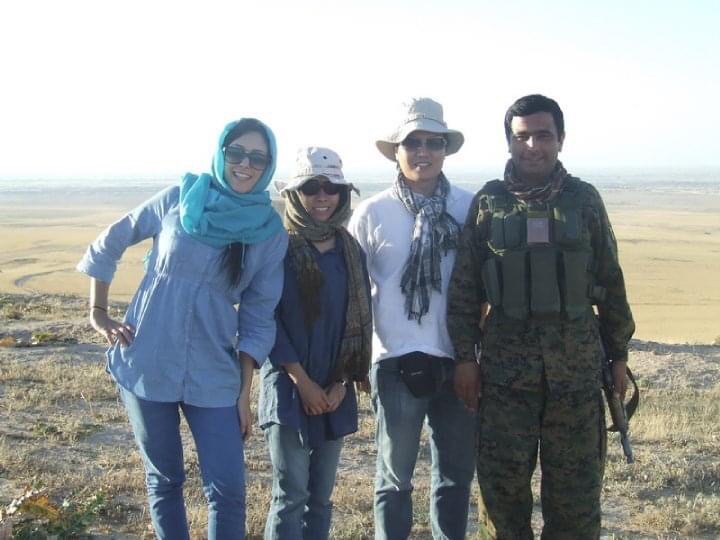

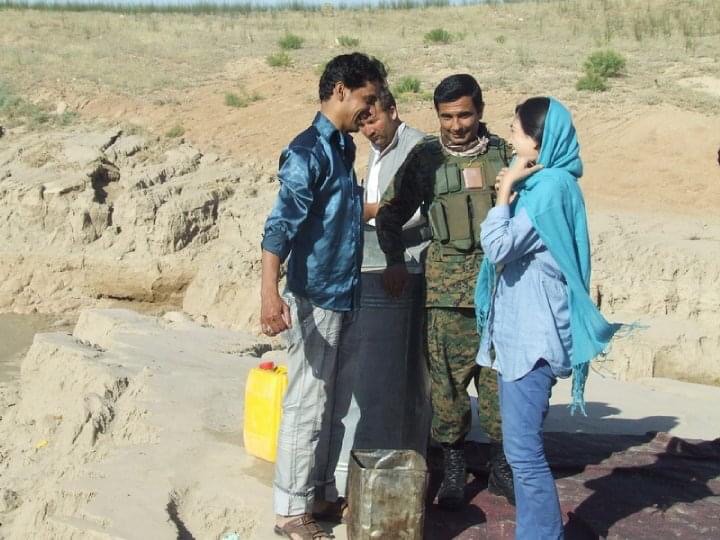

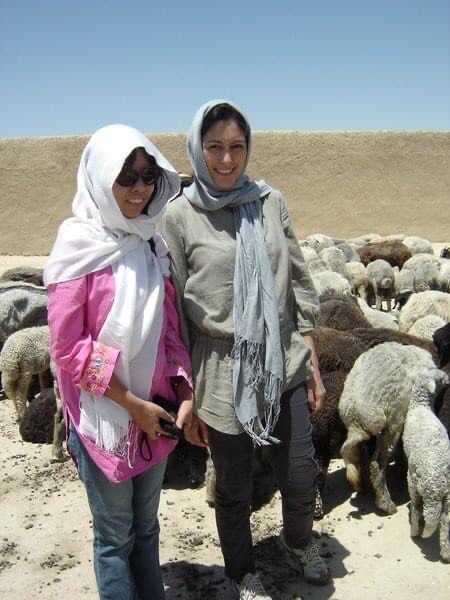

| In a truly remarkable and diverse career, Thai-Australian Jane Holloway has operated in some of the world’s most dangerous regions, explored the root causes of women in transnational organized crime, worked on the campaign to get the Thai prime minister re-elected and now consults for George Soros’s Open Society Foundation on its drug policy program By Colin Hastings She may have only recently turned 40, but Jane Holloway can already look back on an amazing career full of incredible experiences and personal challenges in some of the world’s most notorious hot spots. Her life story reads like an old-style adventure book, with moments requiring great courage and bravery in distant lands, and other times when she welcomed and even relished the difficult situations she often encountered. There is a theme that underpins her entire career and defines Jane’s character – that she can make the world a better place by focusing on issues affecting the status of women not just in her home country of Thailand but across the globe. Motivated by this sense of social responsibility and desire for fair play, Jane has willingly undertaken projects in those faraway lands that few others would consider. And probably nothing demonstrates the inner steel of this outwardly gentle Thai-Australian better than the long periods she spent in Afghanistan, one of the poorest and most deprived places on earth. Based in poppy growing regions in remote Balkh Province near the border with Uzbekistan, bereft of any of the home comforts of Jane’s upbringing, her mission was to work with local warlords and headmen to persuade local farmers to substitute opium cash crops with non-narcotic alternatives. |

The success of this project would eventually achieve another objective - the improvement of the everyday lives of the womenfolk in this traditionally male-dominated society – an outcome that dovetailed perfectly with Jane’s personal agenda.

This experience was great grounding for another of Jane’s overseas adventures. For a year she operated in Myanmar’s remote Kayah State, representing the UNHCR in talks with armed groups and local officials for the safe return of Thailand-based refugees and internally displaced people.

Back on familiar and safer ground in Bangkok, Jane spent the next four years with the Thailand Institute of Justice, eventually becoming its Chief of Crime and Development on a programme highlighting transnational organized crime. This posting gave her the opportunity to work alongside HRH Princess Bajrakitiyabha, eldest daughter of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, on her mission to reform criminal justice in Thailand.

Jane has high praise for the Princess, saying she is always very active and works hard to shed more light on the plight of female prisoners.

Using the US as an example to highlight the link between crime and the structural inequality in society, Jane remarks: “In America most people in prison are the poor, so what drives criminality. You have to ask the question - is prison the solution? Justice has to be fair and equitable. Poor people don’t have the means to pay for lawyers or understand the justice system.”

She then puts the spotlight on the situation in Thailand: “Up to 80% of women in jail are there for drug-related crimes, and of those 60% are mothers, mostly single mothers. What’s the impact on the family?”

Fair sentencing for drug dealers also occupies her mind. “Thailand has extremely harsh laws for drugs and trafficking. Sentences are never reduced – unlike other offences, even murder. In a recent high-profile case, a murderer was released after only nine years of a life sentence. That doesn’t happen to drug offenders.”

Separate research at the Thailand Institute of Justice has shown that many of the Thai women imprisoned in Cambodia are from a troubled background, or abused as kids, or in some cases heart-broken from a failed romance. Nine are single mums who found love with foreign boyfriends and were then prepared to do whatever was asked of them, including operating as drug mules via Cambodia.

Yet another twists in Jane’s amazing career occurred in 2019 when she was recruited by the Phalang Pracharat political party to carry out research that helped Prayut Chan-o-cha’s re-election as Thailand’s prime minister. Jane’s contribution was duly recognized with a call from colleagues for her to stand for election herself. Being apolitical, she politely declined.

“I didn’t know enough about politics. It wasn’t for me,” she says. “I’m much more comfortable behind the scenes. I don’t want to be a public face.”

Jane’s story begins in Bangkok where she was born four decades ago. Aged two, she moved with her family to New Zealand for one year and then to Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, staying there for the next 13 years.

The Holloways eventually returned to Bangkok where Jane attended Ruamrudee International School before leaving again for Australia and studying for her master’s degree in Sydney.

On her return to Thailand, Jane joined the Mae Fah Luang Foundation under Royal Patronage to work on the development project that took her to Afghanistan.

“We were working with 500 families in districts that cultivated opium poppies. If they were opium-free, what could the farmers do instead – that was the challenge,” says Jane. “The answer was to repopulate the area with sheep, which can be used for carpets and food, giving women roles to play in a patriarchal society, so there are all-round benefits.”

Despite the remoteness, the backwardness and the ever-present dangers of the still raging war, Jane was smitten by Afghanistan, “It was the most exciting place – I love the country. There’s something special about working in a war zone – the tanks, the intelligence, the people, the excitement. It’s tribal, dynamic and complicated.”

During this period, Jane also worked for UNHCR, initially in Thailand, profiling the refugee camps in Kanchanabrui and Mae Sot, home for some 140,000 displaced persons from Myanmar. Later she based herself in Kayah State, an area of Myanmar known for its ‘long necked’ tribespeople.

“My role was to identify what would be needed in terms of water and electricity if the refugees returned. I had to deal with government authorities, border police and representatives from seven different ethnic groups. As the only foreigner, I employed small cultural sensitivities liker wearing traditional Burmese clothing while negotiating with these officials.”

Today, Jane is busy with several new projects, including consulting for George Soros’s Open Society Foundation on its drug policy program, based in Bangkok. Another is advising on DragonFly360, a regional platform designed to mobilize society towards gender equality in Asia.

Looking back on her career, Jane says changing jobs so frequently enabled her to remain “relevant.”

“But now, for the first time, I feel I’m slowing down mentally. Today’s technology is complicated and I need to learn so much about social media.

“My motto is to help the most vulnerable in society, which I can do with facts and experience. I saw how elections are run and the political scramble for positions. As I said, I’m much more comfortable behind the scenes.”

This experience was great grounding for another of Jane’s overseas adventures. For a year she operated in Myanmar’s remote Kayah State, representing the UNHCR in talks with armed groups and local officials for the safe return of Thailand-based refugees and internally displaced people.

Back on familiar and safer ground in Bangkok, Jane spent the next four years with the Thailand Institute of Justice, eventually becoming its Chief of Crime and Development on a programme highlighting transnational organized crime. This posting gave her the opportunity to work alongside HRH Princess Bajrakitiyabha, eldest daughter of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, on her mission to reform criminal justice in Thailand.

Jane has high praise for the Princess, saying she is always very active and works hard to shed more light on the plight of female prisoners.

Using the US as an example to highlight the link between crime and the structural inequality in society, Jane remarks: “In America most people in prison are the poor, so what drives criminality. You have to ask the question - is prison the solution? Justice has to be fair and equitable. Poor people don’t have the means to pay for lawyers or understand the justice system.”

She then puts the spotlight on the situation in Thailand: “Up to 80% of women in jail are there for drug-related crimes, and of those 60% are mothers, mostly single mothers. What’s the impact on the family?”

Fair sentencing for drug dealers also occupies her mind. “Thailand has extremely harsh laws for drugs and trafficking. Sentences are never reduced – unlike other offences, even murder. In a recent high-profile case, a murderer was released after only nine years of a life sentence. That doesn’t happen to drug offenders.”

Separate research at the Thailand Institute of Justice has shown that many of the Thai women imprisoned in Cambodia are from a troubled background, or abused as kids, or in some cases heart-broken from a failed romance. Nine are single mums who found love with foreign boyfriends and were then prepared to do whatever was asked of them, including operating as drug mules via Cambodia.

Yet another twists in Jane’s amazing career occurred in 2019 when she was recruited by the Phalang Pracharat political party to carry out research that helped Prayut Chan-o-cha’s re-election as Thailand’s prime minister. Jane’s contribution was duly recognized with a call from colleagues for her to stand for election herself. Being apolitical, she politely declined.

“I didn’t know enough about politics. It wasn’t for me,” she says. “I’m much more comfortable behind the scenes. I don’t want to be a public face.”

Jane’s story begins in Bangkok where she was born four decades ago. Aged two, she moved with her family to New Zealand for one year and then to Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, staying there for the next 13 years.

The Holloways eventually returned to Bangkok where Jane attended Ruamrudee International School before leaving again for Australia and studying for her master’s degree in Sydney.

On her return to Thailand, Jane joined the Mae Fah Luang Foundation under Royal Patronage to work on the development project that took her to Afghanistan.

“We were working with 500 families in districts that cultivated opium poppies. If they were opium-free, what could the farmers do instead – that was the challenge,” says Jane. “The answer was to repopulate the area with sheep, which can be used for carpets and food, giving women roles to play in a patriarchal society, so there are all-round benefits.”

Despite the remoteness, the backwardness and the ever-present dangers of the still raging war, Jane was smitten by Afghanistan, “It was the most exciting place – I love the country. There’s something special about working in a war zone – the tanks, the intelligence, the people, the excitement. It’s tribal, dynamic and complicated.”

During this period, Jane also worked for UNHCR, initially in Thailand, profiling the refugee camps in Kanchanabrui and Mae Sot, home for some 140,000 displaced persons from Myanmar. Later she based herself in Kayah State, an area of Myanmar known for its ‘long necked’ tribespeople.

“My role was to identify what would be needed in terms of water and electricity if the refugees returned. I had to deal with government authorities, border police and representatives from seven different ethnic groups. As the only foreigner, I employed small cultural sensitivities liker wearing traditional Burmese clothing while negotiating with these officials.”

Today, Jane is busy with several new projects, including consulting for George Soros’s Open Society Foundation on its drug policy program, based in Bangkok. Another is advising on DragonFly360, a regional platform designed to mobilize society towards gender equality in Asia.

Looking back on her career, Jane says changing jobs so frequently enabled her to remain “relevant.”

“But now, for the first time, I feel I’m slowing down mentally. Today’s technology is complicated and I need to learn so much about social media.

“My motto is to help the most vulnerable in society, which I can do with facts and experience. I saw how elections are run and the political scramble for positions. As I said, I’m much more comfortable behind the scenes.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed