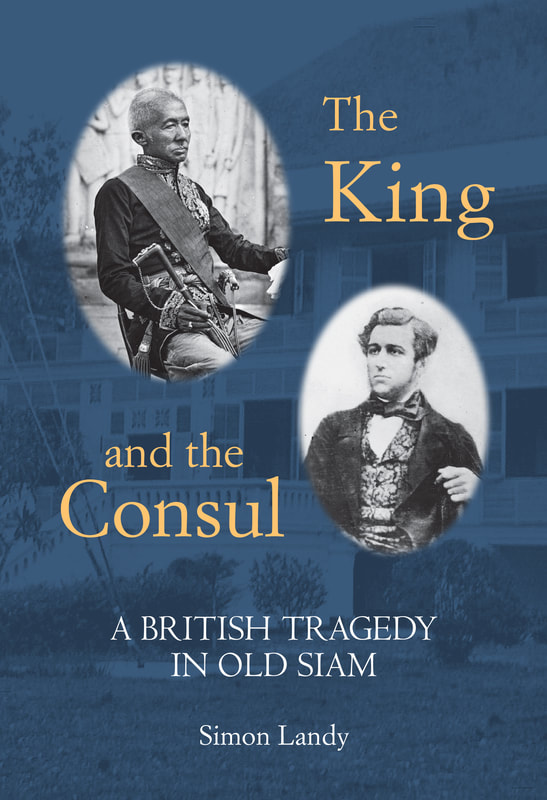

| Inspired by the much-debated sale of the British Embassy compound in Bangkok in 2018, former property executive Simon Landy set about researching the history of foreign land ownership in Thailand dating back to the reign of King Mongkut in the 19th century. His work has resulted in a fascinating book ‘The King and the Consul,’ which the author has subtitled ‘A British tragedy in old Siam’ to highlight the untimely death of the first British senior diplomat in the country while negotiating a suitable site for Britain’s consulate using a nominee structure familiar to today’s foreign buyers to get round ownership laws. |

| What inspired you to write The King and the Consul? The idea came from the sale of the British Embassy Bangkok compound on the corner of Ploenchit and Wireless Roads. There were rumours that the land had been granted to the British government by the Thai authorities, and so shouldn’t (or couldn’t!) be sold for profit. That rumour, I discovered, wasn’t true. But in looking into it, I came across the amazing story of how the British were granted their first compound on the river in 1856. And that’s the core story in my book. Is this your first book? It’s the first book, yes, although I’ve been writing articles and papers for decades. Before the book came out, I had two papers published on related topics – one in the Journal of the Siam Society, the other in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong. Please tell us about your background and life in Thailand. In a nutshell, I first moved to Thailand in 1981 to teach at Chulalongkorn University. The job was great, the pay not so much. When I got married and became a father I moved into the business world, eventually focusing on the property consulting business. My last job was as executive chairman of Colliers International Thailand and I retired from that in 2017. Please explain how Thailand’s current view of foreign land ownership was largely shaped by a treaty with Britain dating back almost 150 years ago, and the involvement of several key characters featured in your book. |

The Bowring treaty of 1855 was mainly about giving Brits trading rights in Siam, as Thailand was called then. King Mongkut and his senior officials were also worried that British traders would flood in and buy up prime land, so the treaty restricted them to renting near the city centre. Just a year after the treaty, one British trader, a Captain Puddicombe, tried to ‘game’ the rules by using a nominee structure. The lease agreement was signed off at the British consulate under the first consul, Charles Hillier. Hillier had only opened the consulate a couple of months before this happened.

When the Siamese authorities found out about it, they were furious, which led to the tragedy of the book’s subtitle. The market today is much more sophisticated, but we still find some foreigners trying to use nominee structures to circumvent the ownership laws, which are among the most illiberal in the region.

What was King Mongkut’s role in ‘modernising’ Siam and was the country regarded by competing British and French colonial interests as a convenient buffer to keep them apart?

Of course, what looks restrictive today may have seemed the opposite 150 years ago. King Mongkut was actually a great reformer. As soon as he became king, he started to open up the country to foreign trade. Unlike a lot of his advisors and neighbours he understood that the British interest in the region was essentially to develop trade, not to seize territory. That realisation enabled him and his son, King Chulalongkorn, to maintain the country’s independence while all the neighbours (Burma, Malaya, Cambodia, Vietnam) became colonies.

Because of this, I think that the popular idea that the British and French maintained Siam as a convenient buffer between their empires is only true in part.

When the Siamese authorities found out about it, they were furious, which led to the tragedy of the book’s subtitle. The market today is much more sophisticated, but we still find some foreigners trying to use nominee structures to circumvent the ownership laws, which are among the most illiberal in the region.

What was King Mongkut’s role in ‘modernising’ Siam and was the country regarded by competing British and French colonial interests as a convenient buffer to keep them apart?

Of course, what looks restrictive today may have seemed the opposite 150 years ago. King Mongkut was actually a great reformer. As soon as he became king, he started to open up the country to foreign trade. Unlike a lot of his advisors and neighbours he understood that the British interest in the region was essentially to develop trade, not to seize territory. That realisation enabled him and his son, King Chulalongkorn, to maintain the country’s independence while all the neighbours (Burma, Malaya, Cambodia, Vietnam) became colonies.

Because of this, I think that the popular idea that the British and French maintained Siam as a convenient buffer between their empires is only true in part.

"King Mongkut understood that the British interest in the region was essentially to develop trade, not to seize territory. That realisation enabled him and his son, King Chulalongkorn, to maintain the country's independence while all the neighboring countries became colonies "

Who or what were your major sources of background / historical information?

I relied mainly on primary sources. There’s a huge amount of partially explored material in the UK and Thai archives: dispatches from and to the British consulate in Bangkok to Bowing in Hong Kong and the Foreign Secretary in London; internal correspondence in the China and London Office archives; proclamations and correspondence of King Mongkut and various of his officials in Siam etc.

I also dipped into the French and US archives on the period. Apart from a handful of excellent books, the most interesting secondary sources I found were some unpublished doctoral theses. Then of course, I was lucky enough to meet and discuss the topic with a few really brilliant people – historians and others – in Thailand and elsewhere.

Did you have Thai researchers to help you?

I had some help from a Thai history student in the Thai archives when I came across language that was unfamiliar to me, but overall I found the language and writing of the period more modern than I’d expected.

How long did it take you to complete the book?

I’d say from start to finish about 20 months. That doesn’t include a long delay for Covid. I’d almost finished the book when Covid hit, but had to put the final touches and publishing on hold until I could get back into the libraries to recheck references.

Will the book be translated into Thai?

There’s no immediate plans for a Thai version, although I’ve had a number of people ask. It’s not something I could do on my own, so I’m not sure who would be willing and able to take on a challenge like that!

Do you think Thailand’s laws regarding foreign ownership of land are fair and reasonable, or overly restrictive? Should they be changed, especially in view of the current desire for greater inward investment to help offset the country’s Covid-affected economy?

I do think the laws are overly restrictive, although I also understand the government’s difficulties in changing the status quo. As we’ve again seen recently, ministers often announce plans to liberalise the law – usually either allowing a higher foreign ownership percentage in condominiums, increasing the maximum lease length or permitting foreign ownership in specific sectors – but these plans almost always get rejected by the bureaucracy or others before they can become laws.

I’m not sure if liberalising land ownership would help generate that much more inward investment, but it should help make the market less opaque and inequitable, particularly for commercial property. The residential property market is already very competitive, but the commercial property market is dominated by a handful of local entrepreneurs. More liberal laws would enable foreign investors to compete in the commercial market which would lead to more transparency and a fairer market overall.

For many British residents of Thailand, the sale and subsequent demolition of the British Embassy last year was another ‘tragedy’. Could it or should it have been avoided, and what did this episode say about Britain’s place in SE Asia?

The Bangkok embassy land was one of the most (if not the most) expensive asset on the FCO’s balance sheet. It stood out like a sore thumb, which made it difficult to defend in economic terms. If a sale couldn’t be avoided, they could have tried to preserve the historic assets – the 95-year-old residence, the war memorial and Queen Victoria’s statue. I argued that there was a way to keep those assets and still get a high price (almost the same price) for the rest of the land. But the FCO wasn’t interested. They wanted to make the sale as simple as possible – i.e. with no encumbrances. I think it was a poor decision and very damaging to Britain’s soft power in SE Asia.

Who actually owned the land occupied by the British Embassy on Ploenchit?

It was owned by the British government. They bought it from the Nai Lert family in the 1920s.

I relied mainly on primary sources. There’s a huge amount of partially explored material in the UK and Thai archives: dispatches from and to the British consulate in Bangkok to Bowing in Hong Kong and the Foreign Secretary in London; internal correspondence in the China and London Office archives; proclamations and correspondence of King Mongkut and various of his officials in Siam etc.

I also dipped into the French and US archives on the period. Apart from a handful of excellent books, the most interesting secondary sources I found were some unpublished doctoral theses. Then of course, I was lucky enough to meet and discuss the topic with a few really brilliant people – historians and others – in Thailand and elsewhere.

Did you have Thai researchers to help you?

I had some help from a Thai history student in the Thai archives when I came across language that was unfamiliar to me, but overall I found the language and writing of the period more modern than I’d expected.

How long did it take you to complete the book?

I’d say from start to finish about 20 months. That doesn’t include a long delay for Covid. I’d almost finished the book when Covid hit, but had to put the final touches and publishing on hold until I could get back into the libraries to recheck references.

Will the book be translated into Thai?

There’s no immediate plans for a Thai version, although I’ve had a number of people ask. It’s not something I could do on my own, so I’m not sure who would be willing and able to take on a challenge like that!

Do you think Thailand’s laws regarding foreign ownership of land are fair and reasonable, or overly restrictive? Should they be changed, especially in view of the current desire for greater inward investment to help offset the country’s Covid-affected economy?

I do think the laws are overly restrictive, although I also understand the government’s difficulties in changing the status quo. As we’ve again seen recently, ministers often announce plans to liberalise the law – usually either allowing a higher foreign ownership percentage in condominiums, increasing the maximum lease length or permitting foreign ownership in specific sectors – but these plans almost always get rejected by the bureaucracy or others before they can become laws.

I’m not sure if liberalising land ownership would help generate that much more inward investment, but it should help make the market less opaque and inequitable, particularly for commercial property. The residential property market is already very competitive, but the commercial property market is dominated by a handful of local entrepreneurs. More liberal laws would enable foreign investors to compete in the commercial market which would lead to more transparency and a fairer market overall.

For many British residents of Thailand, the sale and subsequent demolition of the British Embassy last year was another ‘tragedy’. Could it or should it have been avoided, and what did this episode say about Britain’s place in SE Asia?

The Bangkok embassy land was one of the most (if not the most) expensive asset on the FCO’s balance sheet. It stood out like a sore thumb, which made it difficult to defend in economic terms. If a sale couldn’t be avoided, they could have tried to preserve the historic assets – the 95-year-old residence, the war memorial and Queen Victoria’s statue. I argued that there was a way to keep those assets and still get a high price (almost the same price) for the rest of the land. But the FCO wasn’t interested. They wanted to make the sale as simple as possible – i.e. with no encumbrances. I think it was a poor decision and very damaging to Britain’s soft power in SE Asia.

Who actually owned the land occupied by the British Embassy on Ploenchit?

It was owned by the British government. They bought it from the Nai Lert family in the 1920s.

What has been the reaction to the book so far?

So far, so good, I’m pleased to say. Khunying Narisa of River Books, the publisher, tells me that sales have been good and comments and reviews that I’ve seen have all been positive. Of course, if people hate the book they may not be telling me that!

Are you planning any other books?

Lots of plans, but nothing firm yet. Watch this space!

Is Thailand willing to see greater revision of its history?

There are actually some really excellent Thai historians who are looking at Thai history from new perspectives and producing interesting books. The issue is really about what is taught in schools. If the curriculum is stuck in the past and continues to rely on a one-sided interpretation of history, it is difficult to see how Thailand can develop a deeper understanding of where it’s come from and where it’s going.

So far, so good, I’m pleased to say. Khunying Narisa of River Books, the publisher, tells me that sales have been good and comments and reviews that I’ve seen have all been positive. Of course, if people hate the book they may not be telling me that!

Are you planning any other books?

Lots of plans, but nothing firm yet. Watch this space!

Is Thailand willing to see greater revision of its history?

There are actually some really excellent Thai historians who are looking at Thai history from new perspectives and producing interesting books. The issue is really about what is taught in schools. If the curriculum is stuck in the past and continues to rely on a one-sided interpretation of history, it is difficult to see how Thailand can develop a deeper understanding of where it’s come from and where it’s going.

"If a sale of the Embassy couldn’t be avoided, the Foreign Office could have tried to preserve the historic assets – the 95-year-old residence, the war memorial and Queen Victoria’s statue. I argued that there was a way to keep those assets and still get a high price (almost the same price) for the rest of the land. But the FCO wasn’t interested. I think it was a poor decision and very damaging to Britain’s soft power in SE Asia."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed