Veteran correspondent Maxmilian Wechsler recalls some of his most interesting and exclusive assignments from the past two decades. The articles, originally published in Thailand, have been edited for clarity.

FROM THE YEAR 2004

FM José Ramos-Horta gives his views on a wide range of regional issues.

The already good relations between Thailand and East Timor were given a welcome boost last Sunday, when the son of East Timorese Foreign Minister José Ramos-Horta, Moubere Lorosa’e de Silva-Horta, married longtime Thai girlfriend Soraya Simsiri in Bangkok. Photos of the married couple were on the front pages of Thai-language newspapers, and the young nation with a population of one million was once again in the news.

Roughly the size of Fiji, East Timor went through a long struggle for independence which saw many of its political leaders, including Mr Ramos- Horta, exiled from their homeland. Prior to the historic general election on August 30, 2001, Thai troops were sent to East Timor as part of the United Nations peace-keeping force which was later replaced by the UN Transitional Administration for East Timor (UNTAET).

At midnight on May 19, 2002, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan handed the government over to Presidentelect Xanana Gusmão and East Timor became the world’s 192nd nation. On September 27 of the same year, East Timor joined the UN, becoming its 191st member.

Since then Mr Ramos-Horta has been a frequent visitor to Bangkok, where he’s attended international meetings and met many of his Thai friends. His work on behalf of the East Timorese people earned him the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize, which he shared with Bishop Belo.

FM José Ramos-Horta gives his views on a wide range of regional issues.

The already good relations between Thailand and East Timor were given a welcome boost last Sunday, when the son of East Timorese Foreign Minister José Ramos-Horta, Moubere Lorosa’e de Silva-Horta, married longtime Thai girlfriend Soraya Simsiri in Bangkok. Photos of the married couple were on the front pages of Thai-language newspapers, and the young nation with a population of one million was once again in the news.

Roughly the size of Fiji, East Timor went through a long struggle for independence which saw many of its political leaders, including Mr Ramos- Horta, exiled from their homeland. Prior to the historic general election on August 30, 2001, Thai troops were sent to East Timor as part of the United Nations peace-keeping force which was later replaced by the UN Transitional Administration for East Timor (UNTAET).

At midnight on May 19, 2002, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan handed the government over to Presidentelect Xanana Gusmão and East Timor became the world’s 192nd nation. On September 27 of the same year, East Timor joined the UN, becoming its 191st member.

Since then Mr Ramos-Horta has been a frequent visitor to Bangkok, where he’s attended international meetings and met many of his Thai friends. His work on behalf of the East Timorese people earned him the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize, which he shared with Bishop Belo.

| The following contains edited extracts from an exclusive interview with the 55-year-old foreign minister, including the problems facing his country: “From the humanitarian side, it is severe malnutrition. Poverty is partly to blame, but we also cannot produce enough food to feed our people. We are still a least developed country. Malaria and tuberculosis are rampant. Unemployment is around 20 percent. This is high but not so bad for a country which has been independent for only two years. “In 1999, unemployment was between 60 and 70 percent. So, it went down dramatically, particularly because of the tremendous growth in the agricultural and small business sectors. “We have had considerable international assistance from many countries, including Australia, the European Union, Japan, New Zealand, the Nordic countries, Portugal, the United Kingdom and the United States. We receive a lot of help from inter-governmental agencies, foundations, NGOs and individuals– with hundreds of volunteers from Portugal and Australia. |

“A well-known Hong Kong philanthropist, Eric Hotung, has been a big help. He bought a ship, an old Australian Navy hospital that cost him US$700,000, and converted it into a cargo-passenger ship. It took Timorese refugees from Indonesia to East Timor for two years, at the cost of about US$80,000-100,000 a month.

He also helped to refurbish the airport terminal in Dili. And he is not the only one. There are many people like him. “Despite 25 years of conflict, there is a lot of positive sentiment of East Timorese people towards Indonesia and vice-versa. The Indonesian government has also been very constructive and pragmatic in dealing with East Timor as an independent country.

“There’s no Thai investment in East Timor as yet. But Thailand has been one of East Timor’s best friends in the region. Other ASEAN nations like the Philippines and Singapore are also big contributors.

“Thailand, I think, is the leading producer of canned fish, and today you don’t find much fish in the Thai waters. Their fishing fleets must go elsewhere. East Timor has enormous fishery resources. There is a strong interest in the Thai fishery industry in having access to our waters.

“We are not yet ready to be a member of ASEAN and it won’t happen before five to six years.

However, we have made the strategic policy decision to join the grouping.

“The Nobel Peace Prize was the most important development in our struggle because it increased the international visibility of East Timor while imposing a high diplomatic cost on Indonesia over its occupation of our country.”

Regarding his earlier ban on entering Thailand, Mr Ramos-Horta said: “Well, a few years ago when circumstances were different, anyone who was involved in the East Timorese struggle wasn’t welcome in any Asian country because of the Indonesian influence. This is understandable.

“However, I came here during that time and received a lot of publicity. This upset Indonesia, who put pressure on Thailand, and I was not allowed to enter afterwards. The same happened to me in the Philippines, which organised a big international conference in 1994 that I was banned from attending. This was very embarrassing not just for the Philippines but for Indonesia as well, because by attempting to stop me from attending the conference they created a situation that led to favourable publicity for us.

“My son and his bride met at Sydney University, where they both studied. He studied Public Administration while she studied Business Administration. I didn’t believe at that time that he was serious about wanting to get married. But I am an extremely liberal father. I deal with my son like a brother or a friend.

“They will most likely live in East Timor. He will go to Honolulu to continue his Strategic Defense studies. After that, he will probably go to the UK or US to continue the defense studies. After completion of his studies, he will work in our defense department. My son has a very deep appreciation and sensitivity for Thailand and for the Asian culture. He will be a good friend of Thailand in the future.”

He also helped to refurbish the airport terminal in Dili. And he is not the only one. There are many people like him. “Despite 25 years of conflict, there is a lot of positive sentiment of East Timorese people towards Indonesia and vice-versa. The Indonesian government has also been very constructive and pragmatic in dealing with East Timor as an independent country.

“There’s no Thai investment in East Timor as yet. But Thailand has been one of East Timor’s best friends in the region. Other ASEAN nations like the Philippines and Singapore are also big contributors.

“Thailand, I think, is the leading producer of canned fish, and today you don’t find much fish in the Thai waters. Their fishing fleets must go elsewhere. East Timor has enormous fishery resources. There is a strong interest in the Thai fishery industry in having access to our waters.

“We are not yet ready to be a member of ASEAN and it won’t happen before five to six years.

However, we have made the strategic policy decision to join the grouping.

“The Nobel Peace Prize was the most important development in our struggle because it increased the international visibility of East Timor while imposing a high diplomatic cost on Indonesia over its occupation of our country.”

Regarding his earlier ban on entering Thailand, Mr Ramos-Horta said: “Well, a few years ago when circumstances were different, anyone who was involved in the East Timorese struggle wasn’t welcome in any Asian country because of the Indonesian influence. This is understandable.

“However, I came here during that time and received a lot of publicity. This upset Indonesia, who put pressure on Thailand, and I was not allowed to enter afterwards. The same happened to me in the Philippines, which organised a big international conference in 1994 that I was banned from attending. This was very embarrassing not just for the Philippines but for Indonesia as well, because by attempting to stop me from attending the conference they created a situation that led to favourable publicity for us.

“My son and his bride met at Sydney University, where they both studied. He studied Public Administration while she studied Business Administration. I didn’t believe at that time that he was serious about wanting to get married. But I am an extremely liberal father. I deal with my son like a brother or a friend.

“They will most likely live in East Timor. He will go to Honolulu to continue his Strategic Defense studies. After that, he will probably go to the UK or US to continue the defense studies. After completion of his studies, he will work in our defense department. My son has a very deep appreciation and sensitivity for Thailand and for the Asian culture. He will be a good friend of Thailand in the future.”

Behind the story:

Despite Mr Ramos-Horta’s busy schedule, I was able to secure an interview with him through a Thai contact. I couldn’t wait to meet this well-known global personality. It is not every day you interview a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

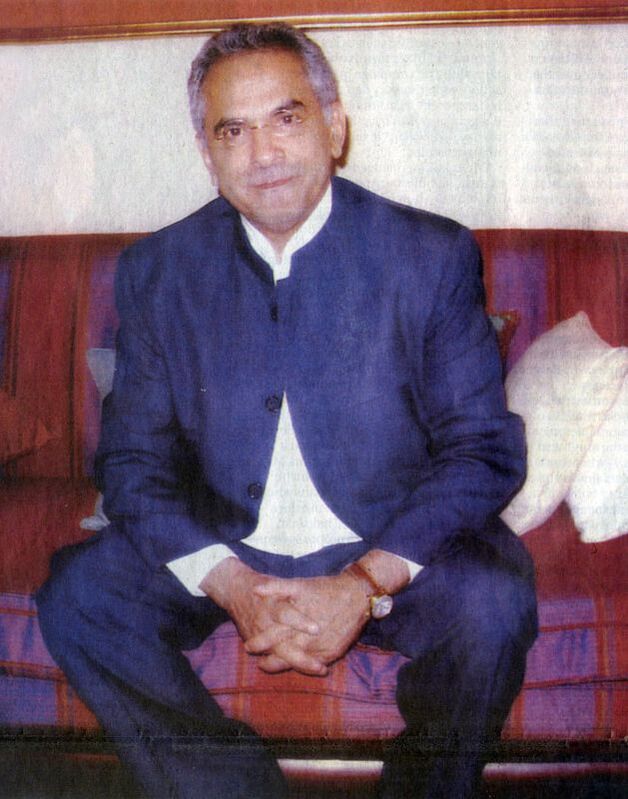

We met in his suite at the Sofitel Central Plaza Hotel (now Centara Grand Central Plaza Ladprao), where he sat on a sofa wearing a blue collarless jacket.

Mr Ramos-Horta gave me 45 minutes of his precious time. I was told later that his staff – who stood a little out of earshot – were wondering what we were talking about for so long. I hadn’t submitted a list of questions in advance and wasn’t asked for one. Mr Ramos-Horta is an effective politician and a gifted speaker. Talking to him was an unforgettable experience for me, and even after 15 years I still vividly remember the meeting.

Despite Mr Ramos-Horta’s busy schedule, I was able to secure an interview with him through a Thai contact. I couldn’t wait to meet this well-known global personality. It is not every day you interview a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

We met in his suite at the Sofitel Central Plaza Hotel (now Centara Grand Central Plaza Ladprao), where he sat on a sofa wearing a blue collarless jacket.

Mr Ramos-Horta gave me 45 minutes of his precious time. I was told later that his staff – who stood a little out of earshot – were wondering what we were talking about for so long. I hadn’t submitted a list of questions in advance and wasn’t asked for one. Mr Ramos-Horta is an effective politician and a gifted speaker. Talking to him was an unforgettable experience for me, and even after 15 years I still vividly remember the meeting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed