restaurant in Rangoon two days earlier. According to Reuters, the blast killed one employee of the restaurant which was popular among foreign tourists, but other media reported only an injury.

The VBSW warned that more bombings would follow unless the military regime agreed to immediately release all political prisoners, including DASSK, and hand over the state power to the National League for Democracy (NLD), which won a landslide victory in the 1990 general election. DASSK and her NLD swiftly condemned the bombing.

After the Ratchaburi Hospital siege, thanks to good police work Ye Thi Ha was finally located in the Saphan Kwai area of Bangkok. But according to one policeman, while a police unit waited outside his apartment ready to arrest him, a phone call came with an order to abort the operation, lending credence to the suggestion that Ye Thi Ha worked for a Western intelligence agency.

The VBSW reportedly halted operations or were disbanded after 2013 as reforms took place in Myanmar.

THE Vigorous Burmese Student Warriors group was born at Maneeloy Holding Centre 120 kilometres southwest of Bangkok on August 29, 1999, just two days before they stormed the Myanmar Embassy. The group listed 18 founding members; first on the list was Ye Thi Ha, alias Sai Naing, followed by Min Lwin and Kyaw Ni, better known as “Big Johnny.”

Ye Thi Ha began his “fight fordemocracy” by hijacking a Burmese domestic flight from Mergui to Rangoon on October 6, 1989, along with an accomplice by the name of Ye Yint. The men forced the pilot of the Fokker F-28 to land at U-Tapao Thai Naval Air Base. After 11 hours of negotiations, they released all 82 passengers and four crew members unharmed. They were arrested and sentenced to six years in jail, but were released for good behaviour after serving three years each.

Ye Thi Ha didn’t enjoy his freedom for long. In November 1993, Din Daeng district police in Bangkok arrested him and three Burmese friends for possession of weapons and explosives. The group allegedly planned to enter Myanmar and assassinate government leaders during the National Day celebrations of January 1994. They each received sentences of five years and four months, but were released in February 1997. Ye Thi Ha was deported to Myanmar on October 5 that year.

He and the VBSW conducted terrorists operations in Myanmar and in Thailand, including the 1999 embassy siege in Bangkok and the takeover of the Ratchaburi hospital. The group was relatively quiet for a while before grabbing headlines again on December 23, 2004, when they distributed a media release to news organisations claiming responsibility for the bombing of Zawgi Restaurant in Rangoon two days earlier. According to Reuters, the blast killed one employee of the restaurant which was popular among foreign tourists, but other media reported only an injury.

The VBSW warned that more bombings would follow unless the military regime agreed to immediately release all political prisoners, including DASSK, and hand over the state power to the National League for Democracy (NLD), which won a landslide victory in the 1990 general election. DASSK and her NLD swiftly condemned the bombing.

After the Ratchaburi Hospital siege, thanks to good police work Ye Thi Ha was finally located in the Saphan Kwai area of Bangkok. But according to one policeman, while a police unit waited outside his apartment ready to arrest him, a phone call came with an order to abort the operation, lending credence to the suggestion that Ye Thi Ha worked for a Western intelligence agency.

The VBSW reportedly halted operations or were disbanded after 2013 as reforms took place in Myanmar.

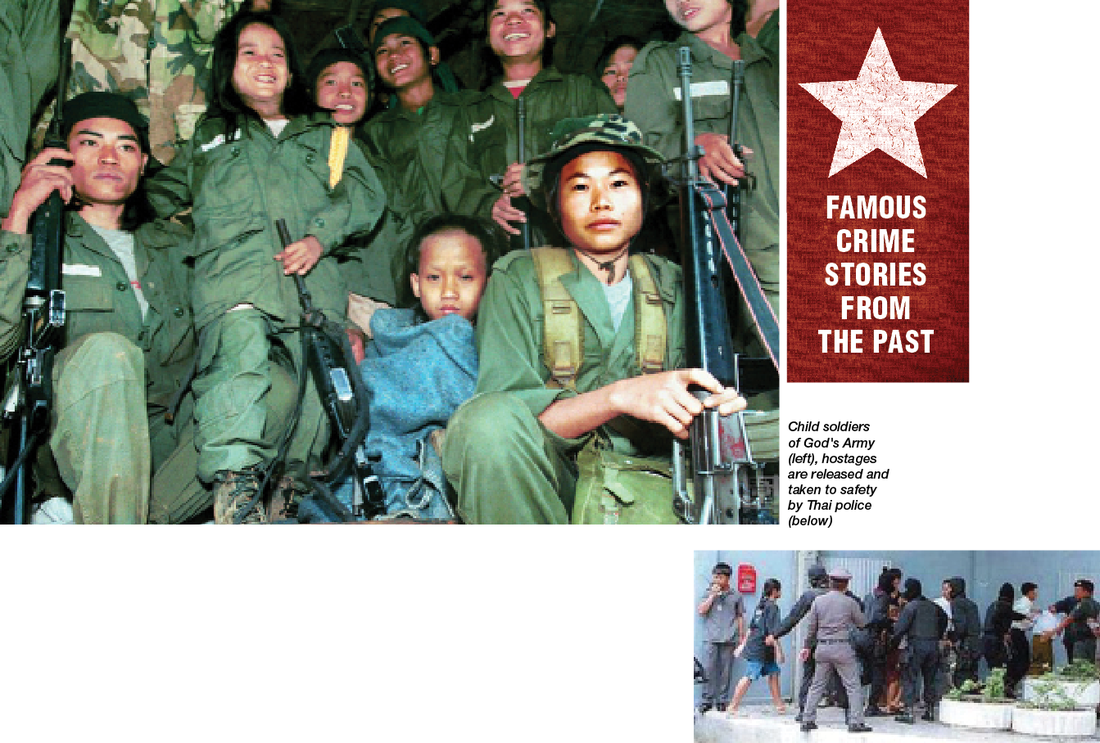

GOD’S ARMY

GOD’S Army was formed by a Karen pastor named Thape on March 7, 1997, after a decision in February by about 200 deeply religious and superstitious Karen Christian families to abandon the villages they had lived in for centuries in the Tavoy area of Myanmar and flee to Thailand to escape ongoing persecution by the ruling military junta. During the journey to the Thai border, eight-year-old twins Johnny and Luther Htoo claimed to have had a vision of God commanding them to lead their young compatriots to fight against the SPDC.

Most of the God’s Army child soldiers and their families, including the family of Johnny and Luther, lived in Takolan in Ratchaburi province, on the Thai side of the border a few kilometres from Suan Phung town. God’s Army members frequently crossed the border to their headquarters in Myanmar. Johnny and Luther were merely the spiritual leaders and had little say in the group’s planning and operations. These were under Shwe Bya, the God’s Army military commander who manipulated the twins.

Between 1997 and 2000, God’s Army had about 200 young soldiers. They proved to be a formidable force from the start and their remarkable battlefield victories against the SPDC made them famous and feared. Some of the victories were attributed to the twins’ alleged powers. God’s Army soon caught the attention of various foreign groups which donated money and materials to them. Among the biggest donors was a South Korean religious group that financed the construction of a church at Takolan.

Several young South Koreans who said they were missionaries frequently visited Suan Phung. Some told me they used to work for Korean security agencies, while others said they were formerly members of a security detail guarding the South Korean president. A Thai officer said this group was actually a proxy for one Western intelligence service.

In June 1999 God’s Army was introduced to the VBSW, which took advantage of their innocence. They convinced God’s Army they would be better off joining in future VBSW military operations. The VBSW gave the young soldiers uniforms, food, medicine, weapons, and ammunition in return for their support. God’s Army soldiers swallowed the bait because some greedy people among them controlled the twins.

Instead of focusing their military efforts against the SPDC, the VBSW attacked two targets inside Thailand: The Burmese Embassy in Bangkok and the Ratchaburi hospital. God’s Army soldiers blindly participated in these events, which had catastrophic consequences for both groups because they made enemies of the Thai government

and people.

On January 16 and 17, 2001, a group of 17 exhausted remnants of God’s Army that included Johnny and Luther surrendered to Thai authorities. PM Chuan met the twins at Suan Phung BPP headquarters on January 17 and spoke to them briefly through an interpreter. General Surayud Chulanont, then Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Thai Army, was present during the surrender as well.

GOD’S Army was formed by a Karen pastor named Thape on March 7, 1997, after a decision in February by about 200 deeply religious and superstitious Karen Christian families to abandon the villages they had lived in for centuries in the Tavoy area of Myanmar and flee to Thailand to escape ongoing persecution by the ruling military junta. During the journey to the Thai border, eight-year-old twins Johnny and Luther Htoo claimed to have had a vision of God commanding them to lead their young compatriots to fight against the SPDC.

Most of the God’s Army child soldiers and their families, including the family of Johnny and Luther, lived in Takolan in Ratchaburi province, on the Thai side of the border a few kilometres from Suan Phung town. God’s Army members frequently crossed the border to their headquarters in Myanmar. Johnny and Luther were merely the spiritual leaders and had little say in the group’s planning and operations. These were under Shwe Bya, the God’s Army military commander who manipulated the twins.

Between 1997 and 2000, God’s Army had about 200 young soldiers. They proved to be a formidable force from the start and their remarkable battlefield victories against the SPDC made them famous and feared. Some of the victories were attributed to the twins’ alleged powers. God’s Army soon caught the attention of various foreign groups which donated money and materials to them. Among the biggest donors was a South Korean religious group that financed the construction of a church at Takolan.

Several young South Koreans who said they were missionaries frequently visited Suan Phung. Some told me they used to work for Korean security agencies, while others said they were formerly members of a security detail guarding the South Korean president. A Thai officer said this group was actually a proxy for one Western intelligence service.

In June 1999 God’s Army was introduced to the VBSW, which took advantage of their innocence. They convinced God’s Army they would be better off joining in future VBSW military operations. The VBSW gave the young soldiers uniforms, food, medicine, weapons, and ammunition in return for their support. God’s Army soldiers swallowed the bait because some greedy people among them controlled the twins.

Instead of focusing their military efforts against the SPDC, the VBSW attacked two targets inside Thailand: The Burmese Embassy in Bangkok and the Ratchaburi hospital. God’s Army soldiers blindly participated in these events, which had catastrophic consequences for both groups because they made enemies of the Thai government

and people.

On January 16 and 17, 2001, a group of 17 exhausted remnants of God’s Army that included Johnny and Luther surrendered to Thai authorities. PM Chuan met the twins at Suan Phung BPP headquarters on January 17 and spoke to them briefly through an interpreter. General Surayud Chulanont, then Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Thai Army, was present during the surrender as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed