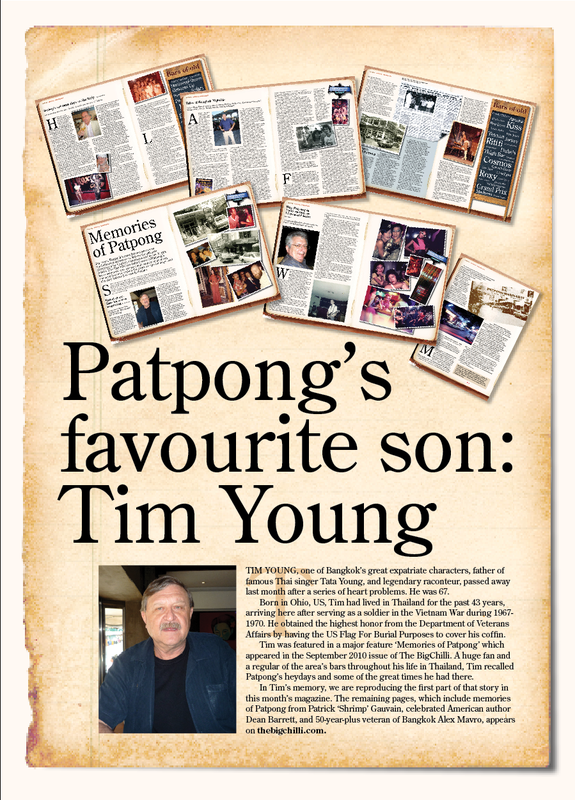

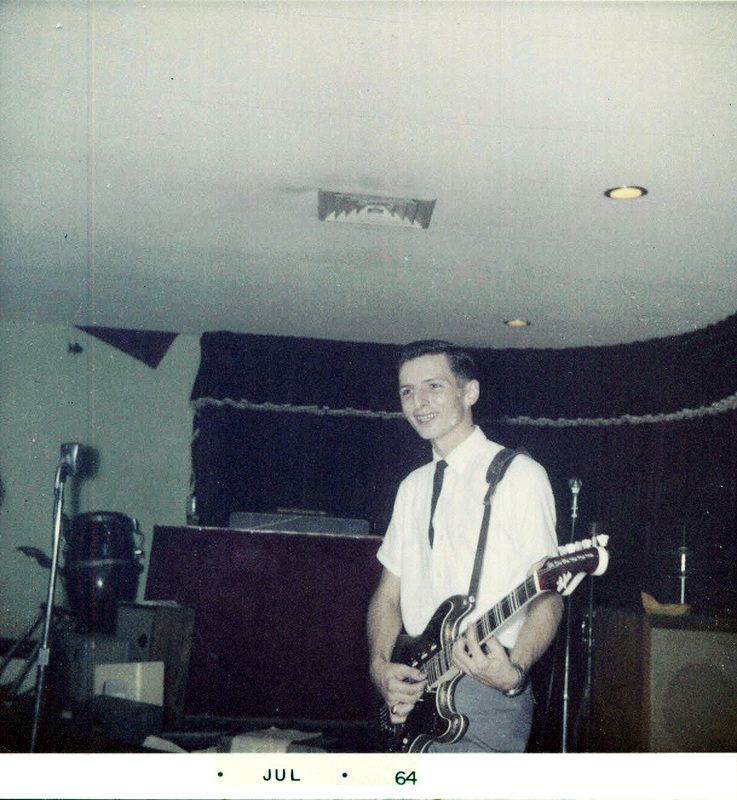

| TIM YOUNG, one of Bangkok’s great expatriate characters, father of famous Thai singer Tata Young, and legendary raconteur, passed away last month after a series of heart problems. He was 67. Born in Ohio, US, Tim had lived in Thailand for the past 43 years, arriving here after serving as a soldier in the Vietnam War during 1967-1970. He obtained the highest honor from the Department of Veterans Affairs by having the US Flag For Burial Purposes to cover his coffin. Tim was featured in a major feature ‘Memories of Patpong’ which appeared in the September 2010 issue of The BigChilli. A huge fan and a regular of the area’s bars throughout his life in Thailand, Tim recalled Patpong’s heydays and some of the great times he had there. The article also featured memories of Patpong from Patrick ‘Shrimp’ Gauvain, celebrated American author Dean Barrett, and 50-year-plus veteran of Bangkok Alex Mavro. In Tim’s memory, we have reproduced the story here in its entirety. |

Memories of Patpong

For years, Bangkok’s most famous street was unchallenged anywhere in Asia as the ultimate playground for tourists, expatriates and locals. In this report, The BigChilli has invited some of Patpong’s best customers over the past half century to go down memory lane and explain the district’s special magic and why they believe it is now in decline

STREET of Dreams or Bangkok’s Road of Shame? Either way, this small thoroughfare has been a magnet over the years for countless people who might not otherwise have come to Thailand. With its glory days well behind it, and the number of visitor falling steadily, speculation about Patpong’s future is inevitable. Some say the market which is often blamed for the area’s decline will be moved to nearby premises while others reckon that a new style of entertainment is needed to replace the go-go bars that once enthralled audiences. Fewer visitors to Patpong has also affected dozens of other nearby businesses that relied on the street’s popularity for their survival. Change is in the air, and for many it can’t come quickly enough.

For years, Bangkok’s most famous street was unchallenged anywhere in Asia as the ultimate playground for tourists, expatriates and locals. In this report, The BigChilli has invited some of Patpong’s best customers over the past half century to go down memory lane and explain the district’s special magic and why they believe it is now in decline

STREET of Dreams or Bangkok’s Road of Shame? Either way, this small thoroughfare has been a magnet over the years for countless people who might not otherwise have come to Thailand. With its glory days well behind it, and the number of visitor falling steadily, speculation about Patpong’s future is inevitable. Some say the market which is often blamed for the area’s decline will be moved to nearby premises while others reckon that a new style of entertainment is needed to replace the go-go bars that once enthralled audiences. Fewer visitors to Patpong has also affected dozens of other nearby businesses that relied on the street’s popularity for their survival. Change is in the air, and for many it can’t come quickly enough.

Faded glory - time for a new beginning By Colin Hastings

Long time resident Tim Young recalls the rise and fall of Patpong

FOR old Patpong hands, the Strip has simply lost it. The glitz, the excitement and all those wonderful possibilities that mesmerized and massaged so many male egos have all disappeared, along with the tourists and the fabulous amounts of money that once poured into the area.

Business is down, badly. So what’s the long-term prognosis for this infamous and probably most expensive piece of Bangkok real estate?

“Dismal,” reckons one long-term go-go bar owner who’s seen his takings tumble to 80% of what they were in the street’s glory days in the late 80s.

It’s now just a matter of survival for this old hand. “I’ll continue here only for as long as I can still make a living, of sorts,” he says.

He’s not alone. Many other Patpong businesses are also clearly struggling – and that’s not likely to change until the street’s owners decide on a new future for the area, which is actually rumored to be on the cards.

Ask regulars what caused the street’s decline, and they’ll blame the market, which first appeared tentatively in the late 80s before morphing into a major shopping mall in 1991.

But that’s only half the story, according to Tim Young, a larger-than-life American who probably knows Patpong’s past, present and even its future better than any other foreigner.

“You also have to look at the high rents now being charged,” says Tim, who first came to Thailand with the US military in the late 60s and went on to open one of the street’s first bars, the Bad Apple, in 1971. “It’s so expensive to run a bar there today.”

Tim’s assertion is backed by present-day tenants, who reckon that rent on even a small unit on the Strip is now in excess of 200,000 baht “plus four months’ advance.”

At the same time, the whole of Patpong has undergone something of a ‘morality check’ in recent years, with the authorities cracking down on the raunchier aspects of its character. “This hasn’t happened in Soi Cowboy or Nana,” growls Tim.

“Over there, almost anything still goes.”

Oddly enough, the crackdown hasn’t extended to touts, who continue to plague Patpong and yet barely exist in Bangkok’s other red light districts.

Often mentioned as another reason for the area’s decline is the dominance of two business groups who operate the majority of Patpong’s bars. “Basically, with their buying power they are able to control the price of almost everything, from beer and hostess drinks to even the exit fee for a girl,” says one independent bar owner.

When it comes to remembering the area’s glory days, no one does it better than Tim. His memory is phenomenal. In a moment, he can recall names and faces of the many characters, good and bad, who once frequented the area, including the rich and famous as well as gangsters, drug runners, foreigners who made and lost fortunes, mamasans and “all of their husbands” and, of course, the countless girls who passed through Patpong over the years.

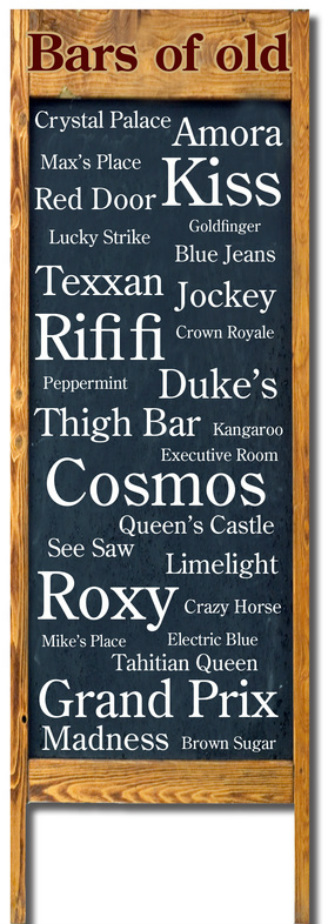

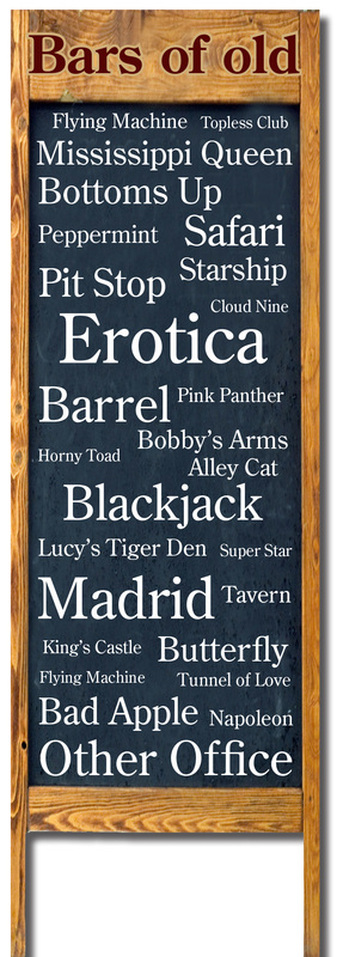

He can also list the bars that came and went and even stayed over the years, including his all-time favorite, Super Star, which he took over for a night in 1986 to celebrate his 50th birthday. “What a night that was,” grins Tim, father and manager of Thailand’s top international singer Tata Young.

As an aside, he reels off the price of drinks charged in Patpong’s early days. “Beer 10 baht at happy hour and 15 baht thereafter, Coke eight baht and 10 baht, and mixed drinks 10 and 15 baht. Buying out a girl was 50 baht. And gasoline was one baht a litre.”

Tim naturally laments the passing of the old Patpong but is nonetheless cheered by a rumour now doing the rounds that its owners are currently renovating the large building

at the Suriwongse end of the Strip and turning the first three or four floors into a MBK-style shopping mall. Vendors now occupying the main street will be offered preferential rates, thus freeing the area for visitors and tourists to walk unheeded.

Times and tastes have changed since the 1970s and Patpong will never reprise its former role. But there is hope that it can once again become a major attraction and help to revive a part of Bangkok badly in need of revival.

Long time resident Tim Young recalls the rise and fall of Patpong

FOR old Patpong hands, the Strip has simply lost it. The glitz, the excitement and all those wonderful possibilities that mesmerized and massaged so many male egos have all disappeared, along with the tourists and the fabulous amounts of money that once poured into the area.

Business is down, badly. So what’s the long-term prognosis for this infamous and probably most expensive piece of Bangkok real estate?

“Dismal,” reckons one long-term go-go bar owner who’s seen his takings tumble to 80% of what they were in the street’s glory days in the late 80s.

It’s now just a matter of survival for this old hand. “I’ll continue here only for as long as I can still make a living, of sorts,” he says.

He’s not alone. Many other Patpong businesses are also clearly struggling – and that’s not likely to change until the street’s owners decide on a new future for the area, which is actually rumored to be on the cards.

Ask regulars what caused the street’s decline, and they’ll blame the market, which first appeared tentatively in the late 80s before morphing into a major shopping mall in 1991.

But that’s only half the story, according to Tim Young, a larger-than-life American who probably knows Patpong’s past, present and even its future better than any other foreigner.

“You also have to look at the high rents now being charged,” says Tim, who first came to Thailand with the US military in the late 60s and went on to open one of the street’s first bars, the Bad Apple, in 1971. “It’s so expensive to run a bar there today.”

Tim’s assertion is backed by present-day tenants, who reckon that rent on even a small unit on the Strip is now in excess of 200,000 baht “plus four months’ advance.”

At the same time, the whole of Patpong has undergone something of a ‘morality check’ in recent years, with the authorities cracking down on the raunchier aspects of its character. “This hasn’t happened in Soi Cowboy or Nana,” growls Tim.

“Over there, almost anything still goes.”

Oddly enough, the crackdown hasn’t extended to touts, who continue to plague Patpong and yet barely exist in Bangkok’s other red light districts.

Often mentioned as another reason for the area’s decline is the dominance of two business groups who operate the majority of Patpong’s bars. “Basically, with their buying power they are able to control the price of almost everything, from beer and hostess drinks to even the exit fee for a girl,” says one independent bar owner.

When it comes to remembering the area’s glory days, no one does it better than Tim. His memory is phenomenal. In a moment, he can recall names and faces of the many characters, good and bad, who once frequented the area, including the rich and famous as well as gangsters, drug runners, foreigners who made and lost fortunes, mamasans and “all of their husbands” and, of course, the countless girls who passed through Patpong over the years.

He can also list the bars that came and went and even stayed over the years, including his all-time favorite, Super Star, which he took over for a night in 1986 to celebrate his 50th birthday. “What a night that was,” grins Tim, father and manager of Thailand’s top international singer Tata Young.

As an aside, he reels off the price of drinks charged in Patpong’s early days. “Beer 10 baht at happy hour and 15 baht thereafter, Coke eight baht and 10 baht, and mixed drinks 10 and 15 baht. Buying out a girl was 50 baht. And gasoline was one baht a litre.”

Tim naturally laments the passing of the old Patpong but is nonetheless cheered by a rumour now doing the rounds that its owners are currently renovating the large building

at the Suriwongse end of the Strip and turning the first three or four floors into a MBK-style shopping mall. Vendors now occupying the main street will be offered preferential rates, thus freeing the area for visitors and tourists to walk unheeded.

Times and tastes have changed since the 1970s and Patpong will never reprise its former role. But there is hope that it can once again become a major attraction and help to revive a part of Bangkok badly in need of revival.

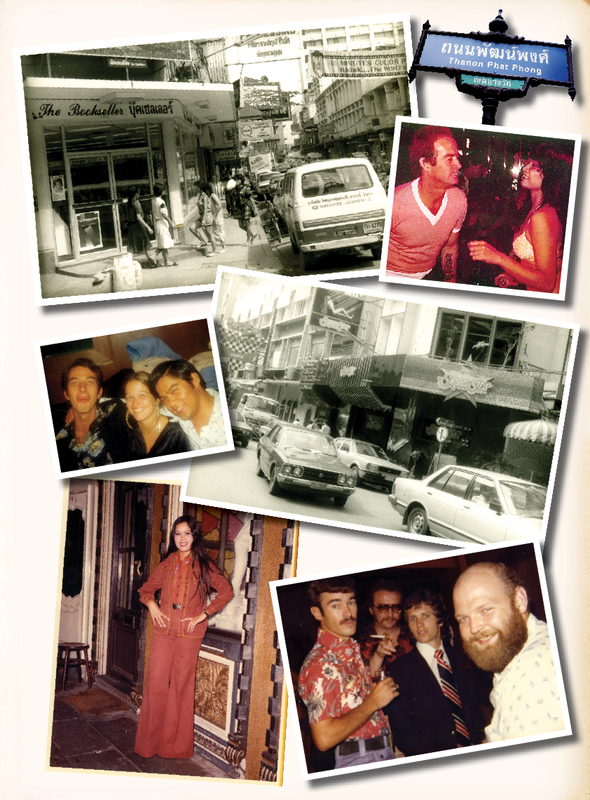

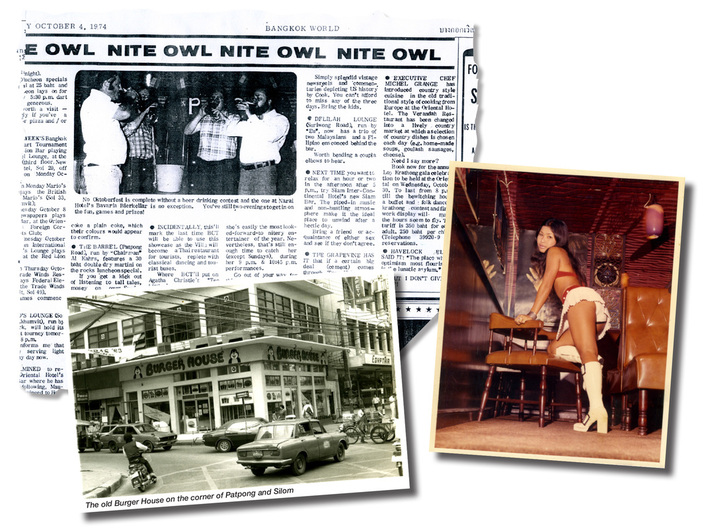

| When taxis cruised Patpong UNTIL its recent decline in popularity, Patpong would attract thousands of visitors. More often than not, it would turn into a horrible scrum of people competing for space with the area’s workers, vendors, pimps and ubiquitous touts. This hasn’t always been the case. Back in the 1970s Patpong was still a relatively quiet backwater, drawing a few hundred punters nightly, despite the fact that it was already beginning to punch well above its weight in the way it had spiked the world’s curiosity. Closing time for the dozen or so bars was midnight from Sunday to Thursday, and 1am at weekends. Right on cue, bright lights were switched on to signal the end of business. Customers would drift onto the pavement outside, though often delaying their departure from the Strip in order to see who had got lucky that night. For dancers tired and hungry after the evening shift, the pavement served another purpose - as a makeshift restaurant. Vendors with baskets of food across their shoulders would simply stop wherever they were hailed and then served the girls who squatted nimbly on the sidewalk in groups of two or three. In a scene unimaginable today, many of these ‘instant’ sidewalk diners were a regular feature of Patpong back then. Meanwhile, customers would be heading off home. And getting there couldn’t have been easier – you just hailed one of the many taxis that cruised the street at closing time. So light was the traffic that they had free access to Patpong even at its busiest moment. From today’s perspective of massive congestion, this is another hard-to-imagine scene. |

Even more improbable, however, were the antics of a group of foreigners who frequented one of the smaller bars in the early 70s. Extended lunches fuelled by copious alcohol would culminate in a game, a sort of Russian roulette Bangkok-style, in which the unlucky fellow who’d drawn the short straw was required to rush out of the bar at full speed and, with eyes closed, run to the other side of Patpong without stopping.

They did this, of course, in the fairly secure knowledge that Patpong mid-afternoon was a decidedly sleepy place with little or no chance of a passing car or truck. At least that was the theory and since no fatalities were ever reported, we have to assume that the mad runners made it to the other side.

Such pranks don’t happen these days. That’s not because of a shortage of takers. But because a street market would get in the way.

They did this, of course, in the fairly secure knowledge that Patpong mid-afternoon was a decidedly sleepy place with little or no chance of a passing car or truck. At least that was the theory and since no fatalities were ever reported, we have to assume that the mad runners made it to the other side.

Such pranks don’t happen these days. That’s not because of a shortage of takers. But because a street market would get in the way.

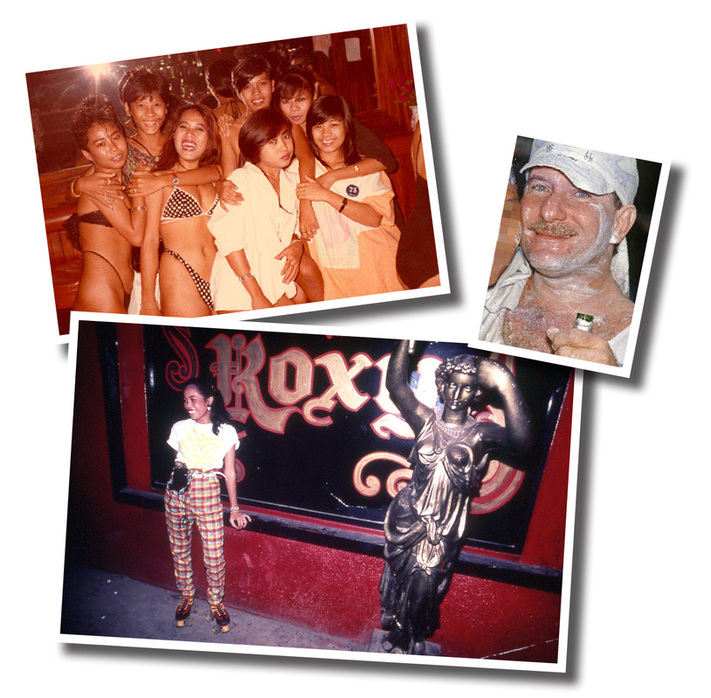

Shrimp now and having fun, below, back in the 80s

Shrimp now and having fun, below, back in the 80s Shrimp’s celebrity days on the Strip By Colin Hastings

For more than two decades, Patrick Gauvain was the toast of Patpong

HE reckons it took “about 15 minutes” to discover Patpong on his first visit to Bangkok back in September 1968, and for the next two decades there was hardly a night of the week when Patrick ‘Shrimp’ Gauvain wasn’t cruising the street and indulging in its nocturnal pleasures.

Few knew Patpong in its heyday better than Shrimp, a photographer-turned-advertising guru, now in his sixties, with business interests in Thailand, China, the Philippines and Dubai.

With his command of the Thai language, cheeky grin and penchant for the outrageous, he was for years one of the Strip’s best known celebrities, surrounded by friends who could trade off his many liaisons, and instantly recognized by the bikini-clad demimondes who found his brand of charm utterly irresistible.

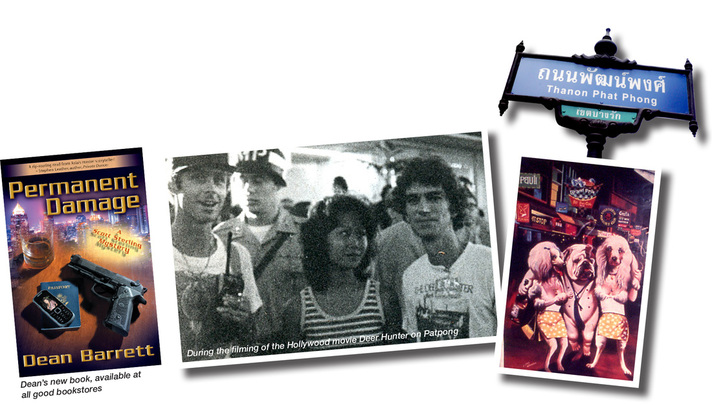

So when international movie stars and the like came to town and inquired discreetly, as they would, after Bangkok’s naughtiest street, Shrimp was the obvious choice to show them around. Among those with whom he shared his inside track were the actor Robert de Niro and controversial movie producer Roman Polanski.

In 1974, during the filming in southern Thailand of the James Bond movie ‘Man with the Golden Gun’ he was asked to introduce Patpong’s garish lights to two cast members, the Swedish beauty Ekland and midget actor Herve Villechaize. Rumor has it that the pint-sized Frenchman was immediately captivated by what he saw and for a while became one of the street’s busiest players, wooing the girls with his generosity and promises. There’s no record, however, of Ekland ever returning.

Today, Shrimp recalls those early days in Patpong as an era of relative innocence. “It’s very different now compared to back then,” he says. “The real action in the late 60s was happening over at New Petchburi Road, where US soldiers on R&R from Vietnam would congregate in places like Jack’s All American Star Bar and Thai Heaven. They would rarely venture beyond that area, and certainly not to the other side of town.

“Patong was tame by comparison, with places like Mizu’s, a restaurant that offered massage by Japanese girls to Japanese soldiers during the Second World War, but that was long ago. Then there was Patpong Café, plus a few tailor shops, airline offices, Ted Bates advertising agency and not much else.”

That all changed in late 1968, says Shrimp, when an American by the name of Rick Meynard opened a flashy bar on Patpong called Grand Prix and introduced a feature that would become the unofficial symbol of the street – the go-go dancer. In Rick’s original format, a go-go was nothing more than a girl dancing on an upturned box. Nonetheless, Patpong suddenly had something new and exciting to pull in the customers. And Petchburi’s days as the city’s top entertainment area for foreigners were over.

Grand Prix eventually spawned dozens of other bars offering go-go, including Safari whose dancers shared the stage with snakes and wild cats, and the legendary Mississippi Queen, or MQ, which specialized in soul music to appeal to Black American soldiers on rest and recreation.

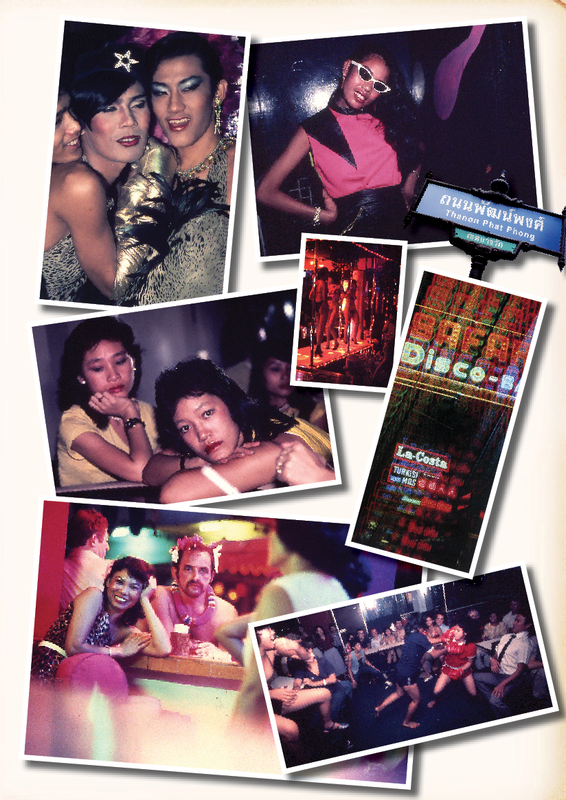

“By this time Patpong had evolved, albeit slowly, from a quiet road into an extremely raunchy street of dreams,” remembers Shrimp, who was born in Malaysia to British parents.

In the early 1970s, his favourite hang-out was MQ, partly due to the music but also to the beauty and energy of its dancers. “So much more inventive than today’s girls,” he smiles, clearly relishing the memory.

The street’s edgy nature attracted all sorts of foreigners, mostly fun-loving characters but also the odd charlatan, wise guys and one visitor in particular who was imbued with unspeakable evil. There was, for example, the owner-manager of MQ who was caught trying to ship soft drugs to Australia, imprisoned and then released, only to reoffend far more seriously and sentenced to virtual life behind bars. Others tried to recruit new arrivals to carry packets of T-shirts with concealed bundles of ganja to Australia, while itinerant salesmen were always trying to palm off highly questionable life insurance policies.

The worst by far, however, was the notorious Indian-Vietnamese mass murderer Charles Sobhraj, who would befriend young foreign backpackers in Bangkok, drug and then kill them in a reign of evil that extended across Asia. “MQ was Sobhraj’s favourite haunt. I saw him there many times,” recalls Shrimp, who like many others was taken in by the easy-going Vietnamese-Indian, completely unaware that his victims were meeting their end in a nearby apartment house.

Following the closure of MQ in the mid-80s, Shrimp switched his attention to bars like Safari, Limelight and Peppermint.

“If I wanted to meet up with my mates, these are the places I’d go on a Friday or Saturday at about 9pm, because I just knew without checking beforehand that they’d be there.”

With closing time extended to 2am and beyond, Patpong was Bangkok’s leading late-night party venue. Alcohol-fuelled nights sometimes ended in disaster, however, such as the time Shrimp broke his leg while playfully chasing a dancer around the stage. It wasn’t long before the street’s most ardent womanizer returned, leg in plaster and hobbling on crutches, but with the same old enthusiasm.

| Looking at Patpong today, with its congested street market and impersonality, it’s hard to imagine the friendliness of the street a couple of decades ago. It was without doubt Bangkok’s hottest area, a melting pot of tourists, expatriates and curious locals, all on the town for the same reason. But honestly, were the go-go girls better looking back then? “Hard to say because we are all older and more selective nowadays, so whatever we chased back then, we probably wouldn’t chase now,” says the man whose famous calendars of nude Patpong dancers scandalized both him and the street, but which also probably did more than any single promotion to attract tourists to this part of Bangkok. Because of his long association with the street, it’s perhaps not surprising that Shrimp is generous and forgiving whenever the subject of Patpong’s ladies of the night is raised. “You never felt you were going to Patpong to meet prostitutes, you went to there to have a drink, enjoy your mates’ company and hopefully meet a nice girl. That’s the way it was and that’s how most regulars viewed it. “It was also a great place just to meet people from all kinds of backgrounds. I suppose back then it was the equivalent of being online today.” For Shrimp, now a married man and father of two boys, and many others of his era, Patpong’s special aura has gone, probably forever. He hasn’t been near the place for six months. So what caused its decline? The man who once epitomized Patpong’s fun and frivolity reckons it’s all down to the presence of the vendors plus the aggressive competition amongst the bars, which has made them less friendly than in the past. But that’s not all, he jokes. “The decline of Patpong began when I got married 15 years ago.” |

Tales of Bangkok Nightlife

Author Dean Barrett spent so much time in Patpong in the '60s, it’s a wonder he wasn’t charged rent. Here he reveals how the area has changed

APPLES. I had never realized the true value of apples until I arrived in Thailand with the Army Security Agency in March of 1966. I was quickly informed that Thais loved apples but because of the nature of Thai soil, or whatever, could not grow an apple worthy of the name. But our compound’s mess hall in the Saphankwai section of Bangkok had a profusion of imported apples stacked in bowls on many of the tables. Big, red, juicy, succulent apples. I remember the Thai waitresses in their crisp blue-and-white uniforms ogling them the same way I ogled the Thai waitresses. And as I quickly learned from fellow GIs a taxi ride from our Patiphat Road compound, where I was stationed, all the way down to Patpong Road was eight baht. Ten if you didn’t bargain well. Because there were no meters in taxis then and, monsoon rain or 100-Fahrenheit heat, bargaining with the driver was de rigueur.

However, most taxi drivers in those days would happily accept two apples in lieu of eight baht. Rumor-control Headquarters had it that among some military personnel at Seri Court apples even became a medium of exchange for other favors as well.

(I wouldn’t try the apple approach now as I suspect it might not work in 2010).

Seri Court GIs were not exactly the favorite customers of bar girls. Unlike excited, hormone-racing R&R GIs from Vietnam who partied mainly in the R&R bars on Petchaburi Tad Mai, we lived in Bangkok, were not pressed for time, and were in no hurry to part with our money. In fact, a few girls upon hearing we were from Seri Court were known to mutter terms of endearment, something like, “Number ten, cheap Charley, mai dee, Seri Court GI.” And for decency’s sake I have left out a few of the more colorful adjectives.

Ah, but the bargirls on Patpong were lovely nonetheless. And certainly by today’s Bangkok bar standards they were coy, diffident, demure – one might almost say – bashful. Most were dressed in modest street clothes and many could have passed as office workers. Some sported the beehive and other elaborate hairdos of the period. As far as decorum went, in the 1960’s no bargirl working in a Patpong bar ever groped me or dared place her hand on my private parts.

The girls worked in a particular bar but not on salary. They did have to abide by the rules of whatever bar they worked in such as hours of employment and what percentage of the drinks went to the bar, decorum when interacting with customers, etc. Their drinks were mainly of some non-alcoholic peppermint concoction and Singha beer was available

only in bottles, no cans.

Nightclubs for Thai men were mainly on Ratchadamnern Road and we seldom ventured there. But some of us did patronize the hi-so Thai nightclubs in our area such as the Café de Paris, Sani Chateau and Starlight. These had dance floors and Filipino bands. Here one paid for his time with the girl and for her (generally non-alcoholic) drinks, about 50 baht an hour, two-hour minimum, at a time when the baht was 20 to one. One of the singers recalled a sign behind the counter at Sani Chateau which read “check your values here.” There were, of course, the infamous Klong Toey dock area bars such as Venus and Mosquito, for sailors and locals and whoever dared venture in.

It was indeed a very different Bangkok: No go-go dancing, no Soi Cowboy and no Nana Plaza. And, of course, no phones! In the 60s no one had a cell phone and most houses had no phone at all. To have a phone in your house in those days you would have paid a lot of money, allegedly, above and below the table. And you were probably very well off indeed. I always love the look of horror on the faces of bargirls today when I explain that in those days no one had a phone. Their faces turn white and they look as if they are in shock. “No cell phone?” “No. I mean no phones at all!” I think the concept of a world without phones has never occurred to them and it is not something they wish to contemplate.

But Patpong in those days was still mainly a street of businesses such as airlines and restaurants, not a street crowded with bars. To get a glimpse of the colorful personalities around in those days - including the Thai founder of Patpong himself, Air America pilots, bar owners, strange customers, CIA types, police raids, and, of course, the working girls, etc. - try to get a copy of Alan Dawson’s excellent but long out-of-print Patpong: Bangkok’s Big Little Street. The names of so many of the famous and infamous bars of those days where friends and I cavorted are all in the book: Max’s Place, Bamboo Bar, Red Door, Chiquitas, Manos, Amor, Roma. And standing outside at least one of these bars I would find girls asking if they could accompany me in as no unescorted girls were allowed to enter. Such prim and proper times.

People often ask me, “Is Thailand better now?” The question of course is impossible to answer. Better for whom? Is it better for Thailand’s rich; Thailand’s poor; Thailand’s middle class?

Better for tourists? Better for farang residents? I cannot say it is “better” now. But I can say the nightlife experience is very different.

Obviously, Thais are no longer shocked by seeing foreign men and Thai women holding hands (and much more) in public. But the barfining now leads to an air-conditioned room or apartment much like it looks in the West. All rather nondescript, unremarkable, characterless, monotonous.

Contrast this with the Olde Days as I have described elsewhere: She escorts me to her rickety wooden shack on stilts over a malodorous muddy field. The cheap, pink, plastic fan doing little to cool the humid air but rhythmically swaying intricately spun spider webs as it passed through its cycle of jerky turns; the motionless wall lizards, patiently lying in wait for the fly or insect oblivious to the danger of their lightning fast tongues; the scent of spicy Thai food mixed with the putrescent odor of garbage and God knew what else in the miasmic mud beneath the shack; the shelf full of PX cosmetics and cartons of Salem previous G.I. boyfriends had bought for her; the newspaper cutouts of Thai movie stars imperfectly aligned along the wooden walls serving as the room’s decoration.

It is hard for anyone who was not there to realize what a flat city Bangkok was in those days. I believe in all of Bangkok there was one escalator and two elevators. Skyscrapers were still in the future and as I tell Thais today with only slight exaggeration, in those days the tallest structure in Bangkok was me. A friend and I even managed to find a klong-side, open-air shop which often allowed us to borrow a small, narrow craft and paddle in the klongs outside Bangkok; klongs which today have no doubt been filled in.

A sexy, amateurish and often inadvertently humorous cabaret show on Yaowarat Road known as the Fuji show was a favorite of Thai men in Chinatown. A fellow soldier at Seri Court, about to return to the States, whispered about it to me one night as if passing on a state secret to one carefully selected. He did not want the place flooded with foreigners. And, sure enough, in the nights I spent there, I was always the only farang. The atmosphere of high, pastel-striped ceiling, concrete walls, somewhat raunchy beer-drinking Thais and Thai-Chinese, cute but often inept dancers and surprisingly erotic shows would be difficult to describe but it was unique. And, yes, when I left Bangkok for Taipei in February of 1968, I did consider carefully the individual to whom I passed on its location.

From 1970 to 1986 I lived in Hong Kong and started a publishing company with several Thai clients, including Thai International and Sawasdee magazine. And so again I found myself spending a great deal of time in Bangkok and a willing participant in Bangkok’s nightlife. Now, the relations between the sexes were far more open, and the rage was go-go dancing.

Rick Menard, who passed away from cancer last year, had begun go-go dancing in Bangkok in 1969 at his Grand Prix bar. And dancers in places like the famous Mississippi Queen, Mike’s Place, Superstar, Butterfly, Grand Prix, Flying Machine, Memphis Bar, really did dance. Many were on a separate stage above the bar, dancing alone, and proud to show off their skills.

Today, with some notable exceptions, go-go dancing usually involves several girls on a stage doing nothing more than a bit of shuffling while chatting with the next dancer or observing herself in the mirror.

In the 70s and 80s the dancers wore bottoms big enough to add beaded slogans such as “Kiss”, “No”, and “Thank you.” Such outsized apparel would be hard to find in a go-go bar in 2010 where the skimpily dressed dancers are often habiliment-challenged.

From 1986 to 2000, I lived in New York City for 14 years and when in Asia traveled mainly to China. About a dozen years ago I came back to visit Bangkok for the first time in many years and immediately decided to make a nostalgic visit to the famous road I had known so well. This is an embarrassing revelation to make, especially from one who once practically lived on Patpong – I couldn’t find it. I wandered around the area and kept walking where I believed it was but all I could see was a street with tourist stalls and shops on both sides selling junk to tourists.

Then, when about to give up in despair, I spotted a sign across the road which said “Safari Bar” and I realized I was on Patpong but it had changed almost beyond recognition. Where once I could escort a bargirl into a samlor right outside her Patpong bar, the street was now closed off to traffic. And most of the bars I had known had been gutted and stocked with cheap wooden statues and knockoffs of famous brands.

Truth to tell, I seldom get to Patpong Road these days. When I do venture out it is usually to Soi 33 or Soi Cowboy or occasionally Nana Plaza. Although a night owl can still have a very good time there, the Patpong atmosphere – especially because of the tourist stalls – has changed dramatically. Still, whenever I pass through Patpong Road sometimes a girl or a sign or a bar jogs my memory. And I fondly remember a time long past when I was told by pretty bargirls, “You number one, GI!”

Today, whenever I tell a Thai person that I first came to Thailand in March of 1966, they always think for a second and then announce, “Oh, I wasn’t born yet.” I have heard this so many times that now I agree with them and say, “Yes, when I arrived in Thailand no Thais had been born yet; there were no Thais in Thailand – only American military.”

I believe Hemingway said something about how wonderful it was to be young in Paris. Believe me, being young in Bangkok in the 60s was without question the experience of a lifetime.

From 1970 to 1986 I lived in Hong Kong and started a publishing company with several Thai clients, including Thai International and Sawasdee magazine. And so again I found myself spending a great deal of time in Bangkok and a willing participant in Bangkok’s nightlife. Now, the relations between the sexes were far more open, and the rage was go-go dancing.

Rick Menard, who passed away from cancer last year, had begun go-go dancing in Bangkok in 1969 at his Grand Prix bar. And dancers in places like the famous Mississippi Queen, Mike’s Place, Superstar, Butterfly, Grand Prix, Flying Machine, Memphis Bar, really did dance. Many were on a separate stage above the bar, dancing alone, and proud to show off their skills.

Today, with some notable exceptions, go-go dancing usually involves several girls on a stage doing nothing more than a bit of shuffling while chatting with the next dancer or observing herself in the mirror.

In the 70s and 80s the dancers wore bottoms big enough to add beaded slogans such as “Kiss”, “No”, and “Thank you.” Such outsized apparel would be hard to find in a go-go bar in 2010 where the skimpily dressed dancers are often habiliment-challenged.

From 1986 to 2000, I lived in New York City for 14 years and when in Asia traveled mainly to China. About a dozen years ago I came back to visit Bangkok for the first time in many years and immediately decided to make a nostalgic visit to the famous road I had known so well. This is an embarrassing revelation to make, especially from one who once practically lived on Patpong – I couldn’t find it. I wandered around the area and kept walking where I believed it was but all I could see was a street with tourist stalls and shops on both sides selling junk to tourists.

Then, when about to give up in despair, I spotted a sign across the road which said “Safari Bar” and I realized I was on Patpong but it had changed almost beyond recognition. Where once I could escort a bargirl into a samlor right outside her Patpong bar, the street was now closed off to traffic. And most of the bars I had known had been gutted and stocked with cheap wooden statues and knockoffs of famous brands.

Truth to tell, I seldom get to Patpong Road these days. When I do venture out it is usually to Soi 33 or Soi Cowboy or occasionally Nana Plaza. Although a night owl can still have a very good time there, the Patpong atmosphere – especially because of the tourist stalls – has changed dramatically. Still, whenever I pass through Patpong Road sometimes a girl or a sign or a bar jogs my memory. And I fondly remember a time long past when I was told by pretty bargirls, “You number one, GI!”

Today, whenever I tell a Thai person that I first came to Thailand in March of 1966, they always think for a second and then announce, “Oh, I wasn’t born yet.” I have heard this so many times that now I agree with them and say, “Yes, when I arrived in Thailand no Thais had been born yet; there were no Thais in Thailand – only American military.”

I believe Hemingway said something about how wonderful it was to be young in Paris. Believe me, being young in Bangkok in the 60s was without question the experience of a lifetime.

Why Patpong in 1960 melted my 13-year-old heart

By Alex Mavro

A long-time Bangkok veteran recalls the street’s earliest pleasure: ice cream

WHILE I arrived in Bangkok before most, including unfortunately most Thais, I did not make a beeline for the street of infamy for a number of reasons.

First, being to the manner born meant that tawdriness was never next to manliness, in my world. (At least, that’s the way I remember it, and there are damn few around who can challenge my memory of the early 60s, doncha know?).

| Second, and I’m sure you’ve heard this before, Patpong then was nothing like Patpong now and even less like Patpong at its peak, which I would date to the early 70s. In fact, my first trips to Patpong were for ice cream, not entertainment. The source of the ice cream, Tip Top, is the only establishment that still exists from my earliest visits to The Street in 1960 as a lad of 13. That said, I did begin making regular trips to Patpong to satisfy a fetish of mine. No, not an ice cream fetish. I’ll let you try to guess what it was, before I tell you. To give you a bit of backdrop: Patpong was one single road in the early 60s. On it sat one of the better hotels in the city, a hotel in which my family and I stayed in 1957. (I don’t count that as a Patpong visit: we were actually living in Saigon and on vacation in Bangkok). The Plaza Hotel, it was, and a vestige of it remains to this day. It took up all of the building in which today it is a minor tenant. The space between the hotel – which faced on what is now Patpong II and featured a restaurant, the Thai Room, which remained in business until recently – and what is now Patpong I was a huge parking area that extended the length of the hotel building. Patpong itself was small, almost a cul-de-sac, with a steeply arched bridge at one end to cross the khlong that ran alongside Silom Road. It definitely was not a place you accidentally enountered. Most people who went there in the early 60s worked for or with the international airlines, whose not-so-many head offices migrated there: some remained well into the 70s. There was only a single eatery of note at the time, and that was Tip-Top, renowned for its desserts generally and ice creams, especially. Real ice cream – emphasis on cream – was exceedingly rare in mid-century Bangkok. My father and I (now 14) shared a sweet tooth that couldn’t begin to be sated by the sherbert-like imitations that were favored by many. So when the mood stuck, which was weekly, generally following a night out at the movies (most movie houses were in Chinatown), we would skip over to nearby Patpong for a chocolate ice cream sundae covered in thick chocolate sauce. Chocolate on chocolate: did I mention our family’s diabetes? |

I mentioned my father. He and I hung out together. We were buds. He had been neglected by his own father, and promised himself he would never treat a son of his with such disdain.

He may have overcompensated. Fearing the combination of temptation, availability, and youthful hormones, he reasoned that if I hung around with my schoolmates, trouble was a given. To cut it off at the pass, he decided that if trouble there must be, then at least he could arrange to be present when it happened.

So, wherever I went, so did he. And vice versa. And of course, we went out a lot at night.

There were no bars per se at the time. Nor were there massage parlors. The primary evening entertainment came in the form of modified dance halls, with “partners” available as company for an hourly rate – 40 baht, by the mid-sixties. Large beers were around 12 baht, mixed drinks 10 to 20. The exchange rate was 20 baht to the USD.

These places were pitch-black, with blackout curtains where there were windows. Waiters would shine a flashlight on the girls’ faces to allow you to make a selection. It was an environment I took to, naturally, but western visitors rarely shared my

enthusiasm.

Tea houses, mainly along lower Siphya Road, but also widely scattered around the city, formed the other main entertainment stream. (Apologies for addressing myself to male predilections. I have the disadvantage of never having experienced any other). Unlike “pooying partner,” who were in the geisha mold, tea house ladies were there for one purpose only, and the many small rooms that filled the nooks and crannies of these establishments gave it away.

While I wander somewhat from what began as a description of early Patpong, I believe it is important to understand the wider setting. Even then, Bangkok was a string of collected hamlets with no real downtown, and with a full complement of necessities (and not-so-necessities) in each hamlet. That included night clubs and tea houses and just plain ‘hotels’ that came fully equipped – wink, wink. Bangkok had no Las Vegas-style strip where nocturnal activities were concentrated.

In the early 60s, Patpong would’ve been the last place I would go for evening entertainment. The first joint on the street, by my memory, was an after dinner piano bar featuring Narcing Aguilar. (Don’t ask me the name of the place: maybe one of our readers can help me out).

Most of us began the evening at the Luna Club on the corner of Sukhumvit Soi 7, or the Paradise Club, near Gaysorn, about where Big C is today, or the Sani Chateau, in Gaysorn, where the hourly charge began at 100 baht but featured your choice of companion nationality – Chinese, French, Russian, and more. There was the popular Lolita and the inimitable Moulin Rouge over on Rajadamnern Avenue: see what I mean about scattered?

These were by no means the full extent of the night life, but what’s noticeable is that Patpong didn’t even register. Max’s, which opened at the Suriwong end of Patpong around 1962, originally served airline crew but as time went on became the hang-out for the Air America crowd.

Unfortunately, my own Patpong experience was interrupted by my deportation to the USA for five years of Americanization. (It didn’t take). I returned on New Years’ Day, 1972, to find a very different Street, indeed. Now the bridge over Khlong Silom was gone (as was the Khlong) and there were wall-to-wall bars on both sides of the road, gradually squeezing out the first-growth airline offices, including (eventually) the Pan Am and JAL buildings that had sprung up in the parking lot of the Plaza Hotel.

Although I was working upcountry, 1972-1977, my experience of Patpong during those years was all the more intense for its episodic nature. Fortunately, several other equally n’eer-do-well contributors were present and accounted for, by then, and can fill in many of the gaps for you.

Except one: unless you were there at the time, it would be impossible to guess why I went to Patpong once or twice a week between 1960 and 1964: Because that is where the USIS library was, at the time. You entered about where the Safari Bar is, today. The USIS library was the only library in town worthy of the name and certainly the only English language library in the Kingdom. (It has since morphed into the AUA library on

Rajadamri). As a mad reader, I made it my personal haven until

I went to work in Laos.

But that’s a different story.

Alex’s family moved to Southeast Asia in the wake of Dien Bien Phu, in April of 1955, when he celebrated his first Songkran in Thailand as an eight-year old. His father was with USOM. Alex graduated with the ISB class of 1964, then worked a year in Laos before being Shanghai’d to Gainesville, Florida, for American training. He has lived in Thailand ever since.

He may have overcompensated. Fearing the combination of temptation, availability, and youthful hormones, he reasoned that if I hung around with my schoolmates, trouble was a given. To cut it off at the pass, he decided that if trouble there must be, then at least he could arrange to be present when it happened.

So, wherever I went, so did he. And vice versa. And of course, we went out a lot at night.

There were no bars per se at the time. Nor were there massage parlors. The primary evening entertainment came in the form of modified dance halls, with “partners” available as company for an hourly rate – 40 baht, by the mid-sixties. Large beers were around 12 baht, mixed drinks 10 to 20. The exchange rate was 20 baht to the USD.

These places were pitch-black, with blackout curtains where there were windows. Waiters would shine a flashlight on the girls’ faces to allow you to make a selection. It was an environment I took to, naturally, but western visitors rarely shared my

enthusiasm.

Tea houses, mainly along lower Siphya Road, but also widely scattered around the city, formed the other main entertainment stream. (Apologies for addressing myself to male predilections. I have the disadvantage of never having experienced any other). Unlike “pooying partner,” who were in the geisha mold, tea house ladies were there for one purpose only, and the many small rooms that filled the nooks and crannies of these establishments gave it away.

While I wander somewhat from what began as a description of early Patpong, I believe it is important to understand the wider setting. Even then, Bangkok was a string of collected hamlets with no real downtown, and with a full complement of necessities (and not-so-necessities) in each hamlet. That included night clubs and tea houses and just plain ‘hotels’ that came fully equipped – wink, wink. Bangkok had no Las Vegas-style strip where nocturnal activities were concentrated.

In the early 60s, Patpong would’ve been the last place I would go for evening entertainment. The first joint on the street, by my memory, was an after dinner piano bar featuring Narcing Aguilar. (Don’t ask me the name of the place: maybe one of our readers can help me out).

Most of us began the evening at the Luna Club on the corner of Sukhumvit Soi 7, or the Paradise Club, near Gaysorn, about where Big C is today, or the Sani Chateau, in Gaysorn, where the hourly charge began at 100 baht but featured your choice of companion nationality – Chinese, French, Russian, and more. There was the popular Lolita and the inimitable Moulin Rouge over on Rajadamnern Avenue: see what I mean about scattered?

These were by no means the full extent of the night life, but what’s noticeable is that Patpong didn’t even register. Max’s, which opened at the Suriwong end of Patpong around 1962, originally served airline crew but as time went on became the hang-out for the Air America crowd.

Unfortunately, my own Patpong experience was interrupted by my deportation to the USA for five years of Americanization. (It didn’t take). I returned on New Years’ Day, 1972, to find a very different Street, indeed. Now the bridge over Khlong Silom was gone (as was the Khlong) and there were wall-to-wall bars on both sides of the road, gradually squeezing out the first-growth airline offices, including (eventually) the Pan Am and JAL buildings that had sprung up in the parking lot of the Plaza Hotel.

Although I was working upcountry, 1972-1977, my experience of Patpong during those years was all the more intense for its episodic nature. Fortunately, several other equally n’eer-do-well contributors were present and accounted for, by then, and can fill in many of the gaps for you.

Except one: unless you were there at the time, it would be impossible to guess why I went to Patpong once or twice a week between 1960 and 1964: Because that is where the USIS library was, at the time. You entered about where the Safari Bar is, today. The USIS library was the only library in town worthy of the name and certainly the only English language library in the Kingdom. (It has since morphed into the AUA library on

Rajadamri). As a mad reader, I made it my personal haven until

I went to work in Laos.

But that’s a different story.

Alex’s family moved to Southeast Asia in the wake of Dien Bien Phu, in April of 1955, when he celebrated his first Songkran in Thailand as an eight-year old. His father was with USOM. Alex graduated with the ISB class of 1964, then worked a year in Laos before being Shanghai’d to Gainesville, Florida, for American training. He has lived in Thailand ever since.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed