On three occasions over a 20-year period beginning in 1960, Roy Howard headed THAI Airways International’s advertising department. Many remember these years as THAI’s golden era, when it reigned supreme amongst Asia’s airlines. Now retired and living once again in Bangkok after Australia and Hong Kong, Roy recalls his work at THAI, and the many people and events that shaped his life and the airline’s development

| A CHANCE interview brought me to Bangkok in 1959, and the launch of THAI the following year was the start of a 32-year association with the airline. It also gave me the opportunity to live and work in Thailand before it was overrun by tourists, and Bangkok was turned from a tranquil city of one-million friendly people, interlaced with lotus-filled klongs, into a concrete jungle of more than eight million hustling and bustling souls. When I disembarked at Bangkok airport in June, 1959, I was greeted by my boss, an extremely large woman with a loud Australian accent, who proceeded to cram both of us into a small Austin taxi before heading to the city. This was Elma Kelly, the founder and chairman of Cathay Advertising, which at the time was one of the largest and most aggressive advertising agencies in Asia. |

| The Cathay office was located on Patpong Road, on the top floor of the Gestetner building. There, a staff of approximately 30 created advertising in Thai, Chinese and English languages for a wide range of consumer and travel-related products. In 1959, all the ad agencies in Bangkok, and indeed throughout most of Asia, were run by expatriates. My work at Cathay was interesting, involving client liaison across a wide range of products. One of the clients was the Louis T. Leonowens import company, originally established by the son of Anna Leonowens, tutor to King Chulalongkorn |

and immortalised in Anna and the King of Siam. We also handled a number of airlines, and at the end of 1959, we were awarded the job of launching a brand-new airline – THAI Airways International.

THAI was a joint venture between the Thai government and Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), and initially operated with three DC-6Bs provided by SAS. The management of THAI International consisted mainly of SAS executives, with a Thai chairman and managing director recruited from the Royal Thai Air Force. The cabin staff members were Thai, with Scandinavian supervisors, and some pilots and co-pilots were recruited from the RTAF. As the airline was to commence flights to nine cities throughout Asia on 1st May, 1960, we also prepared advertising to run in the other destination countries.

My boss, who was not married, had a Chinese girlfriend called So So Li. In order to provide for her future, he opened a bar directly opposite our agency called The Red Door. This, one of the first bars on Patpong Road, had achieved a certain notoriety as its female bar-staff members were virtually unbeatable at liar dice!

The Red Door was also patronised by a group of hard-drinking Americans who, after a few drinks, would confess that they were Air America pilots engaged in flying clandestine missions over Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. These men were paid big bucks, but had no official recognition if they failed to return from their missions – which did sometimes happen.

A year after I arrived in Bangkok, my boss, John Weller, left for three months’ home leave, which was the normal arrangement for expatriates. I took over as acting manager, but quickly ran foul of Peter Jamieson, the area managing director from Cathay, Hong Kong, who expected me to do two jobs without any increase in salary.

My client at THAI International, Chris Hundrup, heard about my problems and offered me the job of advertising manager, with full expatriate conditions. These included housing and car allowances, home leave, travel perks and a substantial increase in salary. This I accepted, and I joined THAI International in September, 1960, four months after the airline commenced regional operations. From this date, we dispensed with Cathay Advertising, much to the ire of Jamieson, and placed our advertising direct with the media.

Helping to create the image for a new airline was an exciting experience. My earlier training in the UK and Canada in production, media and research all came in handy when planning our international ad campaigns.

At the time that I joined THAI, the head office was being renovated, and we therefore operated out of the East Asiatic Co. premises next to the Oriental Hotel. As soon as the new premises were completed, we moved to the small, two-storey building on New Road.

While I was pursuing my new career, my wife Pauline had returned to her original profession of schoolteacher. Starting at Mrs. Clayton’s Junior School, she eventually became headmistress of the British School in Bangkok.

My promotion at THAI meant that we could afford to rent a bigger and better house, with two servants, and we decided that it was time to start a family. After a period of uncertainty, Pauline gave birth to our first son, Marc, in December 1961. Marc was delivered at the Bangkok Nursing Home by Dr. Gertie Ettinger, an Austrian Jewish refugee, who, together with her husband, Egon, also a doctor, had arrived in Bangkok before the war and had proceeded to look after many European expatriates.

For recreation, we joined the Royal Bangkok Sports Club located in the centre of town. It offered excellent facilities ranging from tennis and squash to swimming and an 18-hole golf course. I would quite often have lunch by the pool and chat with Jim Thompson, who mysteriously vanished a few years later while on holiday in Malaysia.

My interest in jazz brought me into contact with a number of fellow enthusiasts, and eventually led to the setting up of a Bangkok Jazz Society. At the centre of this group was Joe Bunnag, the wealthy owner of the Trocadero Hotel, which was frequently the venue where we gathered to listen to recorded jazz. Other members included John Hunter, an account executive from Grant Advertising who went on to become one of the most powerful executives at Coca-Cola in Atlanta, and Lucky Thomson, a senior Australian Army officer, who was an accomplished musician.

In early 1962, I was approached by the owner of a large Australian advertising agency regarding a move to Hong Kong. Fortune Advertising handled the Cathay Pacific Airways account throughout Asia, and because of the close relationship between THAI and Cathay Pacific, and THAI’s growing need for a range of advertising agency services throughout the region, it was proposed that Fortune set up a branch in Bangkok to handle THAI. I was keen to explore a new market, and although Pauline would have preferred to remain in Bangkok, I accepted the job of assistant managing director at Fortune, Hong Kong, and we made the move in April, 1962.

While based in Hong Kong, I continued to handle the local THAI international account, and I maintained contact with my former colleagues at the THAI head office. By late 1963, we started to hear rumours from Bangkok that THAI was not happy with the way the account was being handled, and there was a strong possibility that we could lose it. The owner of Fortune, Ken Landell-Jones, told me to hop on a plane and find out what was happening.

THAI was a joint venture between the Thai government and Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), and initially operated with three DC-6Bs provided by SAS. The management of THAI International consisted mainly of SAS executives, with a Thai chairman and managing director recruited from the Royal Thai Air Force. The cabin staff members were Thai, with Scandinavian supervisors, and some pilots and co-pilots were recruited from the RTAF. As the airline was to commence flights to nine cities throughout Asia on 1st May, 1960, we also prepared advertising to run in the other destination countries.

My boss, who was not married, had a Chinese girlfriend called So So Li. In order to provide for her future, he opened a bar directly opposite our agency called The Red Door. This, one of the first bars on Patpong Road, had achieved a certain notoriety as its female bar-staff members were virtually unbeatable at liar dice!

The Red Door was also patronised by a group of hard-drinking Americans who, after a few drinks, would confess that they were Air America pilots engaged in flying clandestine missions over Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. These men were paid big bucks, but had no official recognition if they failed to return from their missions – which did sometimes happen.

A year after I arrived in Bangkok, my boss, John Weller, left for three months’ home leave, which was the normal arrangement for expatriates. I took over as acting manager, but quickly ran foul of Peter Jamieson, the area managing director from Cathay, Hong Kong, who expected me to do two jobs without any increase in salary.

My client at THAI International, Chris Hundrup, heard about my problems and offered me the job of advertising manager, with full expatriate conditions. These included housing and car allowances, home leave, travel perks and a substantial increase in salary. This I accepted, and I joined THAI International in September, 1960, four months after the airline commenced regional operations. From this date, we dispensed with Cathay Advertising, much to the ire of Jamieson, and placed our advertising direct with the media.

Helping to create the image for a new airline was an exciting experience. My earlier training in the UK and Canada in production, media and research all came in handy when planning our international ad campaigns.

At the time that I joined THAI, the head office was being renovated, and we therefore operated out of the East Asiatic Co. premises next to the Oriental Hotel. As soon as the new premises were completed, we moved to the small, two-storey building on New Road.

While I was pursuing my new career, my wife Pauline had returned to her original profession of schoolteacher. Starting at Mrs. Clayton’s Junior School, she eventually became headmistress of the British School in Bangkok.

My promotion at THAI meant that we could afford to rent a bigger and better house, with two servants, and we decided that it was time to start a family. After a period of uncertainty, Pauline gave birth to our first son, Marc, in December 1961. Marc was delivered at the Bangkok Nursing Home by Dr. Gertie Ettinger, an Austrian Jewish refugee, who, together with her husband, Egon, also a doctor, had arrived in Bangkok before the war and had proceeded to look after many European expatriates.

For recreation, we joined the Royal Bangkok Sports Club located in the centre of town. It offered excellent facilities ranging from tennis and squash to swimming and an 18-hole golf course. I would quite often have lunch by the pool and chat with Jim Thompson, who mysteriously vanished a few years later while on holiday in Malaysia.

My interest in jazz brought me into contact with a number of fellow enthusiasts, and eventually led to the setting up of a Bangkok Jazz Society. At the centre of this group was Joe Bunnag, the wealthy owner of the Trocadero Hotel, which was frequently the venue where we gathered to listen to recorded jazz. Other members included John Hunter, an account executive from Grant Advertising who went on to become one of the most powerful executives at Coca-Cola in Atlanta, and Lucky Thomson, a senior Australian Army officer, who was an accomplished musician.

In early 1962, I was approached by the owner of a large Australian advertising agency regarding a move to Hong Kong. Fortune Advertising handled the Cathay Pacific Airways account throughout Asia, and because of the close relationship between THAI and Cathay Pacific, and THAI’s growing need for a range of advertising agency services throughout the region, it was proposed that Fortune set up a branch in Bangkok to handle THAI. I was keen to explore a new market, and although Pauline would have preferred to remain in Bangkok, I accepted the job of assistant managing director at Fortune, Hong Kong, and we made the move in April, 1962.

While based in Hong Kong, I continued to handle the local THAI international account, and I maintained contact with my former colleagues at the THAI head office. By late 1963, we started to hear rumours from Bangkok that THAI was not happy with the way the account was being handled, and there was a strong possibility that we could lose it. The owner of Fortune, Ken Landell-Jones, told me to hop on a plane and find out what was happening.

Left: THAI’s famous logo, designed by Walter Landor & Associates, earned the nickname “jumpee,” a small Thai flower, and also the gentle slang word for a little boy’s winky! Below: Not one of Roy’s ads, but one that’s typical of the times. This one is from Red Cock Whisky, which caused quite a stir with its ‘Happiness is a Red Cock’ slogan.

I arrived at the Bangkok Fortune office at 8.00 a.m. the next day, unannounced, to find the doors locked and no sign of life. Around 9.30 a.m., one or two employees drifted in. Of the manager, there was absolutely no sign. On enquiring of his whereabouts, I was told that he rarely came to the office, and might be found at one of the bars on Patpong Road. Later that day I had a meeting with the marketing director of THAI, during which it was made clear that unless management changes at Fortune were quickly made, the business would go elsewhere.

A similar story also came from other Fortune clients. When this was relayed to Landell-Jones, I was asked to take over the job of managing director and to salvage what I could. After a brief return to Hong Kong to pack up our belongings, the family and I returned to Bangkok where we were fortunate to rent a large, Tudor-style house set in a spacious garden, just minutes away from the office.

We managed to resume a close relationship with THAI, reporting to the new marketing director, a charming and talented Danish gentleman called Neils Lumholdt. Neils was the son of the publisher of one of Denmark’s leading newspapers, who had been a leading figure in the Resistance during the Second World War. Neils was sent to America for his university education: there he developed a lifelong passion for jazz, and played double bass in a jazz group. He spoke at least seven languages fluently, including Thai and Italian.

The initial THAI fleet of DC-6Bs had been augmented with Convair Coronado 990s on loan from SAS and Swissair. With its rapid expansion throughout Asia, THAI now decided to introduce Caravelle aircraft to its fleet, and Fortune was assigned to handle this campaign. A new creative director joined us from Australia, and although somewhat corny in retrospect, the ensuing campaign was successful in meeting its objectives. As Fortune was given more and more work by THAI, we also managed to pick up several new accounts so that, by 1965, Fortune was the second largest agency in Thailand behind the American agency Grant Advertising.

A number of international agencies were operating in Thailand at this time, including Cathay, Marklin and Groarke Advertising. This last agency was run by a frequently inebriated Irishman, who as one of the first to operate an advertising agency in Bangkok after the Second World War, had held, at one time or another, most of the major national accounts. Many of these had been lost as a result of Groarke becoming drunk and abusive to his clients.

The quality of advertising in Thailand improved as the years went by, but there was no shortage of bizarre interpretations to keep us amused. One such was a black-and-white press ad promoting the pharmaceutical, Preparation H. This consisted of a drawing of a gentleman with his backside on fire, and the promise that Preparation H would quell the flames!

Another full-page ad, this time in full colour, promoted Red Cock Thai whisky. It featured a photograph of a beautiful Thai girl reclining beneath a banner headline which stated, in English, “Happiness is a Red Cock.”

Along similar lines was a poster for Guinness Stout. Throughout Asia, Guinness Stout is promoted as a tonic for nursing mothers. In Thailand, this was extended to include fathers, or in this particular case, would-be fathers. The poster featured a voluptuous and scantily clad actress of some note, with a slogan in Thai which translated as “Guinness keeps your pecker up.” There is no record of the reaction from Dublin!

THAI continued to expand at a steady pace. By 1965, the airline was planning new routes to Bali and Kathmandu, plus other destinations, which would eventually result in it providing the most extensive airline network in the east Asia region. I was approached by THAI at this point, for the second time, to return as advertising manager with expanded responsibilities – and an attractive salary and benefits package.

The offer to return to THAI with all its perks was very tempting, especially in view of my growing family, and I therefore made the decision to rejoin the airline at the end of 1965.

During the three-and-a-half years that I had been with Fortune, THAI had grown rapidly, and with the introduction of a fleet of Caravelles and a further expansion of routes, the head office was filled to overflowing. I therefore set up my new advertising department in leased premises alongside the General Post Office on New Road.

Also in our leased building was the public relations department, run by a charming lady by the name of Mrs Chitdee Rangavara. She was soon joined by a PR consultant from London named Robin Dannhorn, who was seconded to THAI by Grant Advertising.

hitdee Rangareva was an unusual Thai lady. She was remarkably outspoken, having spent some years in Australia working for the Thai language channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She was also lots of fun to be with.

Assisting Mrs Chitdee was a serious young Englishman, Robin Dannhorn, who had previously worked at the Financial Times in London. He arrived in Bangkok with his wife and two young children. With his pale complexion, conservative suits and horn-rimmed glasses, Robin looked completely out of place in exotic Thailand, but that was soon to change!

Through Bob Udick, the editor of the Bangkok World newspaper, I also met an American writer named Harold Stephens. He was halfway through driving a Toyota Land Cruiser 42,000 miles around the world, and was looking for a company to sponsor a series of travel articles. This I agreed to do, little realising that Steve would eventually write more than 3,000 articles for the Bangkok World and the Bangkok Post.

We selected Grant Advertising as our regional agency, and I worked closely with their regional vice-president, Michael Brierley, who was based in Singapore.

Back at the head office, one of my major jobs was to create a manual which would be used by all THAI offices to standardise the way in which we presented ourselves to the public. This extended all the way from ticket-office signage, to stationery, baggage labels, and even how to handle correspondence in English. Given the wide range of cultures, languages and customs in the THAI network, this standardisation was critical if we were to be seen as a reliable international airline.

Most of my flights around the region took place during the week, which meant that I could spend the weekends at home. On Saturdays, we would quite often take Marc and Rachel down to the seaside resort of Pattaya. There, we rented a beachside bungalow, joined the Royal Varuna Yacht Club and learnt to sail an Enterprise dinghy. It was at the Varuna Club that we observed the polygamous nature of Thai life, which in spite of claims to have given way to monogamy, still pervaded all strata of Thai society. A popular sailor at the club was Prince Bira, who had enjoyed great success in Europe as a racing-car driver. While Prince Bira was competing in his Enterprise dinghy (and frequently winning), his three wives would enjoy each other’s company on the club house verandah. Only non-Thais were in any way surprised at this relationship.

Towards the end of 1966, Pauline announced that she was pregnant again, and our second son, Andrew, was born at the Bangkok Nursing Home on 27th June, 1967.

Another event occurred in 1967 which caused us much sadness. On a Saturday evening, we attended a dinner hosted by one of the Scandinavian executives, at which my boss, Neils Lumholdt, and my assistant, Roendej, were present, together with an American photographer, Pete Peterson, and his beautiful Swedish assistant, Inge-Marie.

We had arranged an air-to-air photography session for the following morning, for which Pete Peterson and Inge-Marie would fly in an RTAF Beechcraft in order to photograph one of our new Caravelles. My assistant was due to join the flight to supervise the work, and to liaise with the Thai airforce pilot. Neils and I discussed joining the flight, but as the evening wore on, we both decided not to go.

The next day, I received a phone call. I was told that, in trying to get closer to the Caravelle, the Beechcraft had collided with the larger aircraft, losing a wing in the process. This resulted in the death of all our friends. Ironically, the Caravelle was being piloted by Roendej’s cousin, a senior captain called Jothin Pamon-Montri, who, with great skill, managed to land the damaged Caravelle. He went on to become a senior vice-president at THAI.

After the birth of Andy, Pauline and I hit a rough patch in our marriage, and she indicated that she would like to return to live in England.

A similar story also came from other Fortune clients. When this was relayed to Landell-Jones, I was asked to take over the job of managing director and to salvage what I could. After a brief return to Hong Kong to pack up our belongings, the family and I returned to Bangkok where we were fortunate to rent a large, Tudor-style house set in a spacious garden, just minutes away from the office.

We managed to resume a close relationship with THAI, reporting to the new marketing director, a charming and talented Danish gentleman called Neils Lumholdt. Neils was the son of the publisher of one of Denmark’s leading newspapers, who had been a leading figure in the Resistance during the Second World War. Neils was sent to America for his university education: there he developed a lifelong passion for jazz, and played double bass in a jazz group. He spoke at least seven languages fluently, including Thai and Italian.

The initial THAI fleet of DC-6Bs had been augmented with Convair Coronado 990s on loan from SAS and Swissair. With its rapid expansion throughout Asia, THAI now decided to introduce Caravelle aircraft to its fleet, and Fortune was assigned to handle this campaign. A new creative director joined us from Australia, and although somewhat corny in retrospect, the ensuing campaign was successful in meeting its objectives. As Fortune was given more and more work by THAI, we also managed to pick up several new accounts so that, by 1965, Fortune was the second largest agency in Thailand behind the American agency Grant Advertising.

A number of international agencies were operating in Thailand at this time, including Cathay, Marklin and Groarke Advertising. This last agency was run by a frequently inebriated Irishman, who as one of the first to operate an advertising agency in Bangkok after the Second World War, had held, at one time or another, most of the major national accounts. Many of these had been lost as a result of Groarke becoming drunk and abusive to his clients.

The quality of advertising in Thailand improved as the years went by, but there was no shortage of bizarre interpretations to keep us amused. One such was a black-and-white press ad promoting the pharmaceutical, Preparation H. This consisted of a drawing of a gentleman with his backside on fire, and the promise that Preparation H would quell the flames!

Another full-page ad, this time in full colour, promoted Red Cock Thai whisky. It featured a photograph of a beautiful Thai girl reclining beneath a banner headline which stated, in English, “Happiness is a Red Cock.”

Along similar lines was a poster for Guinness Stout. Throughout Asia, Guinness Stout is promoted as a tonic for nursing mothers. In Thailand, this was extended to include fathers, or in this particular case, would-be fathers. The poster featured a voluptuous and scantily clad actress of some note, with a slogan in Thai which translated as “Guinness keeps your pecker up.” There is no record of the reaction from Dublin!

THAI continued to expand at a steady pace. By 1965, the airline was planning new routes to Bali and Kathmandu, plus other destinations, which would eventually result in it providing the most extensive airline network in the east Asia region. I was approached by THAI at this point, for the second time, to return as advertising manager with expanded responsibilities – and an attractive salary and benefits package.

The offer to return to THAI with all its perks was very tempting, especially in view of my growing family, and I therefore made the decision to rejoin the airline at the end of 1965.

During the three-and-a-half years that I had been with Fortune, THAI had grown rapidly, and with the introduction of a fleet of Caravelles and a further expansion of routes, the head office was filled to overflowing. I therefore set up my new advertising department in leased premises alongside the General Post Office on New Road.

Also in our leased building was the public relations department, run by a charming lady by the name of Mrs Chitdee Rangavara. She was soon joined by a PR consultant from London named Robin Dannhorn, who was seconded to THAI by Grant Advertising.

hitdee Rangareva was an unusual Thai lady. She was remarkably outspoken, having spent some years in Australia working for the Thai language channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She was also lots of fun to be with.

Assisting Mrs Chitdee was a serious young Englishman, Robin Dannhorn, who had previously worked at the Financial Times in London. He arrived in Bangkok with his wife and two young children. With his pale complexion, conservative suits and horn-rimmed glasses, Robin looked completely out of place in exotic Thailand, but that was soon to change!

Through Bob Udick, the editor of the Bangkok World newspaper, I also met an American writer named Harold Stephens. He was halfway through driving a Toyota Land Cruiser 42,000 miles around the world, and was looking for a company to sponsor a series of travel articles. This I agreed to do, little realising that Steve would eventually write more than 3,000 articles for the Bangkok World and the Bangkok Post.

We selected Grant Advertising as our regional agency, and I worked closely with their regional vice-president, Michael Brierley, who was based in Singapore.

Back at the head office, one of my major jobs was to create a manual which would be used by all THAI offices to standardise the way in which we presented ourselves to the public. This extended all the way from ticket-office signage, to stationery, baggage labels, and even how to handle correspondence in English. Given the wide range of cultures, languages and customs in the THAI network, this standardisation was critical if we were to be seen as a reliable international airline.

Most of my flights around the region took place during the week, which meant that I could spend the weekends at home. On Saturdays, we would quite often take Marc and Rachel down to the seaside resort of Pattaya. There, we rented a beachside bungalow, joined the Royal Varuna Yacht Club and learnt to sail an Enterprise dinghy. It was at the Varuna Club that we observed the polygamous nature of Thai life, which in spite of claims to have given way to monogamy, still pervaded all strata of Thai society. A popular sailor at the club was Prince Bira, who had enjoyed great success in Europe as a racing-car driver. While Prince Bira was competing in his Enterprise dinghy (and frequently winning), his three wives would enjoy each other’s company on the club house verandah. Only non-Thais were in any way surprised at this relationship.

Towards the end of 1966, Pauline announced that she was pregnant again, and our second son, Andrew, was born at the Bangkok Nursing Home on 27th June, 1967.

Another event occurred in 1967 which caused us much sadness. On a Saturday evening, we attended a dinner hosted by one of the Scandinavian executives, at which my boss, Neils Lumholdt, and my assistant, Roendej, were present, together with an American photographer, Pete Peterson, and his beautiful Swedish assistant, Inge-Marie.

We had arranged an air-to-air photography session for the following morning, for which Pete Peterson and Inge-Marie would fly in an RTAF Beechcraft in order to photograph one of our new Caravelles. My assistant was due to join the flight to supervise the work, and to liaise with the Thai airforce pilot. Neils and I discussed joining the flight, but as the evening wore on, we both decided not to go.

The next day, I received a phone call. I was told that, in trying to get closer to the Caravelle, the Beechcraft had collided with the larger aircraft, losing a wing in the process. This resulted in the death of all our friends. Ironically, the Caravelle was being piloted by Roendej’s cousin, a senior captain called Jothin Pamon-Montri, who, with great skill, managed to land the damaged Caravelle. He went on to become a senior vice-president at THAI.

After the birth of Andy, Pauline and I hit a rough patch in our marriage, and she indicated that she would like to return to live in England.

With three small children, she was already planning ahead for their education and did not want to have to send them away – a common occurrence with so many expatriates. It was agreed that I would continue with my work at THAI, which I enjoyed, and Pauline and the children moved to Cornwall.

Neils subsequently offered to share his house with me, which I gladly accepted. There followed a hectic period of some months, which was entertaining, but which did my liver very little good, I suspect. Neils loved to party, and our evening excursions would frequently end up at Klongtoi, the dock area, where crews from Scandinavian ships drank themselves into oblivion. We also patronised a restaurant called The Two Vikings. It was run by two gay, former SAS stewards, and served wonderful gravlax and ice-cold aquavit.

Under the guidance of Neils, THAI had grown to become one of the largest airlines in Asia, and one of the most profitable. In 1967, we launched the first jet service to Bali, which up to that time had been mainly served by the occasional cruise liner. Prior to the start of this new service, I visited this island paradise, with its beautiful women and unique works of art.

In 1968, we introduced the first jet service to Kathmandu.

The expansion of our routenet meant that we needed longer-range aircraft. Orders were therefore placed with the McDonnell Douglas Corporation for new DC8 aircraft.

My work at THAI continued to be interesting and rewarding, but I was missing my children, in spite of frequent trips back to the UK. In late 1968, I decided to resign from THAI and look for a job in England.

Although I had moved to the other side of the world, I was still involved with the airline. As the director of a large UK ad agency, THAI had very kindly given me the responsibility for its advertising in the UK.

In 1973, THAI started DC8-33 flights to Copenhagen, followed by London, Paris and Frankfurt. I became more heavily involved with the promotion of THAI in Europe, and met with Neils Lumholdt on a regular basis.

round mid-1975, Neils invited me to lunch and asked if I would be interested in returning to the THAI head office as marketing development manager.

n my arrival in Bangkok, I was impressed with the growth of THAI, which had recently undergone a complete corporate-identity facelift created by Walter Landor & Associates. The sales director of THAI, Chatrachai Bunya-Ananta, suggested that I prepare a reorganisation plan and operating budget for the marketing development department, which I completed in two days.

To my surprise, the plan and budget were approved, and I was offered the job to start as soon as possible. This marked the third time that I would be employed by THAI, which probably stands as a record, as the company policy was not to employ anyone more than once.

One of my first jobs was to fire the agency and take all of their work in-house. I also terminated the existing contract for THAI’s in-flight magazine, Sawasdee, which we had originally created in the mid-1960s as an in-house publication. Working together with THAI’s public relations director, Khun Chitdee, we reassigned editorial and art direction responsibilities to a team in Hong Kong, while taking charge of the advertising sales and production.

To handle the significant increase in workload, I recruited a number of staff from advertising agencies in Bangkok. My assistant was Sam Peck, a laid-back Californian who had joined THAI from the SAS organisation in the USA. Sam was a talented photographer who made frequent trips around the THAI network, to add to our newly created photo files. He also added a number of attractive Thai air hostesses to his dating list, as he was a good-looking and charming man. I also recruited Sommit Barpuyawart, who had recently returned from the UK, as my Art director.

Having dispensed with the services of our previous advertising agency, we needed to find a new creative team to produce top-quality campaigns to be placed by our in-house media department. As an international airline, we were not restricted to Bangkok, and I therefore started to research agencies in Europe, the USA, Asia and Australia.

My final recommendation came down to two agencies in Sydney, and it was decided to appoint the relatively new agency of Magnus, Nankervis & Curl.

When I left THAI in 1968, our advertising was strongly focused on the unique Thai brand of in-flight service, which was, rightly, judged to be the best in Asia. Following my departure, Neils decided to adopt a trendier advertising approach, with the slogan Get Into It, which promoted the exciting new destinations in the THAI network and the expanded fleet of new aircraft.

Throughout the ’60s, Cathay Pacific was the leading airline in southern Asia, but THAI undoubtedly had the best reputation for in-flight food and service. At this time, Malaysian and Singapore Airlines had experimented with a joint venture, which ultimately failed, but it was competition from within Thailand which allowed Singapore Airlines to assume the dominant position in the region.

Prince Nicky Varanond, chief pilot at THAI, decided to launch a competitive airline named Air Siam. Having secured influential backers and leased Airbus equipment, Air Siam, with discounted fares, proceeded to engage THAI in a destructive battle for air-traffic rights. This confrontation eventually led to a total strike by THAI staff, and Air Siam subsequently self-destructed. While this battle was consuming the energies of the THAI management, Singapore Airlines, with strong backing from the Singapore government, stormed ahead of THAI to assume the premier position among the world’s airlines.

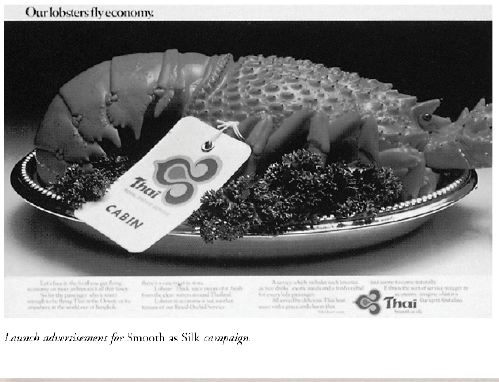

Air Siam collapsed shortly after I returned to THAI, and my advertising recommendation to Neils Lumholdt was to get back to the core values which had proven to be so successful for THAI in the past. With the assistance of Trevor Harrison, a research consultant for Magnus, Nankervis & Curl, we conducted a number of focus groups in Asia and Australia, to determine the factors which most influenced air travellers when selecting an airline. Not surprisingly, in-flight service emerged as an important factor with members of these groups. Armed with this information, John Nankervis and Ted Curl, together with their creative teams, created a campaign built around the theme Smooth as Silk, which proved to be highly effective in projecting THAI as a leader in in-flight service and efficiency.

A major development for THAI was the introduction of Boeing 747 jumbo jets in 1979 and 1980. The campaign to launch THAI’s Jumbos provided many opportunities to link Thailand’s revered animals in humorous ways.

I met many interesting people during my years in Thailand, one of whom was the Swiss artist Theo Meier. The son of a banker, he had left Switzerland in 1932 with an easel on his back, to travel and paint in the South Seas and Asia. He eventually settled in Bali before the war, at a time when few people knew of this island paradise with its beautiful, bare-breasted women and man-made rice terraces. Theo stayed in Bali for 22 years, painting wonderful portraits and landscapes. He also became an authority on Balinese music. After the downfall of President Sukarno, Theo decided to move to Chiang Mai, where I was introduced to him and his new Thai wife, Laiad.

In 1982, I paused to consider my options for the future. Back in 1977, the Thai partners had bought out the remaining shares in THAI from SAS, and gradually over the intervening years, the European executives had been replaced by Thai managers. My own position in THAI was not affected by these changes, but I could visualise a time when I would be increasingly isolated in a company which now employed more than 8,000 Thai personnel.

In essence, I proposed that we set up a new advertising agency, based in Hong Kong, to handle THAI’s worldwide creative and production work. I had discussed this with my boss, Chatrachai Bunya-Ananta, and although he could not make an absolute commitment, I considered it a risk worth taking. Hence, we agreed to set up MNC & Howard, and I resigned from THAI – for the third and last time!

MNC & Howard was appointed to handle THAI’s advertising, which continued until 1995, while a sister company produced Sawasdee magazine for the same period.

Neils subsequently offered to share his house with me, which I gladly accepted. There followed a hectic period of some months, which was entertaining, but which did my liver very little good, I suspect. Neils loved to party, and our evening excursions would frequently end up at Klongtoi, the dock area, where crews from Scandinavian ships drank themselves into oblivion. We also patronised a restaurant called The Two Vikings. It was run by two gay, former SAS stewards, and served wonderful gravlax and ice-cold aquavit.

Under the guidance of Neils, THAI had grown to become one of the largest airlines in Asia, and one of the most profitable. In 1967, we launched the first jet service to Bali, which up to that time had been mainly served by the occasional cruise liner. Prior to the start of this new service, I visited this island paradise, with its beautiful women and unique works of art.

In 1968, we introduced the first jet service to Kathmandu.

The expansion of our routenet meant that we needed longer-range aircraft. Orders were therefore placed with the McDonnell Douglas Corporation for new DC8 aircraft.

My work at THAI continued to be interesting and rewarding, but I was missing my children, in spite of frequent trips back to the UK. In late 1968, I decided to resign from THAI and look for a job in England.

Although I had moved to the other side of the world, I was still involved with the airline. As the director of a large UK ad agency, THAI had very kindly given me the responsibility for its advertising in the UK.

In 1973, THAI started DC8-33 flights to Copenhagen, followed by London, Paris and Frankfurt. I became more heavily involved with the promotion of THAI in Europe, and met with Neils Lumholdt on a regular basis.

round mid-1975, Neils invited me to lunch and asked if I would be interested in returning to the THAI head office as marketing development manager.

n my arrival in Bangkok, I was impressed with the growth of THAI, which had recently undergone a complete corporate-identity facelift created by Walter Landor & Associates. The sales director of THAI, Chatrachai Bunya-Ananta, suggested that I prepare a reorganisation plan and operating budget for the marketing development department, which I completed in two days.

To my surprise, the plan and budget were approved, and I was offered the job to start as soon as possible. This marked the third time that I would be employed by THAI, which probably stands as a record, as the company policy was not to employ anyone more than once.

One of my first jobs was to fire the agency and take all of their work in-house. I also terminated the existing contract for THAI’s in-flight magazine, Sawasdee, which we had originally created in the mid-1960s as an in-house publication. Working together with THAI’s public relations director, Khun Chitdee, we reassigned editorial and art direction responsibilities to a team in Hong Kong, while taking charge of the advertising sales and production.

To handle the significant increase in workload, I recruited a number of staff from advertising agencies in Bangkok. My assistant was Sam Peck, a laid-back Californian who had joined THAI from the SAS organisation in the USA. Sam was a talented photographer who made frequent trips around the THAI network, to add to our newly created photo files. He also added a number of attractive Thai air hostesses to his dating list, as he was a good-looking and charming man. I also recruited Sommit Barpuyawart, who had recently returned from the UK, as my Art director.

Having dispensed with the services of our previous advertising agency, we needed to find a new creative team to produce top-quality campaigns to be placed by our in-house media department. As an international airline, we were not restricted to Bangkok, and I therefore started to research agencies in Europe, the USA, Asia and Australia.

My final recommendation came down to two agencies in Sydney, and it was decided to appoint the relatively new agency of Magnus, Nankervis & Curl.

When I left THAI in 1968, our advertising was strongly focused on the unique Thai brand of in-flight service, which was, rightly, judged to be the best in Asia. Following my departure, Neils decided to adopt a trendier advertising approach, with the slogan Get Into It, which promoted the exciting new destinations in the THAI network and the expanded fleet of new aircraft.

Throughout the ’60s, Cathay Pacific was the leading airline in southern Asia, but THAI undoubtedly had the best reputation for in-flight food and service. At this time, Malaysian and Singapore Airlines had experimented with a joint venture, which ultimately failed, but it was competition from within Thailand which allowed Singapore Airlines to assume the dominant position in the region.

Prince Nicky Varanond, chief pilot at THAI, decided to launch a competitive airline named Air Siam. Having secured influential backers and leased Airbus equipment, Air Siam, with discounted fares, proceeded to engage THAI in a destructive battle for air-traffic rights. This confrontation eventually led to a total strike by THAI staff, and Air Siam subsequently self-destructed. While this battle was consuming the energies of the THAI management, Singapore Airlines, with strong backing from the Singapore government, stormed ahead of THAI to assume the premier position among the world’s airlines.

Air Siam collapsed shortly after I returned to THAI, and my advertising recommendation to Neils Lumholdt was to get back to the core values which had proven to be so successful for THAI in the past. With the assistance of Trevor Harrison, a research consultant for Magnus, Nankervis & Curl, we conducted a number of focus groups in Asia and Australia, to determine the factors which most influenced air travellers when selecting an airline. Not surprisingly, in-flight service emerged as an important factor with members of these groups. Armed with this information, John Nankervis and Ted Curl, together with their creative teams, created a campaign built around the theme Smooth as Silk, which proved to be highly effective in projecting THAI as a leader in in-flight service and efficiency.

A major development for THAI was the introduction of Boeing 747 jumbo jets in 1979 and 1980. The campaign to launch THAI’s Jumbos provided many opportunities to link Thailand’s revered animals in humorous ways.

I met many interesting people during my years in Thailand, one of whom was the Swiss artist Theo Meier. The son of a banker, he had left Switzerland in 1932 with an easel on his back, to travel and paint in the South Seas and Asia. He eventually settled in Bali before the war, at a time when few people knew of this island paradise with its beautiful, bare-breasted women and man-made rice terraces. Theo stayed in Bali for 22 years, painting wonderful portraits and landscapes. He also became an authority on Balinese music. After the downfall of President Sukarno, Theo decided to move to Chiang Mai, where I was introduced to him and his new Thai wife, Laiad.

In 1982, I paused to consider my options for the future. Back in 1977, the Thai partners had bought out the remaining shares in THAI from SAS, and gradually over the intervening years, the European executives had been replaced by Thai managers. My own position in THAI was not affected by these changes, but I could visualise a time when I would be increasingly isolated in a company which now employed more than 8,000 Thai personnel.

In essence, I proposed that we set up a new advertising agency, based in Hong Kong, to handle THAI’s worldwide creative and production work. I had discussed this with my boss, Chatrachai Bunya-Ananta, and although he could not make an absolute commitment, I considered it a risk worth taking. Hence, we agreed to set up MNC & Howard, and I resigned from THAI – for the third and last time!

MNC & Howard was appointed to handle THAI’s advertising, which continued until 1995, while a sister company produced Sawasdee magazine for the same period.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed