| After fleeing his Indonesian home after allegedly killing hundreds of people in a series of bombings, the man known as Hambali hid out in Thailand for several months before Thai Special Branch officers discovered his whereabouts and carried out his arrest. Special Correspondent Maxmilian Wechsler, who covered the case in 2003, recalls the events leading up to the capture of one of Asia’s most wanted men, including the key role of one courageous officer ON August 11, 2003, the man known as the ‘Bali Bomber,’ Indonesian Riduan Isamuddin, alias Hambali, was arrested in the city of Ayutthaya in central Thailand. The capture of the man believed to be the mastermind behind the 2002 Bali bombings which killed 202 people (including 88 Australians, 38 Indonesians, and people from more than 20 other nationalities) is regarded by many in the Thai law enforcement community as the most important case in the history of the Royal Thai Police. Hambali’s arrest was initiated from information developed by a high-ranking Special Branch (SB) officer who retired a few years ago. Although the officer prefers to remain anonymous to the public, his indispensable role in Hambali’s capture is readily acknowledged by high-level law enforcement and anti-terrorism officials in Thailand and around the world. |

The SB officer directed and supervised the entire investigation. He and his trusted team located Hambali and set the trap for him before officers from other Thai and foreign agencies were brought in. The SB officer personally arrested Hambali in Ayutthaya and was involved in the initial interrogation.

He was also part of the detail that sent him off on his journey out of Thailand three days after his arrest on a US plane flying out of Bangkok’s Don Mueang airport. Hambali was reportedly then held at clandestine CIA detention facilities for almost three years before being transferred on September 4, 2006 to Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, where he is still confined at the secretive Camp 7 maximum security facility.

Several Thai police officers contacted all agreed that the SB officer was extremely intelligent and capable, but also very modest. “He wasn’t after publicity, glory or monetary rewards. Everything he did was to serve his country, not only in the Hambali case but also many others involving national security,” one officer said.

Hambali was the military leader of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), an Indonesian terrorist organization linked to al-Qaeda that claimed responsibility for a number of deadly attacks in Southeast Asia, including the Bali nightclub bombing of October 12, 2002 that killed hundreds of people and injured many more.

Some media reports described him as Asia’s Osama bin Laden, and his photo was featured – rightly or wrongly – on the cover of the April, 2002 edition of TIME magazine. The headline on the cover read: “The Life and Times of Asia’s Terror Kingpin.” At that time Hambali was, after Osama, the most wanted man on the planet and the object of a global manhunt.

Phone call prompts ‘red alert’

The saga of Hambali’s arrest began on a hot afternoon in mid-March 2003, when the SB officer was going through some documents in his small office inside the RTP headquarters. His mobile phone rang. The caller was a Cambodian intelligence officer who had been following leads on JI members in Phnom Penh for a month. Cambodian police had arrested several Islamic teachers and extracted crucial information about Hambali and his Chinese-Malaysian wife, Noralwizah Lee Abdullah. “We just got information that Hambali and his wife have left for Thailand,” said the Cambodian officer.

“I immediately put my team on red alert,” said the SB officer. “My hunch was that Hambali was planning a big operation in Thailand. Bangkok was making preparations to host the October 2003 APEC summit and many world leaders were expected to attend, including (US President) George W. Bush.

“We set up a ‘war room’ and initiated a nationwide hunt for Hambali – later code-named ‘Operation Black Magic’ – that ended five months later when we captured Hambali.

“Everyone involved in the operation felt pressure to nab the man directly linked to bombings that had killed around 300 people,” said the SB officer.

Besides the Bali bombings (202 dead, more than 330 wounded), Hambali is also the alleged mastermind of the 2000 Christmas Eve bombings across Indonesia (19 dead, 47 wounded); the September 30, 2000 blast in Metro Manila (22 dead); and possibly the JW Marriott Hotel bombing in Jakarta on August 5, 2003 (12 dead, over 150 wounded).

Hambali is also believed to have organized a meeting with two of the 9/11 hijackers when they visited Kuala Lumpur in 2000, and he allegedly planned terrorist attacks in Singapore which were thwarted in 2001. The SB officer believes that the arrest of Hambali in Ayutthaya may have spared Bangkok a series of major terrorist attacks still in the planning stages.

He was also part of the detail that sent him off on his journey out of Thailand three days after his arrest on a US plane flying out of Bangkok’s Don Mueang airport. Hambali was reportedly then held at clandestine CIA detention facilities for almost three years before being transferred on September 4, 2006 to Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, where he is still confined at the secretive Camp 7 maximum security facility.

Several Thai police officers contacted all agreed that the SB officer was extremely intelligent and capable, but also very modest. “He wasn’t after publicity, glory or monetary rewards. Everything he did was to serve his country, not only in the Hambali case but also many others involving national security,” one officer said.

Hambali was the military leader of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), an Indonesian terrorist organization linked to al-Qaeda that claimed responsibility for a number of deadly attacks in Southeast Asia, including the Bali nightclub bombing of October 12, 2002 that killed hundreds of people and injured many more.

Some media reports described him as Asia’s Osama bin Laden, and his photo was featured – rightly or wrongly – on the cover of the April, 2002 edition of TIME magazine. The headline on the cover read: “The Life and Times of Asia’s Terror Kingpin.” At that time Hambali was, after Osama, the most wanted man on the planet and the object of a global manhunt.

Phone call prompts ‘red alert’

The saga of Hambali’s arrest began on a hot afternoon in mid-March 2003, when the SB officer was going through some documents in his small office inside the RTP headquarters. His mobile phone rang. The caller was a Cambodian intelligence officer who had been following leads on JI members in Phnom Penh for a month. Cambodian police had arrested several Islamic teachers and extracted crucial information about Hambali and his Chinese-Malaysian wife, Noralwizah Lee Abdullah. “We just got information that Hambali and his wife have left for Thailand,” said the Cambodian officer.

“I immediately put my team on red alert,” said the SB officer. “My hunch was that Hambali was planning a big operation in Thailand. Bangkok was making preparations to host the October 2003 APEC summit and many world leaders were expected to attend, including (US President) George W. Bush.

“We set up a ‘war room’ and initiated a nationwide hunt for Hambali – later code-named ‘Operation Black Magic’ – that ended five months later when we captured Hambali.

“Everyone involved in the operation felt pressure to nab the man directly linked to bombings that had killed around 300 people,” said the SB officer.

Besides the Bali bombings (202 dead, more than 330 wounded), Hambali is also the alleged mastermind of the 2000 Christmas Eve bombings across Indonesia (19 dead, 47 wounded); the September 30, 2000 blast in Metro Manila (22 dead); and possibly the JW Marriott Hotel bombing in Jakarta on August 5, 2003 (12 dead, over 150 wounded).

Hambali is also believed to have organized a meeting with two of the 9/11 hijackers when they visited Kuala Lumpur in 2000, and he allegedly planned terrorist attacks in Singapore which were thwarted in 2001. The SB officer believes that the arrest of Hambali in Ayutthaya may have spared Bangkok a series of major terrorist attacks still in the planning stages.

|

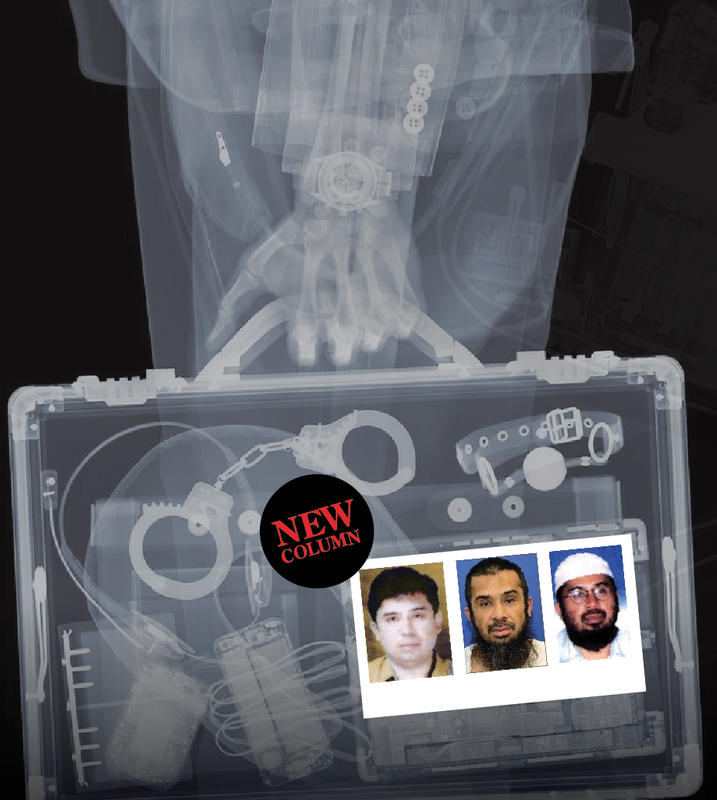

Following the tip from Phnom Penh, Thai officers began interrogating local and foreign Islamic extremists who had been detained in and around Bangkok. One of them confirmed that Hambali had entered Thailand from Cambodia. “The last foreigner we interrogated gave us the name of Hambali’s trusted aide. He also told us that Hambali was holding a Spanish passport bought from a pair of Pakistani forgers living in Thailand who were linked to a Russian-born criminal, who we arrested later,” said an officer in charge of the interrogation. “But none of them knew Hambali’s whereabouts.” Investigators were able to locate the aide, and in early August followed him to the immigration checkpoint at Mae Sai in Chiang Rai province. He then took a bus back to Bangkok. It was later learned that the aide was making a visa extension for Hambali. “We apprehended him at Ekkamai bus station when he started to run,” said the same officer. Police on hand seized two passports from the aide – his own and a Spanish passport being used by Hambali. This was not a fake as reported in the media; it was stolen from its owner, Daniel Suarez Naviera, whose photo was replaced with Hambali’s. Even better, the arresting officers found a key ring on the aide that held a room key and a name tag for the Boonyarak apartments in Ayutthaya. Police went to the apartment building and checked the list of tenants. A man they believed was Hambali was renting room 601on the 6th floor. The room had been rented by a Thai national. His aide rented another room on the same floor and shared it with another foreign male who was later arrested along with Hambali and his wife. The foreigner is believed to be a member of JI but his identity remains unknown. |

REPORT SAYS HAMBALI STILL A THREATAccording to a US Department of Defense report dated October 30, 2008, Hambali arrived at Guantanamo Bay in good health on September 4, 2006. An executive summary in the report makes the assessment that “if released without rehabilitation, close supervision, and means to successfully reintegrate into his society as a law abiding citizen, Hambali would “probably seek out prior associates and re-engage in hostilities and extremist support activities.” The report says Hambali appeared to be cooperating during interviews but may be withholding information. “Detainee appears to be truthful and forthcoming in relation to his prior history. Detainee has not attempted to provide a cover story and is consistent in his timeline. Detainee admits his membership to JI and his relationship to al-Qaeda. However, detainee refuses to divulge all information he has on particular operations and personnel. “Detainee has also justified his terrorist activities and downplays the severity of his actions,” says the 12-page report, which adds that Hambali’s “life and personal actions reflect his commitment to the most extreme Islamic ideology.” He was therefore determined to be both a high risk and of high intelligence value. |

“We wanted to catch Hambali without any bloodshed. Some people suggested that we break in but we didn’t know if he had explosives, grenades, or guns in his room, or if he would blow himself up and kill our men as well,” said the SB officer.

Finally the officer made a phone call to the highest official in Thai government, who instructed them to catch Hambali alive. It appeared that some people preferred to have him dead for some reason.

Shortly before 11pm on August 11, Thai police officers, Special Weapons Attack Team (SWAT), and personnel from the Armed Forces Security Centre (AFSC) and National Intelligence Agency (NIA) were positioned in and around the Boonyarak apartments. On directions from police, a telephone operator called Hambali to come downstairs to discuss a matter regarding his phone line.

Ever cautious, Hambali left the lift on the second floor and began walking downstairs. He was intercepted by the SB officer who recognized him immediately and told him that he was under arrest. Still standing on the stairs and looking down on the SB officer, Hambali managed to kick him in the stomach before the alleged terrorist was quickly wrestled to the ground by several policemen and other security people.

His captors recovered two fully-loaded .380 mm calibre Soviet-made Makarov pistols from his trouser pockets. Hambali reportedly obtained the guns in Cambodia. He was wearing jeans and T-shirt, a baseball cap and sunglasses.

Shortly afterwards, SWAT team officers armed with HK MP5 machine guns broke into room 601 and arrested Hambali’s wife and the foreign JI man. At the same time they also stormed the other room but found no one inside. Both rooms were then thoroughly searched and sealed.

The SB officer displayed considerable bravery in confronting Hambali. Happily he was not seriously hurt. And luckily, Hambali didn’t have the time to draw his two guns…

Ominous evidence

In Hambali’s room police found a manual describing how to assemble a bomb, a large amount of money in Thai baht and various documents, but no explosive materials or bombs. Information in the seized documents led investigators to believe Hambali planned to carry out a series of bomb attacks during the APEC summit.

Among the targets were the US and British embassies in Bangkok, nightclubs in Phuket and Pattaya, and the check-in counter of El Al Israeli Airlines at Don Mueang airport. Hambali was also apparently planning an attack on an Israeli restaurant in the Khao San Road area.

The SB officer said that Hambali, who was interrogated shortly after his arrest, gave them no useful information during the interrogation, such as why he had come here and what he had planned. “He was very clever and convincing talker. After talking to him for several hours, one might be even convinced that the cause of Islamic militancy is right.”

Thai intelligence officers stated that Hambali was in Thailand as early as September 2002 before he crossed into Cambodia. There, he first stayed in an apartment near the railway station in Phnom Penh and later moved to a guesthouse by Boeng Kak Lake. The owner told Cambodian police that the man he rented to was using the name of “Mizi” and told him he was a businessman. He smoked Marlboro cigarettes and drank Coca Cola. While in his room he listened to BBC radio and read English-language magazines. Cambodian authorities were poised to arrest Hambali when he suddenly disappeared.

Hambali told Thai interrogators that after arriving back in Thailand he lived in the Huamark area of Bangkok before moving to Ayutthaya. “He said he was very upset with the debauchery of Thai Muslims he met in Huamark. Seeing young couples shacking up who behaved like Westerners, drank alcohol and always asked him for money, he said he couldn’t live there anymore. A friend advised him to go to Ayutthaya because many good Muslims lived there and he would be safe.”

Hambali and his wife moved to the Boonyarak apartment in Ayutthaya about three weeks before the trap was sprung. The arrest caused a commotion in the normally quiet neighbourhood. Residents were astounded that the man they had seen walking about with his wife and engaged in normal, everyday activities was the object of a global manhunt.

Two motorcycle taxi drivers who easily recognized the couple from photos gave a glimpse of Hambali’s final days of freedom. “He and his wife were always together and casually dressed, like Westerners,” said one. “They shopped at the 7-Eleven from time to time. They usually left the apartment around 9pm and walked across the street to a food market. I never saw them during the daytime.”

Another motorcycle taxi driver who worked nights said he saw Hambali leaving the apartment alone around 11pm three or four times. “He would wait on the corner for 10-15 minutes before crossing the main road to the gas station, where a sedan and two modified pick-ups were waiting. Hambali would get inside the sedan and appeared to engage the occupants in a long discussion. He was never in the sedan when it drove off.”

The driver added that he sometimes saw Arab-looking men wearing white robes and white skull-caps outside the vehicles. “The cars sometimes took fuel and the passengers went to the toilet.”

One foreigner who researched Hambali’s case said that these meetings have hallmarks of an important person talking to him. Three cars could indicate a presence of a security detail. There are still some unanswered questions about his association with certain foreigners before he was arrested.

Hambali was flown out of Thailand on a special US jet three days after his arrest. A convoy of cars took him to a remote section of Don Muang airport at night under tight security at night. All the lights were switched off in the section and it was guarded by heavily-armed commandos.

“Hambali was walking alongside Thai officers and taken to the US plane inside a hangar where several foreign agents were waiting,” said one officer, adding that Hambali’s wife was deported to Malaysia and detained there by the authorities. It is suspected that the aide and another foreign accomplice also ended up at Guantanamo Bay, but even after 13 years this can’t be confirmed.

NO WELCOME HOME

Soon Hambali will ‘celebrate’ the thirteen anniversary of his capture in Ayutthaya and tenth year at Guantanamo, although he has never been formally charged with a crime by the Americans.

In the past his detention has been the source of tension between Indonesia and the US, the former wanting him to face trial in his native country. On March 8 this year, Luhut Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, said that his government does not want Hambali back. He added that Indonesian officials are “discussing all necessary steps” to ensure that he stays in US custody if Guantanamo is closed.

According to a terrorism expert, the Indonesian government fears that if Hambali is transferred to an Indonesian prison his presence would give a boost to militants inside the prison and in the country as a whole. The expert cited cases where jailing terrorists has led to radicalization of other inmates, and noted that detained extremists maintain links with outside terrorist networks.

In the past his detention has been the source of tension between Indonesia and the US, the former wanting him to face trial in his native country. On March 8 this year, Luhut Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, said that his government does not want Hambali back. He added that Indonesian officials are “discussing all necessary steps” to ensure that he stays in US custody if Guantanamo is closed.

According to a terrorism expert, the Indonesian government fears that if Hambali is transferred to an Indonesian prison his presence would give a boost to militants inside the prison and in the country as a whole. The expert cited cases where jailing terrorists has led to radicalization of other inmates, and noted that detained extremists maintain links with outside terrorist networks.

Thai heroics go unsung

The news of Hambali’s arrest apparently reached President Bush while he was aboard Air Force One on a flight from Texas to California on August 14, 2003. A White House spokesman called it an “important victory in the war on terrorism” and a “significant blow to al-Qaeda.”

In a speech to US Marines in San Diego later the same day, President Bush said: “Hambali is one of the world’s most lethal terrorists, suspected of planning major terrorist operations. He is no longer a problem for those of us who love freedom.” Australian Prime Minister John Howard also expressed pleasure upon hearing of the capture of the man he called the “ultimate mastermind” of the Bali bombings.

Despite the great importance placed by world leaders and the media on the arrest of Hambali, the Thai officers who made it a reality received scant credit or respect. They also saw little of the US$10 million reward paid by the US government. “Most of the money was distributed among officials who had nothing to do with the case,” said a senior Thai police officer.

He also said that most media reports on the case were incorrect, for two reasons. “First, we had to conceal some information to protect our sources; second, people from a certain organization wanted all the credit, as if they had done everything.”

The SB officer in charge of the case said: “We used all the people we could trust and all the equipment at our disposal. Some agencies paid little attention to our requests for assistance. We were joined later by personnel from the AFSC and the NIA, with support from a Western intelligence agency, but without the tip-off from Cambodia and the hard work done by my people, Thailand may well have seen a series of devastating bomb attacks.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed