Thai police often come in for massive criticism, but investigate a bit deeper and it turns out they work long hours doing a difficult job in dangerous circumstances for scant reward. All they want is a little appreciation from the public

By Maxmilian Wechsler

| SCARCELY a day goes by that doesn’t see allegations of corruption, laziness, incompetence or other criticism levelled by the media at the Royal Thai Police (RTP), especially in local and international English-language outlets. While Thai-language newspapers, television, magazines and websites are somewhat more balanced, the overall negative coverage contributes to a prevailing opinion that Thai police have a soft job and are mainly occupied with feathering their own nests. But anyone who takes the time to sit down and talk to some of them soon realizes this is unfair. No other government agency has to contend with anything like the barrage of negative press that descends on the police on an almost daily basis. We are constantly reminded of bribe-taking by police, but it’s worth remembering that for the average cop this amounts to small sums from motorists in lieu of a traffic ticket. And often it is the motorists who are most eager to make a cash deal on the spot to avoid the inconvenience of having their driving license confiscated and going to the police station to pay a fine. |

Contrast this to corruption in the private sector. Graft perpetrated by big corporations is believed to siphon off hundreds of millions of baht from the country’s GDP. We hear precious little in the media about so-called white collar crimes like insider trading, fraud, embezzlement and tax evasion. Corruption in sports on a tremendous scale is also overlooked. Reports of match fixing, doping, gambling and other illegal activities plague sports all around the world, but in general the athletes remain admired and emulated. While some criticism of the police is certainly valid, there is little appreciation of the risks they take and the long, hard hours they work.

A police officer’s job places him or her in the center of surroundings and situations that most people would do anything to avoid. Whenever there is a robbery, assault, shooting, bombing or other violent crime people always look first to the police to find the perpetrators and restore order. They are also on the scene of traffic accidents and disasters such as fires and floods, and they are called on to settle family disputes and even to remove snakes from residences.

But stories that look deeply into the lives and working conditions of ordinary police officers rarely appear in the media unless it is to report on a tragic event like the alleged suicide of Police Captain Tawee Meunrak. The policeman attached to Thung Song Hong police station is believed to have shot himself on January 29 because of work-related stress. Before people take aim from the comfort and safety of their homes at the men and women patrolling Thailand’s meanest streets, they should pause to consider whether their criticism is really warranted.

Police live with the knowledge that every time they put on their uniforms they may be killed or injured in the act of chasing or arresting criminals. Adding to the pressure are rising crime rates brought on by tough economic times which also make the perpetrators more desperate. What’s more, in many cases criminals are well armed and willing to resist and fight the police. One former senior police officer attached to the Pathum Thani provincial police said that these days drug traffickers and other hard-core criminals often bring out not only handguns but assault rifles in their confrontations with police.

Contacts with law-abiding citizens can take a toll as well. Police are on the scene at the thousands of grisly traffic accidents that occur each year in Thailand. They draw up reports and sometimes take photos of injured and deceased motorists, motorcyclists and pedestrians. They also take charge of the grim business of investigating suicides and overseeing the collection of the bodies.

At the end of a day filled with such activities, they still have to attend to paperwork and other assorted duties. This means they almost invariably work long hours, and without overtime. There is no increase in pay rate for working nights, weekends or holidays, and a police officer must be prepared to answer the call of duty at any time, 24/7. How many factory and office workers, not to mention company executives or journalists, would take a job like that?

A police officer’s job places him or her in the center of surroundings and situations that most people would do anything to avoid. Whenever there is a robbery, assault, shooting, bombing or other violent crime people always look first to the police to find the perpetrators and restore order. They are also on the scene of traffic accidents and disasters such as fires and floods, and they are called on to settle family disputes and even to remove snakes from residences.

But stories that look deeply into the lives and working conditions of ordinary police officers rarely appear in the media unless it is to report on a tragic event like the alleged suicide of Police Captain Tawee Meunrak. The policeman attached to Thung Song Hong police station is believed to have shot himself on January 29 because of work-related stress. Before people take aim from the comfort and safety of their homes at the men and women patrolling Thailand’s meanest streets, they should pause to consider whether their criticism is really warranted.

Police live with the knowledge that every time they put on their uniforms they may be killed or injured in the act of chasing or arresting criminals. Adding to the pressure are rising crime rates brought on by tough economic times which also make the perpetrators more desperate. What’s more, in many cases criminals are well armed and willing to resist and fight the police. One former senior police officer attached to the Pathum Thani provincial police said that these days drug traffickers and other hard-core criminals often bring out not only handguns but assault rifles in their confrontations with police.

Contacts with law-abiding citizens can take a toll as well. Police are on the scene at the thousands of grisly traffic accidents that occur each year in Thailand. They draw up reports and sometimes take photos of injured and deceased motorists, motorcyclists and pedestrians. They also take charge of the grim business of investigating suicides and overseeing the collection of the bodies.

At the end of a day filled with such activities, they still have to attend to paperwork and other assorted duties. This means they almost invariably work long hours, and without overtime. There is no increase in pay rate for working nights, weekends or holidays, and a police officer must be prepared to answer the call of duty at any time, 24/7. How many factory and office workers, not to mention company executives or journalists, would take a job like that?

| The view from Bang Phli police station It takes 30 to 40 minutes to drive from the center of Bangkok to the Bang Phli police station in Samut Prakan province, where Police Colonel Dr Pullop Aramhla, the station's Superintendent, gave an extensive and candid interview. He also allowed an interview with rank-and-file police and granted unlimited access to a modern, well-equipped police station, which has signs in both Thai and English and is divided into five sections: Investigation, Inquiry, Patrol, Traffic, and Administration. Speaking good English, Pol Col Pullop was extremely frank during a long conversation in his modest second floor office. “We cover 150 square kilometers with about 200,000 people, including about 60,000 migrant workers from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos who are employed at the many factories in the area,” said the superintendent, who has a doctorate in Philosophy. “The station has 140 policemen and 10 policewomen, and this is not enough. We are understaffed, and therefore everyone assigned here, including me, has to work hard and long hours to fulfill our responsibilities as expected by the public and the RTP. I have been here for 16 months and before that I was attached to the Samut Prakan Provincial Police Division headquarters for three years. Sixteen months is not long enough to accomplish what I want to do, which is to educate the law enforcement professionals here and bring crime under control in the district. |

“If there’s nothing too urgent I go to bed at 12.30am and wake up at 5.30am. I have almost no free time. Every morning I monitor traffic, which is very heavy in the early morning hours because there are so many trucks on the roads. At around 10am I have to look over and sign many documents. At 1pm I check on various places like banks. We don’t station police in banks because we don’t have enough staff. A big part of the job is breaking up brawls. First it’s students, starting around 4pm, and later, after 7pm, mostly factory workers. In the nighttime we are called to a lot of traffic accidents mainly involving motorcycles. There’s always something happening.

“Around three times a week I attend meetings at Samut Prakan Police Division headquarters. There are many meeting at this station also, for example on action plans to apprehend suspects.

"As superintendent I am responsible for every police officer here. My mobile is on 24/7. Sometimes I get a call at 2am to come to the scene of a deadly accident. It is non-stop work, and not just for me. Anyone who puts on an RTP uniform has a difficult and dangerous job. Unfortunately, all too often criminals make a choice to take out a gun and start shooting to try and avoid arrest.

“We don’t have set working hours like employees of a private company. We can’t say ‘it’s 4.30pm and I’m going home.’ Our hours depend on the number of cases and overall security situation in the district. And since there are always so many cases coming at us the reality is that we are subject to be called to report for duty at any time, with no extra pay, for weekends or public holidays,” said Pol Col Pullop, adding that police pay the same income tax rate as people who work in the private sector.

“There are three eight-hour shifts with patrols that must each be staffed by 50 police. Policewomen are mostly attached to the administrative section as there are a great many documents to process every day. But sometimes they accompany the men on patrols. In some investigations we use policewomen for undercover work because they are better suited in certain situations. If there’s a big crime or incident in our area we have to call everybody out, men and women,” said Pol Col Pullop.

“Around three times a week I attend meetings at Samut Prakan Police Division headquarters. There are many meeting at this station also, for example on action plans to apprehend suspects.

"As superintendent I am responsible for every police officer here. My mobile is on 24/7. Sometimes I get a call at 2am to come to the scene of a deadly accident. It is non-stop work, and not just for me. Anyone who puts on an RTP uniform has a difficult and dangerous job. Unfortunately, all too often criminals make a choice to take out a gun and start shooting to try and avoid arrest.

“We don’t have set working hours like employees of a private company. We can’t say ‘it’s 4.30pm and I’m going home.’ Our hours depend on the number of cases and overall security situation in the district. And since there are always so many cases coming at us the reality is that we are subject to be called to report for duty at any time, with no extra pay, for weekends or public holidays,” said Pol Col Pullop, adding that police pay the same income tax rate as people who work in the private sector.

“There are three eight-hour shifts with patrols that must each be staffed by 50 police. Policewomen are mostly attached to the administrative section as there are a great many documents to process every day. But sometimes they accompany the men on patrols. In some investigations we use policewomen for undercover work because they are better suited in certain situations. If there’s a big crime or incident in our area we have to call everybody out, men and women,” said Pol Col Pullop.

Rewards don’t match the risks

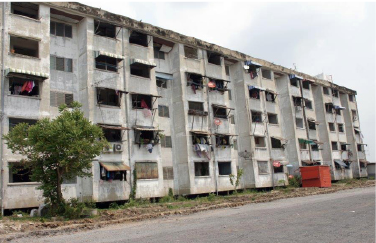

The government provides apartments for police officers and their families, but only around 10 percent are able to live in the building adjacent to the station. There are other rent-free residences within a 10 kilometer-radius of the station – the reach of police radio transmitters. The rent is free at these residences except for electricity and water. The government apartments consist of one or two rooms and are allocated according to rank and whether family members are in residence. Those who chose to stay in other accommodations must pay the cost themselves.

Most rent-free police flats located close to police stations are mostly decades old and quite run down, but some are relatively new. Overall, though, they are from ideal; the rooms are small and basic while the premises can be crowded and noisy.

Police must buy their own motorcycles if they are needed for the job. Those who live away from the station must have some form of private transportation so they can respond quickly in an emergency. The cost of the basic equipment like uniforms, decorations, handguns, transceivers, handcuffs, hats and belts also comes out of their own pockets. A good handgun is expensive and costs around 70,000 baht. Some police don’t have a gun because they just can’t afford it. Handguns can be purchased by installment through the police cooperative, however.

“Police and their family members are entitled to a free medical care, medicine and whatever treatment is necessary but only in government hospitals,” said Pol Col Pullop.

The superintendent explained that if someone commits a major crime in his district and runs away to Chiang Mai, for example, police stationed at Bang Phli are responsible for apprehending the criminal. “We have to follow them, and this could mean contacting relatives wherever they may live. The government gives us some budget for this type of circumstance which includes transportation, accommodation and food, but often it is not enough. In such cases we have to use money budgeted for essential purposes in order to succeed with the investigation and arrest the suspect.

“The government’s budget allocation for fuel for our 20 police cars and motorcycles is often not enough either. Usually the budget for petrol runs out sometimes after the 20th of the month, so we have to find the money elsewhere. Often I pay from my own pocket.”

Operations

Pol Col Pullop showed me around Bang Phli station’s modern Traffic Control Center. “Dispatchers are on duty around the clock and upon receiving a call they radio to one of our patrol teams, who promptly proceed to the scene. The control center is equipped with 16 colour monitors that receive feeds from strategically placed CCTV cameras and show how traffic is flowing in the area. Everything is recorded. The center also has nine large television screens mounted on the wall and tuned to different Thai TV news channels.”

He then explained the procedure for patrols sent to traffic accidents: “After arriving at the scene of an accident, the patrolmen take photos of the crash site, draw a map of the scene and talk to witnesses. The same police team must make a report back at the station and contact the families of victims. Then they go to the hospital to see the victims and help make identifications if there are deaths. In some cases vehicles are impounded for forensic examination. A lot of documents have to be written up and the patrolmen are assisted in this by our administrative personnel. Sometimes the case goes to the prosecutor and to court and the police who took the call must also appear in court.

“The number of cases that must be investigated differs from station to station, of course,” said the superintendent. “In a relatively quiet district it might be 500 per year, while a district in Pattaya might see 5,000. We must respond to about 2,000 cases per year and around five serious cases every day. Fifty percent of all cases we handle involve narcotics, especially methamphetamine tablets (yaba) and crystal methamphetamine (‘ice’). The second most common problem is fighting. These involve mainly migrant workers from neighbouring countries who have had too much to drink. These situations are lethal sometimes.

“Most nights we receive two, three or even more calls about migrant workers causing a disturbance to our emergency 191 and Bang Phli police station number (02 337 3377) with requests for assistance. There’s no problem with communication in these situations. Most migrant workers can speak some English and so can we. We usually have enough manpower to attend to all emergencies but sometimes they pile up and people who need help have to wait,” said Pol Col Pullop, adding that the third most common problem is theft and the fourth is serious traffic accidents.

More police perspective

One of the station’s young police officers explained that after graduating from the Royal Police Cadet Academy he was attached to another police station in Bangkok before being transferred to Bang Phli about a year ago. Asked why he joined the RTP, he answered: “I want to serve my people and my country.” He insisted that he won’t accept bribes from anyone, no matter how much money is offered, and he follows the law no matter how big or influential any suspect thinks they are. “If someone breaks the law I will arrest them, period.”

The young officer said that his uniform and accessories cost him altogether about 4,000 baht. “The silver stars on my shoulder cost me 250 baht each, and I have four. Guns are expensive and some policemen don’t feel they can afford to buy a good one, but my philosophy is that this is a dangerous occupation and a reliable handgun is a necessity.

However, those attached to the administrative section don’t necessarily need a gun.”

He echoed his superior’s comments about problems with migrant workers adding to their workload. “We have tens of thousands of workers from neighbouring countries, especially Myanmar and Cambodia, working in factories in and around Bang Phli. They are willing to work for 300 baht a day or less and some are undocumented. These enter Thailand illegally. Some are smuggled through Mae Sot or Kanchanaburi. Some are registered to work in a certain job but they do some other kind of work. This is also illegal.

“When migrant workers fight we are called to break them up and sometimes we make arrests, and sometimes when we arrive there are dead bodies that must be taken care of. In my experience not many migrant workers take narcotics, maybe because they can’t afford it. They prefer to drink alcohol.”

Bang Phli has cells for prisoners who can be kept there for up to 48 hours. “After that we send the suspect to the court in Samut Prakan. In a big case, the court can order detention up to 84 days before a trial. We have to bring suspects to the court whenever their cases are being considered. We have a prison car with a police driver and guards who accompany suspects to the criminal court, or juvenile court if the suspect is under 18 years.”

One policeman asked what foreigners in Thailand think about the police. When told of the general perception, none of the officers seemed at all surprised. A police colonel in charge of investigations asked for this message to be passed on: “All policemen and policewomen assigned to Bang Phli police station would like to tell foreigners and the Thai public that we are working very hard to ensure safety for the public. I am sure that this is the case all over Thailand.

“Often when we are sleeping or trying to relax a call comes in and we have to go to work.”

His emotional declaration and the enthusiastic approval given by his colleagues were unexpected. The camaraderie and esprit de corps among them are clearly very strong.

One young policeman remarked on an apparent paradox: “It’s funny, you know. The public always criticizes us, the job is dangerous, the hours are long and the rewards are small, but whenever there’s a recruiting program there are always more than 10,000 applicants wanting to join us.’

The BigChilli wishes to thank Police Colonel Dr Pullop Aramhla, Superintendent of the Bang Phli police station, and several officers under his command for providing insight into their daily lives.

The government provides apartments for police officers and their families, but only around 10 percent are able to live in the building adjacent to the station. There are other rent-free residences within a 10 kilometer-radius of the station – the reach of police radio transmitters. The rent is free at these residences except for electricity and water. The government apartments consist of one or two rooms and are allocated according to rank and whether family members are in residence. Those who chose to stay in other accommodations must pay the cost themselves.

Most rent-free police flats located close to police stations are mostly decades old and quite run down, but some are relatively new. Overall, though, they are from ideal; the rooms are small and basic while the premises can be crowded and noisy.

Police must buy their own motorcycles if they are needed for the job. Those who live away from the station must have some form of private transportation so they can respond quickly in an emergency. The cost of the basic equipment like uniforms, decorations, handguns, transceivers, handcuffs, hats and belts also comes out of their own pockets. A good handgun is expensive and costs around 70,000 baht. Some police don’t have a gun because they just can’t afford it. Handguns can be purchased by installment through the police cooperative, however.

“Police and their family members are entitled to a free medical care, medicine and whatever treatment is necessary but only in government hospitals,” said Pol Col Pullop.

The superintendent explained that if someone commits a major crime in his district and runs away to Chiang Mai, for example, police stationed at Bang Phli are responsible for apprehending the criminal. “We have to follow them, and this could mean contacting relatives wherever they may live. The government gives us some budget for this type of circumstance which includes transportation, accommodation and food, but often it is not enough. In such cases we have to use money budgeted for essential purposes in order to succeed with the investigation and arrest the suspect.

“The government’s budget allocation for fuel for our 20 police cars and motorcycles is often not enough either. Usually the budget for petrol runs out sometimes after the 20th of the month, so we have to find the money elsewhere. Often I pay from my own pocket.”

Operations

Pol Col Pullop showed me around Bang Phli station’s modern Traffic Control Center. “Dispatchers are on duty around the clock and upon receiving a call they radio to one of our patrol teams, who promptly proceed to the scene. The control center is equipped with 16 colour monitors that receive feeds from strategically placed CCTV cameras and show how traffic is flowing in the area. Everything is recorded. The center also has nine large television screens mounted on the wall and tuned to different Thai TV news channels.”

He then explained the procedure for patrols sent to traffic accidents: “After arriving at the scene of an accident, the patrolmen take photos of the crash site, draw a map of the scene and talk to witnesses. The same police team must make a report back at the station and contact the families of victims. Then they go to the hospital to see the victims and help make identifications if there are deaths. In some cases vehicles are impounded for forensic examination. A lot of documents have to be written up and the patrolmen are assisted in this by our administrative personnel. Sometimes the case goes to the prosecutor and to court and the police who took the call must also appear in court.

“The number of cases that must be investigated differs from station to station, of course,” said the superintendent. “In a relatively quiet district it might be 500 per year, while a district in Pattaya might see 5,000. We must respond to about 2,000 cases per year and around five serious cases every day. Fifty percent of all cases we handle involve narcotics, especially methamphetamine tablets (yaba) and crystal methamphetamine (‘ice’). The second most common problem is fighting. These involve mainly migrant workers from neighbouring countries who have had too much to drink. These situations are lethal sometimes.

“Most nights we receive two, three or even more calls about migrant workers causing a disturbance to our emergency 191 and Bang Phli police station number (02 337 3377) with requests for assistance. There’s no problem with communication in these situations. Most migrant workers can speak some English and so can we. We usually have enough manpower to attend to all emergencies but sometimes they pile up and people who need help have to wait,” said Pol Col Pullop, adding that the third most common problem is theft and the fourth is serious traffic accidents.

More police perspective

One of the station’s young police officers explained that after graduating from the Royal Police Cadet Academy he was attached to another police station in Bangkok before being transferred to Bang Phli about a year ago. Asked why he joined the RTP, he answered: “I want to serve my people and my country.” He insisted that he won’t accept bribes from anyone, no matter how much money is offered, and he follows the law no matter how big or influential any suspect thinks they are. “If someone breaks the law I will arrest them, period.”

The young officer said that his uniform and accessories cost him altogether about 4,000 baht. “The silver stars on my shoulder cost me 250 baht each, and I have four. Guns are expensive and some policemen don’t feel they can afford to buy a good one, but my philosophy is that this is a dangerous occupation and a reliable handgun is a necessity.

However, those attached to the administrative section don’t necessarily need a gun.”

He echoed his superior’s comments about problems with migrant workers adding to their workload. “We have tens of thousands of workers from neighbouring countries, especially Myanmar and Cambodia, working in factories in and around Bang Phli. They are willing to work for 300 baht a day or less and some are undocumented. These enter Thailand illegally. Some are smuggled through Mae Sot or Kanchanaburi. Some are registered to work in a certain job but they do some other kind of work. This is also illegal.

“When migrant workers fight we are called to break them up and sometimes we make arrests, and sometimes when we arrive there are dead bodies that must be taken care of. In my experience not many migrant workers take narcotics, maybe because they can’t afford it. They prefer to drink alcohol.”

Bang Phli has cells for prisoners who can be kept there for up to 48 hours. “After that we send the suspect to the court in Samut Prakan. In a big case, the court can order detention up to 84 days before a trial. We have to bring suspects to the court whenever their cases are being considered. We have a prison car with a police driver and guards who accompany suspects to the criminal court, or juvenile court if the suspect is under 18 years.”

One policeman asked what foreigners in Thailand think about the police. When told of the general perception, none of the officers seemed at all surprised. A police colonel in charge of investigations asked for this message to be passed on: “All policemen and policewomen assigned to Bang Phli police station would like to tell foreigners and the Thai public that we are working very hard to ensure safety for the public. I am sure that this is the case all over Thailand.

“Often when we are sleeping or trying to relax a call comes in and we have to go to work.”

His emotional declaration and the enthusiastic approval given by his colleagues were unexpected. The camaraderie and esprit de corps among them are clearly very strong.

One young policeman remarked on an apparent paradox: “It’s funny, you know. The public always criticizes us, the job is dangerous, the hours are long and the rewards are small, but whenever there’s a recruiting program there are always more than 10,000 applicants wanting to join us.’

The BigChilli wishes to thank Police Colonel Dr Pullop Aramhla, Superintendent of the Bang Phli police station, and several officers under his command for providing insight into their daily lives.

RTP in focus

THE Royal Thai Police (RTP) has authority in all of Thailand’s 76 provinces, which are divided into nine regions. In all, there are roughly 230,000 police men and women under the RTP throughout Thailand, based at 1,465 police stations including almost 100 in the Bangkok Metropolitan area.

Bang Phli police station has jurisdiction over a combined residential and industrial area. It is one of 14 under the Samut Prakan Provincial Police Division. Together with four neighbouring provinces in Greater Bangkok – Nakhon Pathom, Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani and Samut Sakhon – it forms Provincial Police Region 1, whose headquarters are on Wiphawadi Rangsit Road.

THE Royal Thai Police (RTP) has authority in all of Thailand’s 76 provinces, which are divided into nine regions. In all, there are roughly 230,000 police men and women under the RTP throughout Thailand, based at 1,465 police stations including almost 100 in the Bangkok Metropolitan area.

Bang Phli police station has jurisdiction over a combined residential and industrial area. It is one of 14 under the Samut Prakan Provincial Police Division. Together with four neighbouring provinces in Greater Bangkok – Nakhon Pathom, Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani and Samut Sakhon – it forms Provincial Police Region 1, whose headquarters are on Wiphawadi Rangsit Road.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed