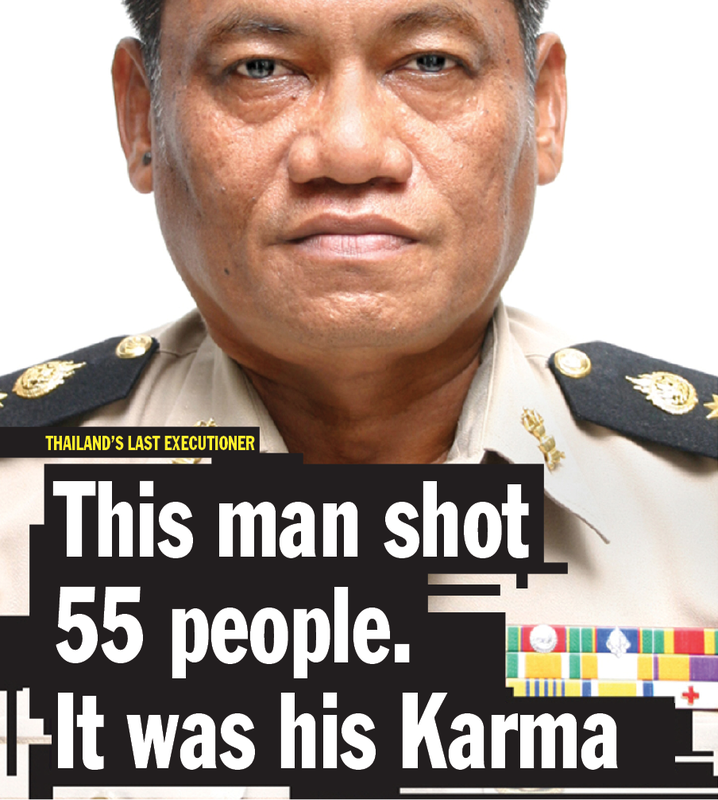

This man shot 55 people. It was his Karma

A new movie being released this month tells the chilling story of Chavoret Jaruboon, who executed 55 people in a 19-year career at Bang Kwang Prison. DON LINDER, who wrote the screenplay, met Chavoret and remembers in this article a man of many surprisingly good qualities

A new movie being released this month tells the chilling story of Chavoret Jaruboon, who executed 55 people in a 19-year career at Bang Kwang Prison. DON LINDER, who wrote the screenplay, met Chavoret and remembers in this article a man of many surprisingly good qualities

| KHUN Chavoret Jaruboon executed 55 people, including one woman. And yet, I am very sorry we never got to be closer friends. Khun Chavoret is better known as “The Last Executioner,” which is also the title of his 2006 autobiography in English. He worked at Bang Kwang Prison (sensationalized as ‘The Bangkok Hilton’ in the movie with Nicole Kidman) for 33 years, and was the executioner from 1984 to 2003. So, 55 executions over 19 years – it wasn’t exactly like he arrived at work each day, punched the clock, and killed someone, although it certainly was an odd career. Chavoret is known as the last executioner because he was the last person in Thailand whose job it was to carry out court-ordered executions by gun before the switchover to lethal injection, which is the method still used. |

| I wrote the screenplay of his life story – a story of life at its most beautiful and death at its most surreal – which will be released nationwide this month, produced by DeWarrenne Pictures. The experience of writing the film has been almost as bizarre as the story itself. I first met Chavoret in April 2007 at the FCCT (Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand), when he was part of a panel discussion on prison life. The others on the panel were Susan Aldous, known as ‘The Angel of Bangkok’ for her work with slum children and prisoners at Bang Kwang, and the Thai owner of a travel agency arrested for money laundering. During the evening, my overwhelming impression of Chavoret was that he was so normal. Watching him sitting there in a polo shirt and Dockers – no black hood and scythe – he looked like anyone I might sit next to on the BTS or in Starbucks. When it came to the Q and A, the questions were unusually softball for the FCCT crowd. I ended up asking the last questions, which went something like this: “You seem like a nice guy and all, but how did you reconcile your work with your Buddhism? What did you tell your family? Did you go out for beers with the guys after executions?” (It turns out he did). |

I now know that Chavoret had answered variants of these questions a thousand times before. His answers focused on karma. It was his karma to do this job, and he was compassionately helping the prisoners to achieve their karma. It was his duty, after all. At the time, this all smacked of a well devised construction of denial, or worse, an “I was just following orders” defense. I wanted to know more, so I introduced myself and asked for an interview, which his editor arranged.

A week later, I was in Chavoret’s office at Bang Kwang’s Foreign Affairs Division which he now headed. Of course, I’d read the book by then, so I knew of his background. Nevertheless, it was still very weird when, without any explanation, this 59-year-old executioner sat across his desk from me and for 30 minutes played air guitar and sang Beatles, Elvis, and Ventures songs. Then, we talked. And talked…for almost five hours.

It turns out that in his late teens and early 20s, he was a wild rock and roller, who played guitar behind his back while his drummer hung from the ceiling, and sometimes smashed his guitars. He was really cool, dressed in the tightest 60s pants and skinny ties. He and his band, Mitra, played the bars in Udon, Ubon, and Bangkok where the American GIs partied on R&R from the Vietnam War. His favorite bar was aptly named (for an executioner-to-be) “Sorry About That” in Udon.

During this time, he met his sweetheart, Khun Tew, whom he married and stayed with for 43 years until his death last year. When Khun Tew announced she was pregnant, Chavoret, whose father was a teacher, decided he needed to do the “respectable” thing and get a practical job so he could support a family.

After leaving his first love (rock and roll) behind for his next love, he tried a succession of jobs – teacher, translator on an oil rig, paramedic – but none felt right. Then, a cousin told him of a civil service exam for prison guards.

Chavoret liked the guaranteed work, pension, and education benefits for his kids, so he took the exam. He didn’t plan to be an executioner. It just happened. It was his karma.

Throughout history, executions in Thailand have always been very choreographed, and often very cruel. If you go to the Correction Museum on Mahachai Road in Bangkok, you can see paintings and dioramas of Thai torture and execution methods from the Ayutthaya Period (1350-1767) to the present.

Among the 50 or so Ayutthaya Period tortures illustrated, my favourite (a strange word in this context) is when they cut off the flesh of a live prisoner, grilled it, and force fed it to him. Beheadings were the legal execution method from 1903-1934, and these were pretty grisly events involving a second person whose job it was to dance in front of the prisoner and try to distract him while his head was hacked off and then placed on a stick for all to see.

Up through the 1930s there was even a practice of locking the prisoner into a giant hackeysack ball with spikes inside and getting an elephant to roll it around.

From 1934-2003, executions were done by gun, until the switch to lethal injection.

During Chavoret’s tenure at Bang Kwang, the process was – and still is – the epitome of division of labor. Chavoret started at the lowest job, and because he was such a responsible and precision-oriented worker, he rose through the ranks to when he was offered the executioner’s job. It’s worth going through all the jobs to know the context in which he worked.

A week later, I was in Chavoret’s office at Bang Kwang’s Foreign Affairs Division which he now headed. Of course, I’d read the book by then, so I knew of his background. Nevertheless, it was still very weird when, without any explanation, this 59-year-old executioner sat across his desk from me and for 30 minutes played air guitar and sang Beatles, Elvis, and Ventures songs. Then, we talked. And talked…for almost five hours.

It turns out that in his late teens and early 20s, he was a wild rock and roller, who played guitar behind his back while his drummer hung from the ceiling, and sometimes smashed his guitars. He was really cool, dressed in the tightest 60s pants and skinny ties. He and his band, Mitra, played the bars in Udon, Ubon, and Bangkok where the American GIs partied on R&R from the Vietnam War. His favorite bar was aptly named (for an executioner-to-be) “Sorry About That” in Udon.

During this time, he met his sweetheart, Khun Tew, whom he married and stayed with for 43 years until his death last year. When Khun Tew announced she was pregnant, Chavoret, whose father was a teacher, decided he needed to do the “respectable” thing and get a practical job so he could support a family.

After leaving his first love (rock and roll) behind for his next love, he tried a succession of jobs – teacher, translator on an oil rig, paramedic – but none felt right. Then, a cousin told him of a civil service exam for prison guards.

Chavoret liked the guaranteed work, pension, and education benefits for his kids, so he took the exam. He didn’t plan to be an executioner. It just happened. It was his karma.

Throughout history, executions in Thailand have always been very choreographed, and often very cruel. If you go to the Correction Museum on Mahachai Road in Bangkok, you can see paintings and dioramas of Thai torture and execution methods from the Ayutthaya Period (1350-1767) to the present.

Among the 50 or so Ayutthaya Period tortures illustrated, my favourite (a strange word in this context) is when they cut off the flesh of a live prisoner, grilled it, and force fed it to him. Beheadings were the legal execution method from 1903-1934, and these were pretty grisly events involving a second person whose job it was to dance in front of the prisoner and try to distract him while his head was hacked off and then placed on a stick for all to see.

Up through the 1930s there was even a practice of locking the prisoner into a giant hackeysack ball with spikes inside and getting an elephant to roll it around.

From 1934-2003, executions were done by gun, until the switch to lethal injection.

During Chavoret’s tenure at Bang Kwang, the process was – and still is – the epitome of division of labor. Chavoret started at the lowest job, and because he was such a responsible and precision-oriented worker, he rose through the ranks to when he was offered the executioner’s job. It’s worth going through all the jobs to know the context in which he worked.

First is the pi liang, whose job it is to get the prisoner from death row. Prisoners on death row are still shackled by foot 23 hours a day. There was no advanced notice about executions, so when a pi liang came, they all knew someone would be dead within a few hours. Next, an escort walked the prisoner, still in shackles, across the prison yard, which was full of prison personnel, doctors, government officials, and witnesses.

Next stop was the octagonal “cool pavilion,” where the prisoner met with a monk and was photographed and fingerprinted for identification. A guard was assigned to give the prisoner a pencil and paper to write anything he wanted – a letter to his family, to the King, or to Lord Buddha, or his last will and testament. The next job was to blindfold the prisoner, give him a lotus and some joss sticks, and walk him into the execution room under a sign which read ‘The End of All Suffering.’ (Chavoret later in life said it more correctly should have read ‘Death Chamber’).

The next job was to tie the prisoner to a standing wooden cross, so he would be facing a wall of sand bags with his back to the executioner. The prisoner was tied to this crucifix with his hands holding the lotus in front of him. The next guard positioned a standing wooden frame with a cloth screen between the prisoner and the executioner, and attached a small cardboard bulls eye target on the screen corresponding to where the prisoner’s heart would be if shot from behind.

Another would wheel in the gun, check the mechanism, load the cartridges, and aim it. Finally, the executioner would enter, wai, and ask forgiveness of the soon-to-be-executed and Mother Earth (because blood would spill on the earth), and at the drop of a red flag, he would pull the trigger.

The gun used was a machine gun. Yes. A machine gun! Chavoret told me they loaded 15 rounds, and he typically got off 9-12 rounds in bursts of three. So, the prisoner was pretty well sliced-and-diced at the end of this long dance.

About two years ago, I met Tom Waller, the film’s producer/director and owner of DeWarrenne Pictures, at a mutual friend’s birthday dinner. I don’t remember how or why the conversation got around to executions, but it turned out that Tom had for some time wanted to do a film of the story, and I had hours of personal interaction with Chavoret, so it was a good match.

To me the core of the story has always been the archetypal struggle of the artist against his or her need for a practical self. As I wrote the film that core belief remained, fleshed out by the incredible access I’ve had to Chavoret’s family, childhood friends, monk confidante, former band mates, and prison colleagues.

I’ve had access to his artifacts – amulets, shrines, mobile phone. I’ve even held a few of the used targets, complete with bullet holes and Chavoret’s handwritten notes on the back. Mostly, I’ve gained insight into how strongly karma and the spirit world are very real dimensions of daily Thai life, including Chavoret’s.

From my meetings with him and those around him, it is clear that Chavoret was a gentle, funny, caring, and very family oriented man. Khun Tew was truly the love of his life, and he would sacrifice anything in order to provide a better life for his daughter and two sons, and the granddaughter he loved so much. His family, whom I’ve met many times, are among the nicest and most well-adjusted people I have ever known.

Next stop was the octagonal “cool pavilion,” where the prisoner met with a monk and was photographed and fingerprinted for identification. A guard was assigned to give the prisoner a pencil and paper to write anything he wanted – a letter to his family, to the King, or to Lord Buddha, or his last will and testament. The next job was to blindfold the prisoner, give him a lotus and some joss sticks, and walk him into the execution room under a sign which read ‘The End of All Suffering.’ (Chavoret later in life said it more correctly should have read ‘Death Chamber’).

The next job was to tie the prisoner to a standing wooden cross, so he would be facing a wall of sand bags with his back to the executioner. The prisoner was tied to this crucifix with his hands holding the lotus in front of him. The next guard positioned a standing wooden frame with a cloth screen between the prisoner and the executioner, and attached a small cardboard bulls eye target on the screen corresponding to where the prisoner’s heart would be if shot from behind.

Another would wheel in the gun, check the mechanism, load the cartridges, and aim it. Finally, the executioner would enter, wai, and ask forgiveness of the soon-to-be-executed and Mother Earth (because blood would spill on the earth), and at the drop of a red flag, he would pull the trigger.

The gun used was a machine gun. Yes. A machine gun! Chavoret told me they loaded 15 rounds, and he typically got off 9-12 rounds in bursts of three. So, the prisoner was pretty well sliced-and-diced at the end of this long dance.

About two years ago, I met Tom Waller, the film’s producer/director and owner of DeWarrenne Pictures, at a mutual friend’s birthday dinner. I don’t remember how or why the conversation got around to executions, but it turned out that Tom had for some time wanted to do a film of the story, and I had hours of personal interaction with Chavoret, so it was a good match.

To me the core of the story has always been the archetypal struggle of the artist against his or her need for a practical self. As I wrote the film that core belief remained, fleshed out by the incredible access I’ve had to Chavoret’s family, childhood friends, monk confidante, former band mates, and prison colleagues.

I’ve had access to his artifacts – amulets, shrines, mobile phone. I’ve even held a few of the used targets, complete with bullet holes and Chavoret’s handwritten notes on the back. Mostly, I’ve gained insight into how strongly karma and the spirit world are very real dimensions of daily Thai life, including Chavoret’s.

From my meetings with him and those around him, it is clear that Chavoret was a gentle, funny, caring, and very family oriented man. Khun Tew was truly the love of his life, and he would sacrifice anything in order to provide a better life for his daughter and two sons, and the granddaughter he loved so much. His family, whom I’ve met many times, are among the nicest and most well-adjusted people I have ever known.

| Chavoret was also a very calm guy. His typical pose, in any type of situation be it at his desk, on a television interview, or lecturing a group of students, was with his hands clasped in front of his belly – that is, when he wasn’t knocking out some rock and roll riffs. He loved to eat, especially German food – his favourite was pigs’ knuckle – and he loved to drink, but he was by no means a drunk. He played guitar throughout his life, and he loved karaoke, but was terrible at singing Thai songs. His favourite karaoke song was Sinatra’s ‘My Way.’ He also loved American folk music, and American country and western (he sang a lot of Hank Williams). If he had ever gone to a shrink, he would have been diagnosed with OCD – he was extremely detailed and ordered (before an execution, he would come home, take a bath, nap, and put on a clean, freshly pressed uniform). I’ve discussed the moral and ethical dimensions of his work with him and those around him, including Phra Ajarn Boonnam, his confidante. Basically, it boils down to karma and duty. When specifically asked if he feared he’d built up bad karma, he explained to me that karma depends on intent, and Chavoret had no murderous intent. “He was an executioner, not a killer,” he told me. Chavoret also had an incredible sense of duty, primarily to his family, but also to his superiors. When I asked if he could have refused the offer to become executioner, he said “absolutely not.” Besides, he received an extra 2,000 baht for each execution, and that money could help his family. |

There is a kind of karmic irony to the story. When Chavoret retired about four years ago, he and Tew envisioned an easy life ahead. Shortly after, he developed cancer – first of the intestine and then of the brain – and much of his last years were very painful. He never gave up, though. Together, he and Phra Boonnam lectured on the dangers of drugs and criminal life, Chavoret appeared on endless television interviews, including a bizarre appearance on a game show modeled after the American show ‘To Tell the Truth,’ and he wrote two books in English and four in Thai.

The final dimension of this story is the spirit world, which as a Westerner, I’ve come to realize is as real to some Thais as the silverware. Although Chavoret was not a religious man (he considered himself very spiritual), he did take measures to protect himself from the spirits of the executed and from Yama, the Spirit of Death, who plagued him his whole life.

I understood that in order to write the story, I had to practice a lot of willing suspension of disbelief and make karma and spirits a natural and seamless part of the narrative. Maybe it isn’t such a stretch considering that Chavoret told me a story of his 15th birthday when his father gave him his first guitar and took him to a monk fortune teller. “Your fate is to work with death,” he was told.

In the film, the actor Vithaya Pansringarm, who recently appeared in ‘Only God Forgives’ and in the DeWarrenne Pictures’ ‘Mindfulness and Murder,’ delivers an incredible performance in which he virtually transforms himself into Chavoret Jaruboon.

David Asavanond gives a stunning performance as The Spirit, moving seamlessly through various manifestations of Death, always keeping it real even in the most surreal situations. And, look for Duangjai Hirunsri’s performance as the only woman Chavoret executed, ironically also named Duangjai.

The last thing I remember Chavoret telling me is, “We Thais believe in destiny and fate. I believe in karma.”

Chavoret Jaruboon died on 30 April 2012 at the age of 64.

The final dimension of this story is the spirit world, which as a Westerner, I’ve come to realize is as real to some Thais as the silverware. Although Chavoret was not a religious man (he considered himself very spiritual), he did take measures to protect himself from the spirits of the executed and from Yama, the Spirit of Death, who plagued him his whole life.

I understood that in order to write the story, I had to practice a lot of willing suspension of disbelief and make karma and spirits a natural and seamless part of the narrative. Maybe it isn’t such a stretch considering that Chavoret told me a story of his 15th birthday when his father gave him his first guitar and took him to a monk fortune teller. “Your fate is to work with death,” he was told.

In the film, the actor Vithaya Pansringarm, who recently appeared in ‘Only God Forgives’ and in the DeWarrenne Pictures’ ‘Mindfulness and Murder,’ delivers an incredible performance in which he virtually transforms himself into Chavoret Jaruboon.

David Asavanond gives a stunning performance as The Spirit, moving seamlessly through various manifestations of Death, always keeping it real even in the most surreal situations. And, look for Duangjai Hirunsri’s performance as the only woman Chavoret executed, ironically also named Duangjai.

The last thing I remember Chavoret telling me is, “We Thais believe in destiny and fate. I believe in karma.”

Chavoret Jaruboon died on 30 April 2012 at the age of 64.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed