Veteran correspondent Maxmilian Wechsler recalls some of his most exciting – and dangerous – assignments from the past two decades

Beginning this month, The BigChilli is publishing selected full articles and excerpts from the more than 500 feature stories penned by longtime expat Maxmilian Wechsler over the past 20 years for English-language publications. Max will also offer his current thoughts and reflections on the articles.

“It was never my intention or desire to become a journalist, notwithstanding the first short news article I had published in 1966 in Pochoden (Torch), a newspaper put out by the Škoda factory in Plzen, in my native Czechoslovakia. I continued to write as a hobby, but had nothing else published until the year 2000. In between there was a lot to keep me occupied, including working for the Thai government (1976-2007), and in the mid-1980s opening a law office in Bangkok.

“At some point I realized that my life and work experiences and the connections I had made along the way had given me a unique perspective on my adopted country. So, after leaving the firm in 2000, I decided I would write stories more or less as a public service. My aim was and still is to present readers with true and unbiased information, backed by evidence whenever possible.

“From 2000 until 2006 I wrote a total of 66 articles for The New Era Journal, a newspaper formerly published in Bangkok by Myanmar exiles. In 2003 I began writing for Bangkok Post Sunday editions, contributing more than 200 stories before leaving in 2011 to write for The BigChilli. This makes article number 279 for the magazine.”

“It was never my intention or desire to become a journalist, notwithstanding the first short news article I had published in 1966 in Pochoden (Torch), a newspaper put out by the Škoda factory in Plzen, in my native Czechoslovakia. I continued to write as a hobby, but had nothing else published until the year 2000. In between there was a lot to keep me occupied, including working for the Thai government (1976-2007), and in the mid-1980s opening a law office in Bangkok.

“At some point I realized that my life and work experiences and the connections I had made along the way had given me a unique perspective on my adopted country. So, after leaving the firm in 2000, I decided I would write stories more or less as a public service. My aim was and still is to present readers with true and unbiased information, backed by evidence whenever possible.

“From 2000 until 2006 I wrote a total of 66 articles for The New Era Journal, a newspaper formerly published in Bangkok by Myanmar exiles. In 2003 I began writing for Bangkok Post Sunday editions, contributing more than 200 stories before leaving in 2011 to write for The BigChilli. This makes article number 279 for the magazine.”

Myanmar exiles everywhere

“Most of my early articles concerned Myanmar, commonly called Burma, where armed ethnic groups were and, in some cases, still are involved in a lethal struggle with the ruling regime, at that time called the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

“A lot of the action actually took place in Thailand, which became a refuge for thousands of exiles. Some major armed ethnic militias were based on or very close to the Thai border. Dozens of exile-led political, women’s rights, human rights, civil society, media and other types of organizations were based in Thailand, as were a number of NGOs established to assist the refugee community.

“Thailand’s proximity to Myanmar also attracted foreign intelligence agencies; some NGOs worked closely with them, passing on all kinds of intelligence obtained from exiles. For example, groups inside Myanmar like the Karen National Union (KNU) and its armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), had the capability to intercept Myanmar Army communications and could give information on troop movements. Some exiles were double or eventriple agents.

“There were sizable exile communities in Bangkok, Mae Sot, Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, Mae Sariang, Sangkhlaburi and other locations throughout Thailand. Some exiles made frequent trips across the border for various reasons.

“My association with Myanmar exiles in Thailand began in early 1998, when I was introduced to U Tin Maung Win, one of the top executives of the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB), an alliance of 22 antigovernment groups. He introduced me to other top exile leaders and important members, and invited me to attend the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the DAB’s formation held in Chiang Mai on October 10, 1998.

“In those days it was a challenge for journalists to distinguish between the exiles genuinely working for a better day in Myanmar and the opportunists and criminals, and to shake out the truth from the lies and deception. It took me some time to find out ‘who was who’, and if I had known then what I know today I would in many cases have selected different words for my stories, starting with the headlines.

“Nevertheless, the articles below are presented in their original form except for small editing changes made for clarity. Some photos in thisarticle have never been published.”

“A lot of the action actually took place in Thailand, which became a refuge for thousands of exiles. Some major armed ethnic militias were based on or very close to the Thai border. Dozens of exile-led political, women’s rights, human rights, civil society, media and other types of organizations were based in Thailand, as were a number of NGOs established to assist the refugee community.

“Thailand’s proximity to Myanmar also attracted foreign intelligence agencies; some NGOs worked closely with them, passing on all kinds of intelligence obtained from exiles. For example, groups inside Myanmar like the Karen National Union (KNU) and its armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), had the capability to intercept Myanmar Army communications and could give information on troop movements. Some exiles were double or eventriple agents.

“There were sizable exile communities in Bangkok, Mae Sot, Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, Mae Sariang, Sangkhlaburi and other locations throughout Thailand. Some exiles made frequent trips across the border for various reasons.

“My association with Myanmar exiles in Thailand began in early 1998, when I was introduced to U Tin Maung Win, one of the top executives of the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB), an alliance of 22 antigovernment groups. He introduced me to other top exile leaders and important members, and invited me to attend the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the DAB’s formation held in Chiang Mai on October 10, 1998.

“In those days it was a challenge for journalists to distinguish between the exiles genuinely working for a better day in Myanmar and the opportunists and criminals, and to shake out the truth from the lies and deception. It took me some time to find out ‘who was who’, and if I had known then what I know today I would in many cases have selected different words for my stories, starting with the headlines.

“Nevertheless, the articles below are presented in their original form except for small editing changes made for clarity. Some photos in thisarticle have never been published.”

All articles written in year 2000 -Maha Sang: Man of his people? Or drug runner?

Excerpts:

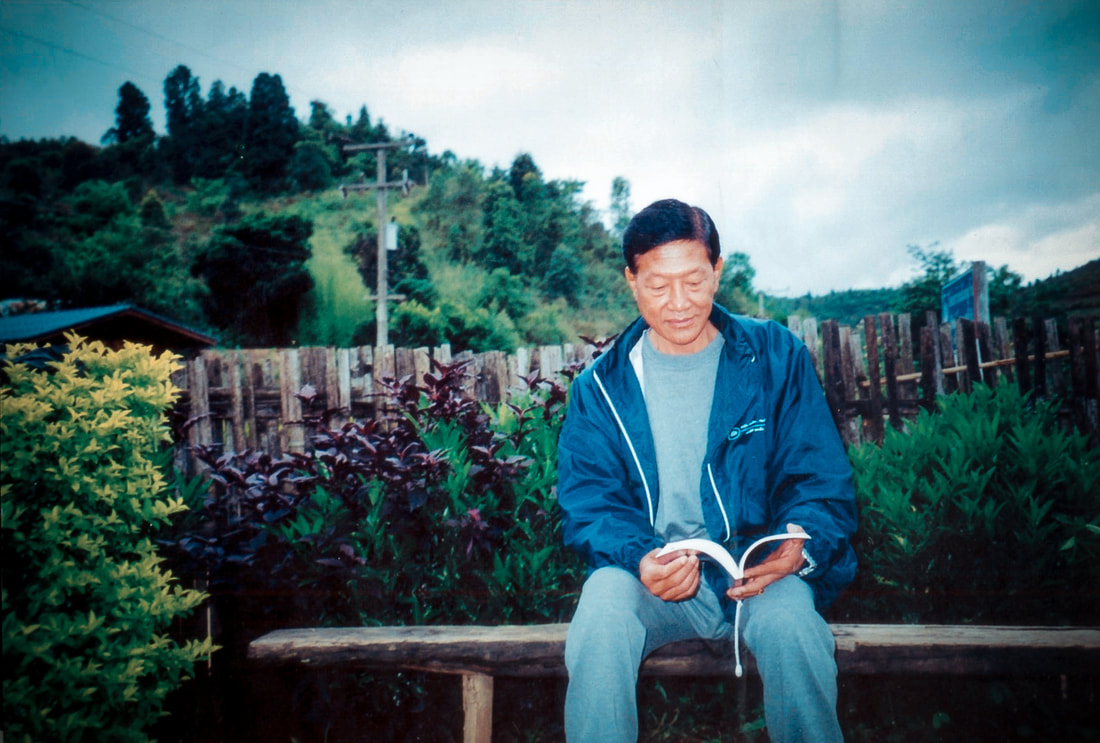

The picturesque valley of Mae Aw (Ban Rak Thai) village in Mae Hong Son province is the home of legendary opposition revolutionary Wa leader Maha Sang.

A son of the Prince of Veang Xing of Wa State, Maha Sang has devoted most of his life to the fight against oppression, for a free Wa people and for a democratic Myanmar. He began his struggle in the 1960s.

Maha Sang is now 54 years old and has lived for decades in a modest wooden house surrounded by hillsnear Mae Aw in Mae Hong Song province. The small village, founded by nationalist Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) fleeing communist Chinese forces, is just a stone’s throw from the Myanmar border. In fact, SPDC soldiers could easily see his house if they dared come so close.

The apparent tranquility of Mae Aw is deceiving. The surrounding hills are mined and treacherous. The SPDC troops and the Wa National Army (WNA) commanded by Maha Sang face each other. “It is a mouse and cat game,” Maha Sang pointed out.

Maha Sang is also the chairman of the Wa National Organization (WNO).The WNA is its armed wing. He commands several hundred well disciplined and professionally trained soldiers based inside Myanmar. Maha Sang also holds the post of vice-chairman of the National Democratic Front (NDF) and until recently was chairman of its narcotics suppression department. The NDF has formed a new anti-narcotics committee headed by Rimond Htoo from the Karenni National Progressive Party. Maha Sang’s expertise in drug suppression and his experience will be avaluable contributor to the committee.

Maha Sang has often been accused by the Thai press of being involved in drug-related activities.

He vehemently refutes these allegations, blaming a foreign country for orchestrating a campaign against him. “If I was involved in drug dealing the Thais wouldn’t allow me to stay here,” Maha Sang explained in the tone that made his argument convincing.

“About two years ago Lt Colonel Sann Pwint, an official of the SPDC Military Intelligence came to see me at Mae Aw, to pressure me in to surrender. But since we refused they have increased military pressure on us,” Maha Sang added.

A permanent Thai Border Patrol Police (BPP) checkpoint is located on the main road just a few meters from Maha Sang’s house, staffed with several Thai policemen. Maha Sang’s cooperation with the Thai authorities has been excellent and they are on very friendly terms. Both parties undisputedly benefit. Only a couple of years ago Mae Aw was no man’s land, but since the Thai government built a new asphalt road it has become a popular tourist spot. The cooperation between the Thai authorities and Maha Sang returns dividends.

Maha Sang is a friendly, hospitable, soft-spoken Wa leader. He’s constantly watched by his men. The border is too close and one can never be careful enough as enemy agents could always sneak in under cover of the night.

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) leaders are well aware of his antidrug activities and they hate him and wouldn’t mind to have him eliminated. He explained in well-spoken Thai language that all his support comes from ‘his people’ who live in

surrounding villages all around Mae Hong Son province. Everybody respects his devotion to the cause and treats him as their ‘Prince.’ Maha Sang devotes all his time to fight the SPDC and to reduce the drug menace.

He pointed to his roof and said: “I fought the Mong Tai Army (MTA) led by the drug warlord Khun Sa 10 years ago. Just look at that roof riddled with many holes. The MTA soldiers fired their machine at my house from the hills. Luckily nobody was hurt. The MTA soldiers were everywhere at that time.”

Sipping Chinese tea, Maha Sang continued: “Whenever the Thai or foreign press mentions the name Wa, it is always connected to some illegal activities, mostly narcotics dealing. The press always describes the Wa people as outcasts, criminals and drug traffickers. This is totally false! Not all the Wa are involved in criminal activities. The Wa are peace-loving and hardworking people who, same as other ethnic groups, want to live in a free, democratic and peaceful country. Most of the Wa people, including the UWSA, despise the SPDC.”

Maha Sang continuously urges the UWSA and other groups to stop production of drugs and find other sources of income which will not harm people in Thailand and abroad! Many listen to him. He says he doesn’t have any grudge against people who criticize him. “That’s how democracy should work. We should all be brothers fighting together with our common enemy, the SPDC,” Maha Sang said.

The picturesque valley of Mae Aw (Ban Rak Thai) village in Mae Hong Son province is the home of legendary opposition revolutionary Wa leader Maha Sang.

A son of the Prince of Veang Xing of Wa State, Maha Sang has devoted most of his life to the fight against oppression, for a free Wa people and for a democratic Myanmar. He began his struggle in the 1960s.

Maha Sang is now 54 years old and has lived for decades in a modest wooden house surrounded by hillsnear Mae Aw in Mae Hong Song province. The small village, founded by nationalist Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) fleeing communist Chinese forces, is just a stone’s throw from the Myanmar border. In fact, SPDC soldiers could easily see his house if they dared come so close.

The apparent tranquility of Mae Aw is deceiving. The surrounding hills are mined and treacherous. The SPDC troops and the Wa National Army (WNA) commanded by Maha Sang face each other. “It is a mouse and cat game,” Maha Sang pointed out.

Maha Sang is also the chairman of the Wa National Organization (WNO).The WNA is its armed wing. He commands several hundred well disciplined and professionally trained soldiers based inside Myanmar. Maha Sang also holds the post of vice-chairman of the National Democratic Front (NDF) and until recently was chairman of its narcotics suppression department. The NDF has formed a new anti-narcotics committee headed by Rimond Htoo from the Karenni National Progressive Party. Maha Sang’s expertise in drug suppression and his experience will be avaluable contributor to the committee.

Maha Sang has often been accused by the Thai press of being involved in drug-related activities.

He vehemently refutes these allegations, blaming a foreign country for orchestrating a campaign against him. “If I was involved in drug dealing the Thais wouldn’t allow me to stay here,” Maha Sang explained in the tone that made his argument convincing.

“About two years ago Lt Colonel Sann Pwint, an official of the SPDC Military Intelligence came to see me at Mae Aw, to pressure me in to surrender. But since we refused they have increased military pressure on us,” Maha Sang added.

A permanent Thai Border Patrol Police (BPP) checkpoint is located on the main road just a few meters from Maha Sang’s house, staffed with several Thai policemen. Maha Sang’s cooperation with the Thai authorities has been excellent and they are on very friendly terms. Both parties undisputedly benefit. Only a couple of years ago Mae Aw was no man’s land, but since the Thai government built a new asphalt road it has become a popular tourist spot. The cooperation between the Thai authorities and Maha Sang returns dividends.

Maha Sang is a friendly, hospitable, soft-spoken Wa leader. He’s constantly watched by his men. The border is too close and one can never be careful enough as enemy agents could always sneak in under cover of the night.

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) leaders are well aware of his antidrug activities and they hate him and wouldn’t mind to have him eliminated. He explained in well-spoken Thai language that all his support comes from ‘his people’ who live in

surrounding villages all around Mae Hong Son province. Everybody respects his devotion to the cause and treats him as their ‘Prince.’ Maha Sang devotes all his time to fight the SPDC and to reduce the drug menace.

He pointed to his roof and said: “I fought the Mong Tai Army (MTA) led by the drug warlord Khun Sa 10 years ago. Just look at that roof riddled with many holes. The MTA soldiers fired their machine at my house from the hills. Luckily nobody was hurt. The MTA soldiers were everywhere at that time.”

Sipping Chinese tea, Maha Sang continued: “Whenever the Thai or foreign press mentions the name Wa, it is always connected to some illegal activities, mostly narcotics dealing. The press always describes the Wa people as outcasts, criminals and drug traffickers. This is totally false! Not all the Wa are involved in criminal activities. The Wa are peace-loving and hardworking people who, same as other ethnic groups, want to live in a free, democratic and peaceful country. Most of the Wa people, including the UWSA, despise the SPDC.”

Maha Sang continuously urges the UWSA and other groups to stop production of drugs and find other sources of income which will not harm people in Thailand and abroad! Many listen to him. He says he doesn’t have any grudge against people who criticize him. “That’s how democracy should work. We should all be brothers fighting together with our common enemy, the SPDC,” Maha Sang said.

Behind the story:

My meeting with Maha Sang was arranged by a Shan exile and required a long drive from Bangkok to Mae Hong Son and then to Mae Aw (Ban Rak Thai) village. After leaving thebusy main highway for Mae Aw I drove around 30 kilometers on a two-lane, smooth, asphalt road, encountering only a handful of cars and motorcycles on the way. Just before Mae Aw was a checkpoint minded by BPP men; they lifted the barrier without checking me or the vehicle.

Maha Sang’s man waited near the barrier and pointed the way to his boss’s house not far away. He waited with several bodyguards and an interpreter who spoke perfect English. Next to Maha Sang was large oxygen tank and a small briefcase holding an oxygen bottle he takes with him when travelling. He was suffering from asthma and it was quite serious.

Most of the small houses in the village were nicely painted and in good condition and pickup trucks could be seen parked near some of them. Several large satellite dishes were visible. Maha Sang said that these were for telephones so the locals to talk to people in other KMT villages and relatives and friends in Taiwan. All this only a few hundred meters from the Myanmar border. It was obvious the residents were doing well but their means of making a living weren’t clear.

Maha Sang said off record that he often walked across the border to meet his soldiers, who sometimes joined with Myanmar soldiers for a chat and drink. I thought they were the enemy…

A few years later, I was told by someone close to Maha Sang that he and his soldiers controlled everything in Mae Aw and surrounding KMT villages. To illustrate his power and influence, this person said that Maha Sang had accidentally run over and killed a child while reversing a pickup. No one dared report the accident to the Thai authorities for fear of a reprisal.

An article published by Irrawaddy online on October 30, 2007 reported that Maha Sang died at Nakornping Hospital in Chiang Mai that day at the age of 61. He had been suffering from chronic lung disease and hospitalized since mid-October.

The article also said that Mae Hong Son Provincial Court approved arrest warrants for Maha Sang and his brother Maha Ja in February 2005, following accusations of involvement in producing and smuggling drugs into Thailand. Maha Sang was arrested in April 2005 and jailed in Chiang Mai until he became so ill he was transferred to the hospital.

“Maha Sang lived in Mae Hong Song for the past 20 years, after being pushed out of the inner circle of the opium trade. He previously worked with the UWSA Army commander Wei Hsueh Kang, who was widely suspected of being involved in the drug trade,” the article concluded.

My meeting with Maha Sang was arranged by a Shan exile and required a long drive from Bangkok to Mae Hong Son and then to Mae Aw (Ban Rak Thai) village. After leaving thebusy main highway for Mae Aw I drove around 30 kilometers on a two-lane, smooth, asphalt road, encountering only a handful of cars and motorcycles on the way. Just before Mae Aw was a checkpoint minded by BPP men; they lifted the barrier without checking me or the vehicle.

Maha Sang’s man waited near the barrier and pointed the way to his boss’s house not far away. He waited with several bodyguards and an interpreter who spoke perfect English. Next to Maha Sang was large oxygen tank and a small briefcase holding an oxygen bottle he takes with him when travelling. He was suffering from asthma and it was quite serious.

Most of the small houses in the village were nicely painted and in good condition and pickup trucks could be seen parked near some of them. Several large satellite dishes were visible. Maha Sang said that these were for telephones so the locals to talk to people in other KMT villages and relatives and friends in Taiwan. All this only a few hundred meters from the Myanmar border. It was obvious the residents were doing well but their means of making a living weren’t clear.

Maha Sang said off record that he often walked across the border to meet his soldiers, who sometimes joined with Myanmar soldiers for a chat and drink. I thought they were the enemy…

A few years later, I was told by someone close to Maha Sang that he and his soldiers controlled everything in Mae Aw and surrounding KMT villages. To illustrate his power and influence, this person said that Maha Sang had accidentally run over and killed a child while reversing a pickup. No one dared report the accident to the Thai authorities for fear of a reprisal.

An article published by Irrawaddy online on October 30, 2007 reported that Maha Sang died at Nakornping Hospital in Chiang Mai that day at the age of 61. He had been suffering from chronic lung disease and hospitalized since mid-October.

The article also said that Mae Hong Son Provincial Court approved arrest warrants for Maha Sang and his brother Maha Ja in February 2005, following accusations of involvement in producing and smuggling drugs into Thailand. Maha Sang was arrested in April 2005 and jailed in Chiang Mai until he became so ill he was transferred to the hospital.

“Maha Sang lived in Mae Hong Song for the past 20 years, after being pushed out of the inner circle of the opium trade. He previously worked with the UWSA Army commander Wei Hsueh Kang, who was widely suspected of being involved in the drug trade,” the article concluded.

Siege of Myanmar embassy –one year later and questions that remain unanswered

| Full article: On October 1, 1999, the Vigorous Myanmar Student Warriors (VBSW) seized the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok and took hostages. The drama ended the next day. All hostages were freed and the VBSW gunmen were flown by helicopter to the base of the socalled God’s Army, an armed ethnic Karen Christian group that used guerrilla warfare tactics against the SPDC army. Exactly one year later the vast majority of the Myanmar dissident leaders agreed that the embassy siege was a major setback for the whole opposition movement, as the sentiment of the Thai government and population had turned against them. The US State Department issued a strongly worded statement deploring the siege. Only one foreign mission in Bangkok benefited from the siege as piles of secret document were delivered to them directly from the Myanmar Embassy. How this was arranged is a mystery. The biggest loser was the God’s Army, led by two young Karen brothers, Johnny and Luther Htoo. God’s Army was exploited and tricked by the VBSW, who promised them new uniforms, food, medicine, weapons and ammunition in return for their support. None of their promises materialized. Kyaw Ni, aka “Big Johnny”, led the VBSW gunmen in the assault on the Myanmar Embassy. He was able to establish a close friendship with Johnny Htoo by supplying him with the cigarettes. Johnny Htoo is a chain smoker despite his young age. In a letter dated October 12, 1999, addressed to the Thai Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai, the VBSW apologized for their action and explained the motives behind the embassy takeover. |

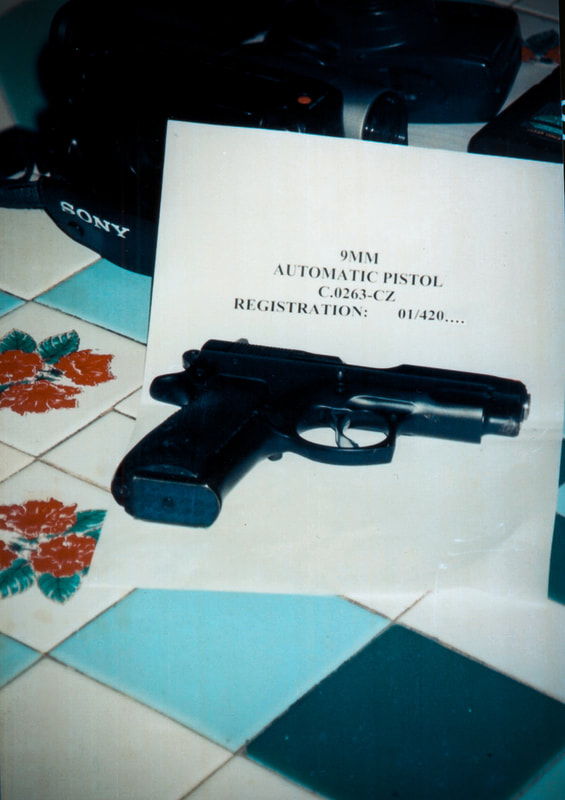

In a sign of reconciliation with the Thai government, the VBSW returned a pistol seized from the Special Branch policeman inside the embassy.

The handing of the pistol to the Thai official was done on behalf of the VBSW by the God’s Army military commander Shwe Bya at Takolan. This gesture by the VBSW encouraged the Thai government to dispatch a team of Thai negotiators on November 4, 1999, to meet with representatives of the VBSW and persuade them to surrender.

The Thai officials met with Kyaw Ni and Pida urging both to give up. Several VBSW members who arrived from the Maneeloy camp appealed to their comrades to give up and negotiate the terms of the surrender. Kyaw Ni and Pida refused and demanded to negotiate directly with the Thai PM. The Thai officials couldn’t accept this condition.

Making the situation worse, the unarmed Thai negotiators were humiliated during the surrender talks by about 30 God’s Army soldiers who encircled them inside Thai territory brandishing loaded weapons.

After the talks broke down the Thais didn’t retaliate against the God’s Army, although they clearly had the capability to do so. The VBSW gunmen and God’s Army soldiers were allowed to walk back several kilometers to their camp inside Myanmar.

The handing of the pistol to the Thai official was done on behalf of the VBSW by the God’s Army military commander Shwe Bya at Takolan. This gesture by the VBSW encouraged the Thai government to dispatch a team of Thai negotiators on November 4, 1999, to meet with representatives of the VBSW and persuade them to surrender.

The Thai officials met with Kyaw Ni and Pida urging both to give up. Several VBSW members who arrived from the Maneeloy camp appealed to their comrades to give up and negotiate the terms of the surrender. Kyaw Ni and Pida refused and demanded to negotiate directly with the Thai PM. The Thai officials couldn’t accept this condition.

Making the situation worse, the unarmed Thai negotiators were humiliated during the surrender talks by about 30 God’s Army soldiers who encircled them inside Thai territory brandishing loaded weapons.

After the talks broke down the Thais didn’t retaliate against the God’s Army, although they clearly had the capability to do so. The VBSW gunmen and God’s Army soldiers were allowed to walk back several kilometers to their camp inside Myanmar.

Following the Ratchaburi hospital incident on January 24, 1999, the God’s Army soldiers became even more disillusioned with the VBSW and started to question the promises made by Kyaw Ni of a better life and plenty of material goods. In fact, the living conditions of the God’s Army had deteriorated since then.

Johnny Htoo and Luther finally realized their association with the VBSW was leading them to disaster and withdrew their support. Johnny Htoo, who was previously always in the company of Kyaw Ni, abandoned him.

This move initiated a split within God’s Army, and ten of their soldiers, including Shwe Bya, formed the Democratic God’s Army (DGA) in March. The DGA retained strong ties with the VBSW.

Kyaw Ni planned to strike against Thai government facilities at any cost to avenge the death of his close friend Pida, two other Warriors and seven God’s Army soldiers killed at Ratchaburi hospital killed by a Thai security force. He reportedly targeted an oil refinery somewhere in Thailand. Fortunately, the DGA didn’t possess the capability to strike inside Thailand.

Kyaw Ni decided to kidnap four Thai workers employed by a Thai mining company contracted by the SPDC inside Myanmar in May. The DGA demanded a cool five million baht ransom from the company, but settled for two million baht. After they were paid the hostages were released unharmed. This incident was never reported even though Thai authorities knew about the kidnapping.

Starting on October 1, 1999, the KNU made a strong effort to convince their Karen brothers in God’s Army that they had chosen the wrong path in the struggle to free the Karen people from the SPDC terror by joining with the VBSW. Unfortunately, God’s Army started listening to the KNU only after a lot of damage had been done.

God’s Army managed to make headlines from several degrading interviews which didn’t help their cause. They were presented to the public as a kind of fanatical religious group.

As for the DGA, they are facing a grim future. Without any support they will vanish sooner or later. The group is suffering from shortages of food, medicine and ammunition and Kyaw Ni himself suffers from a serious skin disease. Obviously, the ransom money didn’t benefit them. There were some questions concerning his mental state while he lived at the Maneeloy camp.

The events which started on October 1, 1999 prove that the Myanmar opposition must employ political leadership and not just the barrel of a gun in order to achieve their objectives. There is no place for extremists.

Johnny Htoo and Luther finally realized their association with the VBSW was leading them to disaster and withdrew their support. Johnny Htoo, who was previously always in the company of Kyaw Ni, abandoned him.

This move initiated a split within God’s Army, and ten of their soldiers, including Shwe Bya, formed the Democratic God’s Army (DGA) in March. The DGA retained strong ties with the VBSW.

Kyaw Ni planned to strike against Thai government facilities at any cost to avenge the death of his close friend Pida, two other Warriors and seven God’s Army soldiers killed at Ratchaburi hospital killed by a Thai security force. He reportedly targeted an oil refinery somewhere in Thailand. Fortunately, the DGA didn’t possess the capability to strike inside Thailand.

Kyaw Ni decided to kidnap four Thai workers employed by a Thai mining company contracted by the SPDC inside Myanmar in May. The DGA demanded a cool five million baht ransom from the company, but settled for two million baht. After they were paid the hostages were released unharmed. This incident was never reported even though Thai authorities knew about the kidnapping.

Starting on October 1, 1999, the KNU made a strong effort to convince their Karen brothers in God’s Army that they had chosen the wrong path in the struggle to free the Karen people from the SPDC terror by joining with the VBSW. Unfortunately, God’s Army started listening to the KNU only after a lot of damage had been done.

God’s Army managed to make headlines from several degrading interviews which didn’t help their cause. They were presented to the public as a kind of fanatical religious group.

As for the DGA, they are facing a grim future. Without any support they will vanish sooner or later. The group is suffering from shortages of food, medicine and ammunition and Kyaw Ni himself suffers from a serious skin disease. Obviously, the ransom money didn’t benefit them. There were some questions concerning his mental state while he lived at the Maneeloy camp.

The events which started on October 1, 1999 prove that the Myanmar opposition must employ political leadership and not just the barrel of a gun in order to achieve their objectives. There is no place for extremists.

Behind the story:

It will be soon 20 years since the siege of the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok. Looking at all available information – which admittedly is sparse – it seems apparent that one Western intelligence service played a major role. The objective of the embassy operation was to acquire documents, and with the help of the VBSW, together with various exiles and God’s Army, who really didn’t know what was going on, this was achieved.

Some media sources reported that Westerners were seen in the vicinity of the embassy and actually gave a signal to the VBSW to enter the compound. The ambassador allegedly left the embassy before the seizure. Documents kept in an office vault were taken away by the intruders. How they managed to open the safe remains a mystery.

Hours before the embassy takeover God’s Army, led by their commander Shwe Bya, cleared an area, just across the Thai-Myanmar border for a helicopter to land. Because of my good relations with the God’s Army twin brothers and their friends in the KNU, I was asked by certain Thai authorities to recover the pistol seized by the VBSW from the Special Branch policeman at the embassy. I made the arrangements, with logistical support from the Thai authorities. A highly respected KNU man, Saw Thaw Thi, negotiated with Shwe Bya for return of the Czechmade CZ pistol and guaranteed my safety.

On October 24, 1999, I walked into a shack in Takolan where Saw Thaw Thi (KNU member, my friend and guide) and Shwe Bya together with other God’s Army soldiers were present. Saw Thaw Thi checked the registration number of the gun. It matched. Shwe Bya handed me the pistol on behalf of the VBSW plus a sealed letter from them addressed to Prime Minister Chuan. Thai officials who waited for me in the distance collected both items. The operation went smoothly, without a hitch.

That success prompted Thai officials to ask me to persuade Kyaw Ni and Pida to surrender and come out the jungle where they were staying with God’s Army child soldiers. This was of course before the ill-fated raid on Ratchaburi hospital where Pida and some God’s Army soldiers were killed.

The Thais wanted God’s Army to stop fighting and live peacefully. Separating them from the VBSW, who allegedly were supported by one Western intelligence service, was an important step. Kyaw Ni and Pida had gained influence over the God’s Army twins by supplying cigarettes and playing with them. It was that simple. The message I was to give to Kyaw Ni and Pida was that after they gave up they would be treated well, housed in a guesthouse instead of being sent to prison and allowed to negotiate (whatever this meant) with the Thai authorities.

On November 4 police cars patrolled many roads around Suan Phung and other Thai forces swarmed the area, later joined by a contingent of media who arrived from Bangkok. Helicopters were flying above.

I walked in the jungle following armed soldiers and BPP who were watching for mines. The group included Thai officials and several Warriors from the Maneeloy camp. After we reached a Thai Army base we walked for a while after God’s Army soldiers appeared suddenly from the darkness in a roughly predetermined location on Thai territory at around 6.30pm.

I was greeted by the twins and other members of the God’s Army. Kyaw Ni and Pida emerged from the bushes later on both brandishing AK-47 assault rifles. I relayed the terms of surrender to them. Kyaw Ni appeared agitated while Pida was calm. The two defectors who apparently set up the meeting then spoke with them. Thai negotiators protected by two bodyguards, one armed with an HK machinegun with silencer, spoke to the Kyaw Ni and Pida as well.

Kyaw Ni refused to surrender and called on the twins to decide his fate. It was learned later that the God’s Army interpreter tricked the twins into saying they wanted him to stay.

After Kyaw Ni listened again to my pleas asking him to give up, he got even more agitated and pointed his AK-47 at me. Three Warriors and other people rushed to us and tried to calm him down. Kyaw Ni then disappeared into the darkness followed by Pida and the God’s Army contingent. The operation was a failure.

We returned tired and disappointed to the Army base in Suan Phung, where reporters waited outside the gate. If Kyaw Ni and Pida had surrendered then the Ratchaburi hospital incident would never have taken place.

Later on, a VBSW member disclosed that Kyaw Ni and Pida had originally intended to surrender that night. He claimed that a Western intelligence agency had learned of their intentions and warned them that if they surrender they would be jailed in Thailand or transferred to Myanmar to face execution. “Someone was afraid that they might reveal secrets to Thai investigators or the media,” said the source. The VBSW were equipped with an expensive satellite

It will be soon 20 years since the siege of the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok. Looking at all available information – which admittedly is sparse – it seems apparent that one Western intelligence service played a major role. The objective of the embassy operation was to acquire documents, and with the help of the VBSW, together with various exiles and God’s Army, who really didn’t know what was going on, this was achieved.

Some media sources reported that Westerners were seen in the vicinity of the embassy and actually gave a signal to the VBSW to enter the compound. The ambassador allegedly left the embassy before the seizure. Documents kept in an office vault were taken away by the intruders. How they managed to open the safe remains a mystery.

Hours before the embassy takeover God’s Army, led by their commander Shwe Bya, cleared an area, just across the Thai-Myanmar border for a helicopter to land. Because of my good relations with the God’s Army twin brothers and their friends in the KNU, I was asked by certain Thai authorities to recover the pistol seized by the VBSW from the Special Branch policeman at the embassy. I made the arrangements, with logistical support from the Thai authorities. A highly respected KNU man, Saw Thaw Thi, negotiated with Shwe Bya for return of the Czechmade CZ pistol and guaranteed my safety.

On October 24, 1999, I walked into a shack in Takolan where Saw Thaw Thi (KNU member, my friend and guide) and Shwe Bya together with other God’s Army soldiers were present. Saw Thaw Thi checked the registration number of the gun. It matched. Shwe Bya handed me the pistol on behalf of the VBSW plus a sealed letter from them addressed to Prime Minister Chuan. Thai officials who waited for me in the distance collected both items. The operation went smoothly, without a hitch.

That success prompted Thai officials to ask me to persuade Kyaw Ni and Pida to surrender and come out the jungle where they were staying with God’s Army child soldiers. This was of course before the ill-fated raid on Ratchaburi hospital where Pida and some God’s Army soldiers were killed.

The Thais wanted God’s Army to stop fighting and live peacefully. Separating them from the VBSW, who allegedly were supported by one Western intelligence service, was an important step. Kyaw Ni and Pida had gained influence over the God’s Army twins by supplying cigarettes and playing with them. It was that simple. The message I was to give to Kyaw Ni and Pida was that after they gave up they would be treated well, housed in a guesthouse instead of being sent to prison and allowed to negotiate (whatever this meant) with the Thai authorities.

On November 4 police cars patrolled many roads around Suan Phung and other Thai forces swarmed the area, later joined by a contingent of media who arrived from Bangkok. Helicopters were flying above.

I walked in the jungle following armed soldiers and BPP who were watching for mines. The group included Thai officials and several Warriors from the Maneeloy camp. After we reached a Thai Army base we walked for a while after God’s Army soldiers appeared suddenly from the darkness in a roughly predetermined location on Thai territory at around 6.30pm.

I was greeted by the twins and other members of the God’s Army. Kyaw Ni and Pida emerged from the bushes later on both brandishing AK-47 assault rifles. I relayed the terms of surrender to them. Kyaw Ni appeared agitated while Pida was calm. The two defectors who apparently set up the meeting then spoke with them. Thai negotiators protected by two bodyguards, one armed with an HK machinegun with silencer, spoke to the Kyaw Ni and Pida as well.

Kyaw Ni refused to surrender and called on the twins to decide his fate. It was learned later that the God’s Army interpreter tricked the twins into saying they wanted him to stay.

After Kyaw Ni listened again to my pleas asking him to give up, he got even more agitated and pointed his AK-47 at me. Three Warriors and other people rushed to us and tried to calm him down. Kyaw Ni then disappeared into the darkness followed by Pida and the God’s Army contingent. The operation was a failure.

We returned tired and disappointed to the Army base in Suan Phung, where reporters waited outside the gate. If Kyaw Ni and Pida had surrendered then the Ratchaburi hospital incident would never have taken place.

Later on, a VBSW member disclosed that Kyaw Ni and Pida had originally intended to surrender that night. He claimed that a Western intelligence agency had learned of their intentions and warned them that if they surrender they would be jailed in Thailand or transferred to Myanmar to face execution. “Someone was afraid that they might reveal secrets to Thai investigators or the media,” said the source. The VBSW were equipped with an expensive satellite

RSS Feed

RSS Feed