Despite the international awards and celebrity status, Prateep Unsongtham Hata continues a lifelong battle to improve the lives of her fellow residents in Klong Toey

By Maxmilian Wechsler

By Maxmilian Wechsler

| SHE is one of Thailand’s most recognized personalities, but unlike the vast majority of ‘celebs,’ it’s not because of her involvement in movies, music or even politics. Prateep Ungsongtham Hata has earned widespread recognition and awards through her work to help poor people in Bangkok’s sprawling Klong Toey community where she was born and has lived all her life. The former senator for Bangkok is the secretary-general of the Duang Prateep Foundation (DPF), which she founded in 1978. Living and working as she does in the Klong Toey slum, Mrs Prateep has seen much more than her share of the hard side of life, but when she speaks about her work, politics, Thailand or any other subject, she is full of energy and optimism. There’s something very special about her, and her nickname of “Slum Angel” seems most appropriate. Even people who disagree with her political views and affiliations tend to genuinely respect her for her achievements and hard |

work for the poor. I first met Mrs Prateep many years ago, and since that time there has been no change in her spirit, attitude or behavior. Through her foundation Mrs Prateep has helped thousands of underprivileged people, especially children, and for that she has received praise and awards from governments and international organizations.

In Thailand she is immensely popular and somewhat of a celebrity, not only in Klong Toey but throughout Bangkok and also up-country. A walk through a Bangkok shopping mall invariably attracts considerable attention, with people asking friendly questions or wishing her well. Parents tell their children to say “sawadee” or to wai her. It’s an incredible reception for someone who’s not in the entertainment business. Far from it: her mission is very serious, but she approaches it with grace and good humor.

Early life

Mrs Prateep was born and raised in Klong Toey. As a youngster, she took on all kinds of jobs to help her family financially, including chipping rust from the sides of ships in the port and selling sweets. Early on she became devoted to helping her neighbours in Klong Toey with their difficulties, and in 1976, at the age of 24, she established the DPF as a formal instrument for improving the community. The foundation runs many projects in the areas of education, child abuse, HIV/Aids, and welfare of the elderly and youths living in the slum.

Her good work caught the attention of people worldwide. In 1978, Mrs Prateep won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service. Two years later she received the John D. Rockefeller Youth Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mankind. With the prize money she established the Foundation for Slum Child Care. In 2004 she received the World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child and the Global Friends’ Award.

In 2000 she was elected to the Thai Senate representing Bangkok and served on several government committees, but lost her seat following the military coup in September 2006.

Over the years many foreigners have volunteered to work at the foundation, including the man who was to become Mrs Prateep’s husband, Professor Dr Tatsuya Hata, who is a full-time lecturer at Kinki University in Osaka. He came to Thailand in the early 1970s with a group of volunteers to help Cambodian refugees along the Thai-Cambodian border. After visiting Mrs Prateep in Klong Toey, they fell in love and married in 1987. The wedding received a lot of media attention in Thailand and Japan. The couple has two sons.

In Thailand she is immensely popular and somewhat of a celebrity, not only in Klong Toey but throughout Bangkok and also up-country. A walk through a Bangkok shopping mall invariably attracts considerable attention, with people asking friendly questions or wishing her well. Parents tell their children to say “sawadee” or to wai her. It’s an incredible reception for someone who’s not in the entertainment business. Far from it: her mission is very serious, but she approaches it with grace and good humor.

Early life

Mrs Prateep was born and raised in Klong Toey. As a youngster, she took on all kinds of jobs to help her family financially, including chipping rust from the sides of ships in the port and selling sweets. Early on she became devoted to helping her neighbours in Klong Toey with their difficulties, and in 1976, at the age of 24, she established the DPF as a formal instrument for improving the community. The foundation runs many projects in the areas of education, child abuse, HIV/Aids, and welfare of the elderly and youths living in the slum.

Her good work caught the attention of people worldwide. In 1978, Mrs Prateep won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service. Two years later she received the John D. Rockefeller Youth Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mankind. With the prize money she established the Foundation for Slum Child Care. In 2004 she received the World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child and the Global Friends’ Award.

In 2000 she was elected to the Thai Senate representing Bangkok and served on several government committees, but lost her seat following the military coup in September 2006.

Over the years many foreigners have volunteered to work at the foundation, including the man who was to become Mrs Prateep’s husband, Professor Dr Tatsuya Hata, who is a full-time lecturer at Kinki University in Osaka. He came to Thailand in the early 1970s with a group of volunteers to help Cambodian refugees along the Thai-Cambodian border. After visiting Mrs Prateep in Klong Toey, they fell in love and married in 1987. The wedding received a lot of media attention in Thailand and Japan. The couple has two sons.

Klong Toey slum

Klong Toey slum covers an area of about two square kilometers and is home to an estimated 100,000 people, according to Mrs Prateep. It is the biggest and one of the oldest slums in Thailand. The National Housing Authority reported a few years ago there are about 5,500 slum communities throughout the country.

Klong Toey slum dates back to the early 1950s when impoverished rural migrants, mainly from the Northeast, came to Bangkok looking for a better life. Some of them were employed by the Port Authority of Thailand (PAT) on construction projects at the Bangkok port. They formed a makeshift community and after the work was completed many of them decided to stay.

“The immigrants could find work on a daily basis in the port, loading and unloading ships or at one of four nearby oil refineries Bangchak, Caltex, PTT and Shell. They could also find work at Klong Toey market, where farmers from more than 30 provinces bring their produce, or in constructions, in small factories or as street vendors,” explained Mrs Prateep.

Numerous improvements have been made in the basic infrastructure of the Klong Toey slum over the years. “Before, the walkways were made of wood, but now they are almost all concrete. Before, we didn’t have an adequate water supply and there weren’t enough electricity connections, but now we have plenty of running water and electricity is supplied everywhere. The slum residents have also changed; now there are many who came from neighboring countries like Myanmar and Cambodia.”

Mrs Prateep noted that the land on which Klong Toey slum is located belongs to the PAT, but noted: “They can’t evict the 100,000 people living here.”

Despite the vast number of inhabitants, the Klong Toey community lacks the air of danger that fills the slums of Manila, Rio de Janeiro and other mega cities. Generally, outsiders are easily accepted – provided they don’t take photos of the residents.

“People might be surprised to learn how little crime there is here,” said Mrs Prateep. “Usually it involves minor offences like stealing laundry from washing lines, especially jeans, mostly by drug addicts. The lines are strung high up so the thieves can’t reach them easily.

“We don’t have big mafia here, only small crooks. You can see some people with tattoos all over their bodies. They look scary but are actually harmless. They are not dangerous or cruel and we can communicate with them.”

She does not deny there is a problem with illegal drugs and addiction in Klong Toey, but says: “Only small quantities of drugs like ya ba

(methamphetamine) pills, ‘ice’ (crystal methamphetamine) or marijuana are available here. The police will usually make the big busts of narcotics outside the slum – maybe one or two million ya ba pills outside the slum compared to just 1,000 or 2,000 pills seized inside the slum. This is a big difference.”

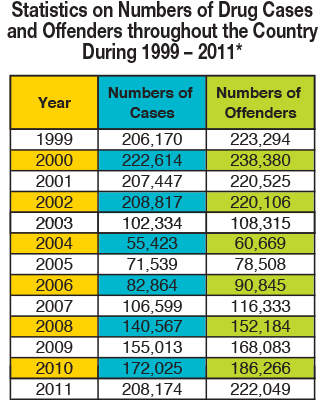

Mrs Prateep said that in all the years she has been in Klong Toey, only the government of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (2002-2006) was able to really make a dent in the drug trade. “When he was prime minister, drugs, addicts, pushers and drug mafia almost disappeared from Klong Toey slum, and it was reduced drastically throughout Thailand as well. This is a fact. Official statistics from the Office of the Narcotic Control Board clearly show the trend then and now (see box).

“Especially during 2004 and 2005, the price of ya ba skyrocketed, to over 300 baht per pill. It was very difficult to find any drugs at all here, so the number of addicts plummeted. Sadly, following the 2006 military coup, ya ba came back, the price dropped, other types of drugs appeared and the number of addicts increased. Since then there has been a small improvement here and throughout the country, but the situation remains serious. Just look at the news now on the number of big drug busts,” Mrs Prateep said. “It wasn’t only the illegal drugs that the Thaksin government reduced, but also the sale of cigarettes and alcohol to minors,” she added.

“We don’t see as many policemen as in the past patrolling inside Klong Toey slum, because during the past six years they have been assigned to maintain security for demonstrations instead of combating crime. There used to be many motorcycle patrols around here, but now there are very few.”

Changing the subject, Mrs Prateep went on: “We have Westerners living in the slum. Some work for different religious organizations. They rent a small room or house to enable them to be close to their followers. They organize various activities according to their faith and so on. There are also some homeless foreigners living in the slum, but not so many. Most of them live on the sidewalks.”

Klong Toey slum covers an area of about two square kilometers and is home to an estimated 100,000 people, according to Mrs Prateep. It is the biggest and one of the oldest slums in Thailand. The National Housing Authority reported a few years ago there are about 5,500 slum communities throughout the country.

Klong Toey slum dates back to the early 1950s when impoverished rural migrants, mainly from the Northeast, came to Bangkok looking for a better life. Some of them were employed by the Port Authority of Thailand (PAT) on construction projects at the Bangkok port. They formed a makeshift community and after the work was completed many of them decided to stay.

“The immigrants could find work on a daily basis in the port, loading and unloading ships or at one of four nearby oil refineries Bangchak, Caltex, PTT and Shell. They could also find work at Klong Toey market, where farmers from more than 30 provinces bring their produce, or in constructions, in small factories or as street vendors,” explained Mrs Prateep.

Numerous improvements have been made in the basic infrastructure of the Klong Toey slum over the years. “Before, the walkways were made of wood, but now they are almost all concrete. Before, we didn’t have an adequate water supply and there weren’t enough electricity connections, but now we have plenty of running water and electricity is supplied everywhere. The slum residents have also changed; now there are many who came from neighboring countries like Myanmar and Cambodia.”

Mrs Prateep noted that the land on which Klong Toey slum is located belongs to the PAT, but noted: “They can’t evict the 100,000 people living here.”

Despite the vast number of inhabitants, the Klong Toey community lacks the air of danger that fills the slums of Manila, Rio de Janeiro and other mega cities. Generally, outsiders are easily accepted – provided they don’t take photos of the residents.

“People might be surprised to learn how little crime there is here,” said Mrs Prateep. “Usually it involves minor offences like stealing laundry from washing lines, especially jeans, mostly by drug addicts. The lines are strung high up so the thieves can’t reach them easily.

“We don’t have big mafia here, only small crooks. You can see some people with tattoos all over their bodies. They look scary but are actually harmless. They are not dangerous or cruel and we can communicate with them.”

She does not deny there is a problem with illegal drugs and addiction in Klong Toey, but says: “Only small quantities of drugs like ya ba

(methamphetamine) pills, ‘ice’ (crystal methamphetamine) or marijuana are available here. The police will usually make the big busts of narcotics outside the slum – maybe one or two million ya ba pills outside the slum compared to just 1,000 or 2,000 pills seized inside the slum. This is a big difference.”

Mrs Prateep said that in all the years she has been in Klong Toey, only the government of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (2002-2006) was able to really make a dent in the drug trade. “When he was prime minister, drugs, addicts, pushers and drug mafia almost disappeared from Klong Toey slum, and it was reduced drastically throughout Thailand as well. This is a fact. Official statistics from the Office of the Narcotic Control Board clearly show the trend then and now (see box).

“Especially during 2004 and 2005, the price of ya ba skyrocketed, to over 300 baht per pill. It was very difficult to find any drugs at all here, so the number of addicts plummeted. Sadly, following the 2006 military coup, ya ba came back, the price dropped, other types of drugs appeared and the number of addicts increased. Since then there has been a small improvement here and throughout the country, but the situation remains serious. Just look at the news now on the number of big drug busts,” Mrs Prateep said. “It wasn’t only the illegal drugs that the Thaksin government reduced, but also the sale of cigarettes and alcohol to minors,” she added.

“We don’t see as many policemen as in the past patrolling inside Klong Toey slum, because during the past six years they have been assigned to maintain security for demonstrations instead of combating crime. There used to be many motorcycle patrols around here, but now there are very few.”

Changing the subject, Mrs Prateep went on: “We have Westerners living in the slum. Some work for different religious organizations. They rent a small room or house to enable them to be close to their followers. They organize various activities according to their faith and so on. There are also some homeless foreigners living in the slum, but not so many. Most of them live on the sidewalks.”

Duang Prateep Foundation

Mrs Prateep’s foundation is currently involved in several projects, sponsoring education, kindergartens, HIV/Aids treatment, credit union and assistance for the old and young. Details about these projects and other information are on the DPF website: www.dpf.or.th. The website is in four languages – Thai, English Japanese and German.

“We also have a number of training programs. For example, we train people in fire protection and also on how to make playgrounds for the slum kids. We train young people who aren’t going to school in various skills so they can become more valuable in the job market and make better money.

“Before there were many fires in the Klong Toey slum but now there aren’t many. One reason is that we train young people and also women on what to do when a fire occurs and how to prevent it from spreading.

“We have some small fire trucks in the slum. The operators are volunteers. In fact, within few days we will receive another small fire truck with hoses and other equipment to combat fires in this crowded environment. Big trucks can’t enter many areas in the slum.

“As for water supply when a fire occurs, we don’t have hydrants like you see on the streets of Bangkok, but we have a supply of dirty water that can be used to combat fire. We are always prepared for emergency situations such as fires.”

Mrs Prateep said that the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration is very active in Klong Toey to prevent disease carried by mosquitoes. “We have very few dengue fever cases here, and no malaria. We are running a program to deal with Aids issues. The number of infected people is not as high as it was in the late 1990s,” she said.

Highlights and disappointments

Asked about her biggest achievements and biggest disappointments, Mrs Prateep replied: “In the past we didn’t have schools in the slum. In the beginning, I opened an illegal school. It took 10 years before it was accepted by the government. I am very proud of this. Also, I am happy that now water and electricity are available to slum dwellers. Of course, I didn’t do it all by myself, but with help and support from many people.

“We can certainly improve the education system for poor children in the slum, she added. There are many children born in this and other slums in Bangkok who don’t have birth certificates and so aren’t able to access the education system. Those children should also have a chance to go to school and receive a proper education. The mothers often don’t have birth certificates or house registration numbers themselves, and many children don’t have birth certificates because they weren’t born in a hospital. The mothers may not be able to afford it. Sometimes this is difficult for the Thai authorities to understand.”

An unforgettable experience, said Mrs Prateep, was meeting with the Dalai Lama in Japan seven years ago. “We were both attending a seminar and staying in the same area, and I had a chance to speak with him.

“As for disappointments, I have had many, but the biggest is that Thailand still has not achieved real democracy. Therefore, there are many problems that can’t be solved in the long term. When we achieve something, as in the drug prevention and suppression I mentioned before, things return to the way they were under another administration.”

What about her venture into politics? “In 2000 I was elected to the Senate. I lost the position following the military coup in September 2006. You asked me if I am going to run for a Senate seat in the next elections due next year. I don’t think so because it will be a waste of time. There’s only a slim chance to win a seat because of the current Constitution. The whole of Bangkok has only one seat to be chosen by the electorate, so it would be very difficult.”

According to the Constitution of Thailand drafted by the military-led interim government in 2007, the Senate is composed of 150 senators, with one directly elected from each of the 76 Thai provinces and the remaining 74 appointed by seven member Senate Selection Committees.

At any rate, said Mrs Prateep, she has plenty of work to do. “I will continue to hold the position of chairman of the foundation until I am 65 years old, in line with the foundation regulations. Afterward, I can be an adviser. As for our funding, it is always a struggle,” she said without elaborating.

“I don’t think the Klong Toey slum will be here forever. The current government has designated an area to build housing for the slum people. If they are satisfied with the new accommodation, they will be free to move there.”

Mrs Prateep’s foundation is currently involved in several projects, sponsoring education, kindergartens, HIV/Aids treatment, credit union and assistance for the old and young. Details about these projects and other information are on the DPF website: www.dpf.or.th. The website is in four languages – Thai, English Japanese and German.

“We also have a number of training programs. For example, we train people in fire protection and also on how to make playgrounds for the slum kids. We train young people who aren’t going to school in various skills so they can become more valuable in the job market and make better money.

“Before there were many fires in the Klong Toey slum but now there aren’t many. One reason is that we train young people and also women on what to do when a fire occurs and how to prevent it from spreading.

“We have some small fire trucks in the slum. The operators are volunteers. In fact, within few days we will receive another small fire truck with hoses and other equipment to combat fires in this crowded environment. Big trucks can’t enter many areas in the slum.

“As for water supply when a fire occurs, we don’t have hydrants like you see on the streets of Bangkok, but we have a supply of dirty water that can be used to combat fire. We are always prepared for emergency situations such as fires.”

Mrs Prateep said that the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration is very active in Klong Toey to prevent disease carried by mosquitoes. “We have very few dengue fever cases here, and no malaria. We are running a program to deal with Aids issues. The number of infected people is not as high as it was in the late 1990s,” she said.

Highlights and disappointments

Asked about her biggest achievements and biggest disappointments, Mrs Prateep replied: “In the past we didn’t have schools in the slum. In the beginning, I opened an illegal school. It took 10 years before it was accepted by the government. I am very proud of this. Also, I am happy that now water and electricity are available to slum dwellers. Of course, I didn’t do it all by myself, but with help and support from many people.

“We can certainly improve the education system for poor children in the slum, she added. There are many children born in this and other slums in Bangkok who don’t have birth certificates and so aren’t able to access the education system. Those children should also have a chance to go to school and receive a proper education. The mothers often don’t have birth certificates or house registration numbers themselves, and many children don’t have birth certificates because they weren’t born in a hospital. The mothers may not be able to afford it. Sometimes this is difficult for the Thai authorities to understand.”

An unforgettable experience, said Mrs Prateep, was meeting with the Dalai Lama in Japan seven years ago. “We were both attending a seminar and staying in the same area, and I had a chance to speak with him.

“As for disappointments, I have had many, but the biggest is that Thailand still has not achieved real democracy. Therefore, there are many problems that can’t be solved in the long term. When we achieve something, as in the drug prevention and suppression I mentioned before, things return to the way they were under another administration.”

What about her venture into politics? “In 2000 I was elected to the Senate. I lost the position following the military coup in September 2006. You asked me if I am going to run for a Senate seat in the next elections due next year. I don’t think so because it will be a waste of time. There’s only a slim chance to win a seat because of the current Constitution. The whole of Bangkok has only one seat to be chosen by the electorate, so it would be very difficult.”

According to the Constitution of Thailand drafted by the military-led interim government in 2007, the Senate is composed of 150 senators, with one directly elected from each of the 76 Thai provinces and the remaining 74 appointed by seven member Senate Selection Committees.

At any rate, said Mrs Prateep, she has plenty of work to do. “I will continue to hold the position of chairman of the foundation until I am 65 years old, in line with the foundation regulations. Afterward, I can be an adviser. As for our funding, it is always a struggle,” she said without elaborating.

“I don’t think the Klong Toey slum will be here forever. The current government has designated an area to build housing for the slum people. If they are satisfied with the new accommodation, they will be free to move there.”

| Prateep Ungsongtham Hata in focus • 1952: Born on August 9 in Klong Toey slum • 1959: Began four years of primary education, at the same time working as a vendor to help with school fees • 1963: Left school to work at a firecracker factory in Klong Toey, chipped rust off ships at the Bangkok Port, and saved money from wages to continue education in evening classes • 1968: Opened an informal school in the slum, continuing her studies at the same time |

• 1970: Awarded a place at Suan Dusit Teacher’s college

• 1976: The Port Authority of Thailand (PAT) posted eviction notices on her home community and her school. Mrs Prateep pushed for a compromise solution and the PAT made a new site available one kilometer away. The government finally recognized her school, called Pattana Village School. Mrs Prateep was appointed principal and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration took over management

• 1978: Received the Magsaysay Award for Public Service. She used the prize money to establish Duang Prateep Foundation, and became its Secretary-General

• 1979: Named outstanding teacher of the year by the Department of Education

• 1980: Left full-time teaching in order to head the Duang Prateep Foundation. Became the first Asian citizen to receive the John D. Rockfeller Youth Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mankind. With the prize money she established the Foundation for Slum Child Care

• 1982: Received a Bachelor’s degree in education from Ban Simdej

Chaopraya Teachers college.

• 1983: The PAT sought to relocate the “Pattana Village Community.” Mrs Prateep persuaded them to enter a land sharing agreement with the slum community and the National Housing Authority (NHA). In August 1985 the entire Pattana Village Community (more than 3,000 people), the school, and the Foundation headquarters moved to a new site

• 1987: Married Dr. Tatsuya Hata PhD, Director of Japan Sotoshu Relief Committee

• 1989: Appointed adviser on urban policy to the Prime Minister. Awarded an Honorary Masters Degree by Ramkhamhaeng University, Bangkok

• 1992: Became a committee member of the Confederation for Democracy and one of the leaders of the opposition to the military dictatorship of the time

• 1993: Appointed to the Parliamentary Advisory Committee on Education for the poor

• 2000: Won a seat in Thailand’s first elected Senate

• 2004: Received the World’s Children’s Prize and the Global Friend’s Award from Queen Silvia of Sweden

• 2005: Received Master’s Degree in Political Science, Sukothai

Thammathirat Open University

• 2007: Honored on U.N International Women’s Day as an Outstanding Woman in Buddhism by an international committee of scholars and

Buddhist clergy. Became chairperson of the Confederation for Democracy

• 2010: One of 13 recipients of the World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child

• 2010: Received “The Golden Scale Award” as an outstanding person on welfare action from the Corrections Center, Ministry of Justice

• 2011: Received the “Heart of Giver” Tara Award

• Present: Mrs Pateep remains as Founder/ Secretary General of Duang Prateep Foundation, Founder/ Committee Member of the Foundation for Slum Child Care, and President of Thai Women’s Empowerment Fund

• 1976: The Port Authority of Thailand (PAT) posted eviction notices on her home community and her school. Mrs Prateep pushed for a compromise solution and the PAT made a new site available one kilometer away. The government finally recognized her school, called Pattana Village School. Mrs Prateep was appointed principal and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration took over management

• 1978: Received the Magsaysay Award for Public Service. She used the prize money to establish Duang Prateep Foundation, and became its Secretary-General

• 1979: Named outstanding teacher of the year by the Department of Education

• 1980: Left full-time teaching in order to head the Duang Prateep Foundation. Became the first Asian citizen to receive the John D. Rockfeller Youth Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mankind. With the prize money she established the Foundation for Slum Child Care

• 1982: Received a Bachelor’s degree in education from Ban Simdej

Chaopraya Teachers college.

• 1983: The PAT sought to relocate the “Pattana Village Community.” Mrs Prateep persuaded them to enter a land sharing agreement with the slum community and the National Housing Authority (NHA). In August 1985 the entire Pattana Village Community (more than 3,000 people), the school, and the Foundation headquarters moved to a new site

• 1987: Married Dr. Tatsuya Hata PhD, Director of Japan Sotoshu Relief Committee

• 1989: Appointed adviser on urban policy to the Prime Minister. Awarded an Honorary Masters Degree by Ramkhamhaeng University, Bangkok

• 1992: Became a committee member of the Confederation for Democracy and one of the leaders of the opposition to the military dictatorship of the time

• 1993: Appointed to the Parliamentary Advisory Committee on Education for the poor

• 2000: Won a seat in Thailand’s first elected Senate

• 2004: Received the World’s Children’s Prize and the Global Friend’s Award from Queen Silvia of Sweden

• 2005: Received Master’s Degree in Political Science, Sukothai

Thammathirat Open University

• 2007: Honored on U.N International Women’s Day as an Outstanding Woman in Buddhism by an international committee of scholars and

Buddhist clergy. Became chairperson of the Confederation for Democracy

• 2010: One of 13 recipients of the World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child

• 2010: Received “The Golden Scale Award” as an outstanding person on welfare action from the Corrections Center, Ministry of Justice

• 2011: Received the “Heart of Giver” Tara Award

• Present: Mrs Pateep remains as Founder/ Secretary General of Duang Prateep Foundation, Founder/ Committee Member of the Foundation for Slum Child Care, and President of Thai Women’s Empowerment Fund

RSS Feed

RSS Feed