Lifestyle

The world of the ‘farangs’ of the day in Bangkok revolved around activities loosely bounded by New Road from Sathorn to Siphya Roads, north to Petchburi Road, east to Rajadamri (New Petchburi Road did not exist then) down to Ploenchit, east again on Sukhumvit to about Soi Asoke 19, which was the end of civilization and the beginning of the boondocks all the way to the Cambodian border (in 1949, Sukhumvit Road was only paved to Soi 20; after that it was dirt and gravel), south down Wireless Road, east again on Rama IV Road, into the port in Klong Toey.

Most of these roads were tree-lined with enormous rain trees and were bordered by ‘klongs,’ most of which were navigable and connected to the Chao Phya River – the Siamese Mother of Waters. These had been the avenues of commerce in the old days. Eventually, all were covered over or filled in to expand the surface roads to handle the increase of vehicular traffic.

The ‘sois’ leading off of them were often not paved, just compacted dirt, and in the rainy season very muddy. Then west down Rama IV and New Road to Chinatown, down Yawarat Road, Sampeng Alley, Nakorn Kasem (the Thieves Market where you bought back what was stolen by the ‘kamoeys’ the night before) to the Rattanakosin Island/Rajadamnern Avenue area with the government offices, the courts, two universities and the Grand Palace, the Temple on the Golden Mount and the Dusit Zoo. And, of course, on Rajadamnern Avenue with the Rattanakosin (the ‘Rat’) and Majestic Hotels and the infamous Cathay Night Club.

The transnational corporations of the day considered Bangkok to be a hardship post with entitlements to extra allowances – no resident dared to disillusion them. Social life for Americans, Europeans and cultivated foreign-educated Thais centered pretty much on the Royal Bangkok Sports Club with its horse racing, swimming pool, tennis, squash and badminton courts, field sports, golf, card-reading and billiard rooms (for men only) and parties, parties, parties, often in costume. For many years it had been the only place in the city where you could take a hot shower!

The world of the ‘farangs’ of the day in Bangkok revolved around activities loosely bounded by New Road from Sathorn to Siphya Roads, north to Petchburi Road, east to Rajadamri (New Petchburi Road did not exist then) down to Ploenchit, east again on Sukhumvit to about Soi Asoke 19, which was the end of civilization and the beginning of the boondocks all the way to the Cambodian border (in 1949, Sukhumvit Road was only paved to Soi 20; after that it was dirt and gravel), south down Wireless Road, east again on Rama IV Road, into the port in Klong Toey.

Most of these roads were tree-lined with enormous rain trees and were bordered by ‘klongs,’ most of which were navigable and connected to the Chao Phya River – the Siamese Mother of Waters. These had been the avenues of commerce in the old days. Eventually, all were covered over or filled in to expand the surface roads to handle the increase of vehicular traffic.

The ‘sois’ leading off of them were often not paved, just compacted dirt, and in the rainy season very muddy. Then west down Rama IV and New Road to Chinatown, down Yawarat Road, Sampeng Alley, Nakorn Kasem (the Thieves Market where you bought back what was stolen by the ‘kamoeys’ the night before) to the Rattanakosin Island/Rajadamnern Avenue area with the government offices, the courts, two universities and the Grand Palace, the Temple on the Golden Mount and the Dusit Zoo. And, of course, on Rajadamnern Avenue with the Rattanakosin (the ‘Rat’) and Majestic Hotels and the infamous Cathay Night Club.

The transnational corporations of the day considered Bangkok to be a hardship post with entitlements to extra allowances – no resident dared to disillusion them. Social life for Americans, Europeans and cultivated foreign-educated Thais centered pretty much on the Royal Bangkok Sports Club with its horse racing, swimming pool, tennis, squash and badminton courts, field sports, golf, card-reading and billiard rooms (for men only) and parties, parties, parties, often in costume. For many years it had been the only place in the city where you could take a hot shower!

"These were the days before air-conditioning had become commonplace in Bangkok. There were three seasons – cool, rainy and hot – otherwise designated as ‘hot, very hot and damn it’s hot!"

| The British and Commonwealth citizens and subjects also enjoyed the British Club, still functioning at its original site between Suriwongse and Silom Roads, home for the St. George, St. Andrews, St. David and St. Patrick Societies. The Bangkok Riding and Polo Club catered to the equestrian set, but horseback-riding for pleasure faded as other forms of entertainment and sports vied for the time of its members. The Royal Turf Club was devoted solely to horse racing and rearing. The shipping industry supported the quaint Mariners Club adjacent to the entrance to the Port of Bangkok, now gone. Remember that these were the days before air-conditioning had become commonplace in Bangkok. There were three seasons – cool, rainy and hot – otherwise designated as ‘hot, very hot and damn it’s hot!’ Sitting at your desk, sweat would roll down your arms, back and chest. Everyone had ceiling fans and sometimes heavy rotating floor fans. Aside from a hospital or two, perhaps some diplomatic offices and some movie theaters, the first air-conditioned eatery was the Chez Eve Restaurant, owned by a couple of the Sea Supply men. Decent steaks – but only buffalo meat – no corn-fed American beef was to be seen for many years until during the Vietnam War when it “fell off the back of the truck” (along with booze and cigarettes) on the way to the American military commissary. And no peanut butter and no ice cream – you made your own at home. Well, until Lou Cykman’s ‘Dairy Bell’ ice cream appeared on the scene, there was one place, Chom Suey Hong on New Road, between the Chez Eve Club just off the foot of Suriwongse Road and my father’s law office above the Bank of America, where you could buy ice cream treats. At night time it converted into a rancorous night club, with beauteous partners for dancing, of course. You shopped for foodstuffs at the Silom Store or the Tong Who Store, both on Silom Road. Lots of canned goods, but forget frozen foods. Fresh cheeses and fresh dairy products were difficult to find in Thailand. Fresh fruits, veggies and meats were bought daily at the local fresh food markets. |

Fresh eggs were available principally at Robinson’s Piano Store on Suriwongse Road – as piano sales were infrequent, the owners' sideline was raising chickens. Foods not put in the refrigerator (yes, we had them then), were kept in screened cabinets on stilts with each leg in a bowl of water. This served as a moat to prevent ants from climbing up the legs and eating everything. Cockroaches swam or flew across. Pump action flit guns kept the insects at bay – some people as well!

Thai, British, French, Dutch, Japanese and Chinese banks and the Bank of America operated efficiently, so funds were available for lending, if supported by land, personal guarantees and compradors. The Baht, or Tical as it was formerly called, exchange rate for the U.S. Dollar was rock steady for many years at 20:1. “A Tical is a nickel” was a favorite saying.

Thai, British, French, Dutch, Japanese and Chinese banks and the Bank of America operated efficiently, so funds were available for lending, if supported by land, personal guarantees and compradors. The Baht, or Tical as it was formerly called, exchange rate for the U.S. Dollar was rock steady for many years at 20:1. “A Tical is a nickel” was a favorite saying.

"A 4th of July reception was held at the US Ambassador’s house and grounds for all Americans in town and foreign dignitaries, including the Russians with whom we were fully engaged in the Cold War"

Bank of America

The ‘farang’ community comprising many different nationalities and backgrounds was homogenous, cosmopolitan and growing rapidly. In the absence of today’s 5-star hotels and the multiplicity of restaurants, most entertaining occurred in homes. Homes were houses; no apartments had been built yet.

The ‘farang’ community comprising many different nationalities and backgrounds was homogenous, cosmopolitan and growing rapidly. In the absence of today’s 5-star hotels and the multiplicity of restaurants, most entertaining occurred in homes. Homes were houses; no apartments had been built yet.

Houses had decent-sized gardens for tea and garden parties. A house could be rented for US$100-250 per month. Home furnishings were mostly rattan and wicker couches and chairs with cotton-covered loose cushions. Dining tables and chairs were usually solid teak wood. Dinner parties at home were common and often elaborate affairs on good chinaware and crystal ware – very occasionally black tie with white dinner jackets or ‘Red Sea Rig’ – black tie, tux shirt, cummerbund but absent the jacket – in deference to the heat of the evening. It was all very civilized.

he food was still prepared on charcoal fire stoves in the outside kitchen – no gas or electric stoves then. Naturally, this took a small army of servants to cope and accommodate – a cook and/or No. 1, a food server, wash amah, coolie, gardener(s), gate guard (who mostly slept), and a driver for those with cars. Combined, they cost perhaps US$200-250 per month plus a 100-kilo bag of rice for everyone.

“Do you really need so many servants?” a young cousin of my family visiting from the U.S. asked rather incredulously. To which my father, chewing on his ever-present cigar, replied, tongue in cheek but with a straight face after counting on his fingers the number of domestic staff in his household, “Well, how can anyone get along with any fewer?”

The Thai elite loved grand balls with live orchestras (of varying composition and quality), most often held outdoors at the Suan Amphorn Gardens off the Royal Plaza and at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club. Foreigners were often in attendance, sometimes in droves. Everyone dressed for the occasion, thanks to Bangkok’s many dressmakers, tailors and shoemakers. There were no social barriers between the Thais and the farangs. It was all a bit exaggerated but that was an age of excess in absence of other entertainment diversions.

These functions were always well attended and lasted into the wee hours of the early morning. They were laughing, happy affairs where scotch, gin, vodka, Mekong and beer flowed freely and were consumed in copious quantities. A couple of hours of sleep and off to the office by 8:30 in the morning.

Few taxis to speak of were available so one got around by your own car or bicycle, bell-clanging trolley/trams, or on the smoke-belching buses – there were 27 independent bus companies in the city with overlapping but not interconnecting routes – or Vespa motor scooters or samlors, the bicycle type, not the motorized ones, and tuk-tuks were not yet invented.

Bangkok’s traffic has always been the subject of complaints and consternation. Then as now. The city was just somewhat smaller in those days.

Motor cars were not too numerous, as all had to be imported, but plenty were available for purchase. We owned a number of used cars in succession: a Peugeot 402, several Citroens 11BL, a Desoto, a Dodge, a Humber Hawk and finally a 1963 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. The biggest car in town, outside of the Royal stables, was the American Ambassador’s Checker – like the New York taxicabs of the day, big, heavy and strong (his was black, not yellow, and minus the ‘taxi’ sign)

To get away from the “hustle and bustle” of Bangkok, one went “upcountry” to Bang Saen, Siracha, Hua Hin or Chiang Mai. Average driving time to each in 1956 was 3 hours, 3 hours, 5-6 hours and perhaps a week, respectively. The trains north and south were faster. Your car needed new shock absorbers after each trip. Pattaya was just emerging as a seaside resort and Phuket was a Malacca Straits mining town.

Thailand was not really a tourist destination yet. In 1956, the city claimed only about 800 or so hotel rooms of so-called international standard. Having seen some of the facilities, I venture that that number was a generous overestimate. Overseas travel by plane meant an hour or so drive alongside rice fields and klongs on a two-lane tree-lined road to Don Muang Airport, 11 miles away, which had just recently been upgraded to have concrete runways and aprons and a proper two-story airport terminal building.

DC 2s, 3s, 4s and 6s were being flown as well as the triple-tailed Lockheed Constellations (‘Connies). Boeing 707s, DC 8s and Convair jets were still three years away from being flown commercially transpacific by Pan Am and TWA.23 By propeller planes, a flight from Bangkok to the U.S. West Coast could take three days with intermediate stopovers in Manila or Hong Kong, Guam or Wake Island, Honolulu and then San Francisco or Los Angeles.

To Europe – two days with overnights in Athens or Rome. Some commercial planes would not or could not fly at night. That summer of 1956, I returned from university having completed my Sophomore year and was a 19-year-old NROTC Midshipman 3rd Classman. To get back to Bangkok, I bummed rides on US Navy FLOG Wing air transports via Hawaii and the Philippines.

he food was still prepared on charcoal fire stoves in the outside kitchen – no gas or electric stoves then. Naturally, this took a small army of servants to cope and accommodate – a cook and/or No. 1, a food server, wash amah, coolie, gardener(s), gate guard (who mostly slept), and a driver for those with cars. Combined, they cost perhaps US$200-250 per month plus a 100-kilo bag of rice for everyone.

“Do you really need so many servants?” a young cousin of my family visiting from the U.S. asked rather incredulously. To which my father, chewing on his ever-present cigar, replied, tongue in cheek but with a straight face after counting on his fingers the number of domestic staff in his household, “Well, how can anyone get along with any fewer?”

The Thai elite loved grand balls with live orchestras (of varying composition and quality), most often held outdoors at the Suan Amphorn Gardens off the Royal Plaza and at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club. Foreigners were often in attendance, sometimes in droves. Everyone dressed for the occasion, thanks to Bangkok’s many dressmakers, tailors and shoemakers. There were no social barriers between the Thais and the farangs. It was all a bit exaggerated but that was an age of excess in absence of other entertainment diversions.

These functions were always well attended and lasted into the wee hours of the early morning. They were laughing, happy affairs where scotch, gin, vodka, Mekong and beer flowed freely and were consumed in copious quantities. A couple of hours of sleep and off to the office by 8:30 in the morning.

Few taxis to speak of were available so one got around by your own car or bicycle, bell-clanging trolley/trams, or on the smoke-belching buses – there were 27 independent bus companies in the city with overlapping but not interconnecting routes – or Vespa motor scooters or samlors, the bicycle type, not the motorized ones, and tuk-tuks were not yet invented.

Bangkok’s traffic has always been the subject of complaints and consternation. Then as now. The city was just somewhat smaller in those days.

Motor cars were not too numerous, as all had to be imported, but plenty were available for purchase. We owned a number of used cars in succession: a Peugeot 402, several Citroens 11BL, a Desoto, a Dodge, a Humber Hawk and finally a 1963 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. The biggest car in town, outside of the Royal stables, was the American Ambassador’s Checker – like the New York taxicabs of the day, big, heavy and strong (his was black, not yellow, and minus the ‘taxi’ sign)

To get away from the “hustle and bustle” of Bangkok, one went “upcountry” to Bang Saen, Siracha, Hua Hin or Chiang Mai. Average driving time to each in 1956 was 3 hours, 3 hours, 5-6 hours and perhaps a week, respectively. The trains north and south were faster. Your car needed new shock absorbers after each trip. Pattaya was just emerging as a seaside resort and Phuket was a Malacca Straits mining town.

Thailand was not really a tourist destination yet. In 1956, the city claimed only about 800 or so hotel rooms of so-called international standard. Having seen some of the facilities, I venture that that number was a generous overestimate. Overseas travel by plane meant an hour or so drive alongside rice fields and klongs on a two-lane tree-lined road to Don Muang Airport, 11 miles away, which had just recently been upgraded to have concrete runways and aprons and a proper two-story airport terminal building.

DC 2s, 3s, 4s and 6s were being flown as well as the triple-tailed Lockheed Constellations (‘Connies). Boeing 707s, DC 8s and Convair jets were still three years away from being flown commercially transpacific by Pan Am and TWA.23 By propeller planes, a flight from Bangkok to the U.S. West Coast could take three days with intermediate stopovers in Manila or Hong Kong, Guam or Wake Island, Honolulu and then San Francisco or Los Angeles.

To Europe – two days with overnights in Athens or Rome. Some commercial planes would not or could not fly at night. That summer of 1956, I returned from university having completed my Sophomore year and was a 19-year-old NROTC Midshipman 3rd Classman. To get back to Bangkok, I bummed rides on US Navy FLOG Wing air transports via Hawaii and the Philippines.

A 4th of July reception was held at the US Ambassador’s house and grounds, still on Wireless Road, for all Americans in town and foreign dignitaries, including the Russians with whom we were fully engaged in the Cold War. After the party, I joined a couple of other guys and went dancing with hostesses at the nightclub atop the Hoi Ten Lao restaurant, nine stories up in Chinatown – then the highest skyscraper in town.

The white dress uniform with brass buttons was quite an attraction to the lovely Thai ladies of the evening, and vice versa. A memorable night it was.

The 4th of July celebrated with a picnic was started in 1950 by the American Ambassador, a tradition still followed today.

From then until 1975, only three more tall buildings were built – the 10-story Tower Wing of the Oriental Hotel, the Dusit Thani Hotel at Saladaeng and the Chokchai Building on Sukhumvit Road. Thereafter, they sprang up like weeds.

I mentioned the Russians as the only place to mingle with them was at such diplomatic events or at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club, their only outlet to the social whirl of Bangkok. There, we played volleyball with them, we all being in our bathing suits – and they were very serious about the sport, as they were about almost everything else. They rarely lost. They had to report all of their contacts with Americans to their superiors and so did those of the US official community, including me as a visiting Midshipman.

The white dress uniform with brass buttons was quite an attraction to the lovely Thai ladies of the evening, and vice versa. A memorable night it was.

The 4th of July celebrated with a picnic was started in 1950 by the American Ambassador, a tradition still followed today.

From then until 1975, only three more tall buildings were built – the 10-story Tower Wing of the Oriental Hotel, the Dusit Thani Hotel at Saladaeng and the Chokchai Building on Sukhumvit Road. Thereafter, they sprang up like weeds.

I mentioned the Russians as the only place to mingle with them was at such diplomatic events or at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club, their only outlet to the social whirl of Bangkok. There, we played volleyball with them, we all being in our bathing suits – and they were very serious about the sport, as they were about almost everything else. They rarely lost. They had to report all of their contacts with Americans to their superiors and so did those of the US official community, including me as a visiting Midshipman.

"Massage parlors, bath houses and short-time/curtain hotels were unknown in 1956 – they awaited the Vietnam War years. However, despite public protestations to the contrary, for several centuries in the provinces as well as in the Green Light areas of the capital, brothels and tea houses abounded"

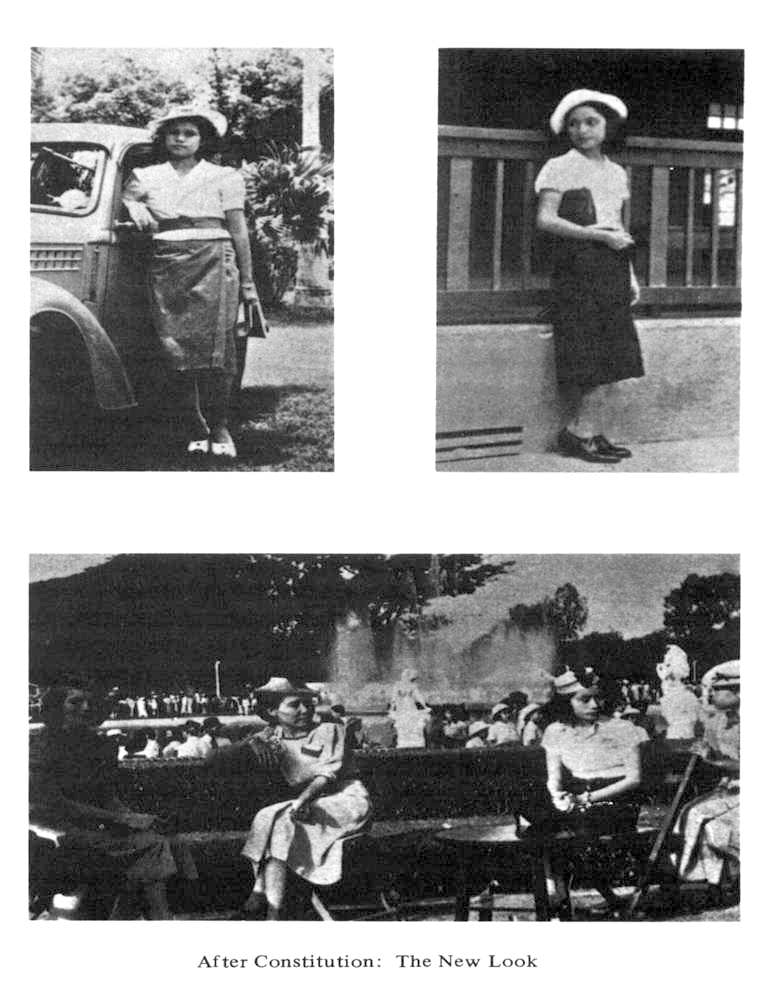

Farangs were still wearing white linen or sharkskin (actually quite a smooth textured fabric) cotton suits in those days. In the absence of air-conditioning, they were much cooler than colored clothes. The ladies wore cotton dresses, except for evenings out when gowns and Thai silk were more the order of the day. Jeans were not socially acceptable. Thai women, then as now, were always elegantly attired, coiffed and bejeweled.

Benny Goodman and his big band toured Asia, courtesy of the State Department cultural programs, and in late 1956 played for two weeks in Lumpini Park at the U.S. exhibit at the Constitution Fair in Bangkok. The highlight was playing for and with H.M. the King, a very accomplished musician in his own right even then. Opium dens were still legal in 1956 and in some households, more often than not Chinese, smoking opium pipes after dinner was the equivalent of the British custom of after-dinner cigars and port/brandy.

Benny Goodman and his big band toured Asia, courtesy of the State Department cultural programs, and in late 1956 played for two weeks in Lumpini Park at the U.S. exhibit at the Constitution Fair in Bangkok. The highlight was playing for and with H.M. the King, a very accomplished musician in his own right even then. Opium dens were still legal in 1956 and in some households, more often than not Chinese, smoking opium pipes after dinner was the equivalent of the British custom of after-dinner cigars and port/brandy.

To my father, the opium dens, being quiet, dark and sedate places, were tourist attractions for visitors to see, as was Thai boxing in one of the two stadiums of the day, and horse-racing at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club on weekends.

Down in the area just outside the Port of Bangkok at Klong Toey and catering to the merchant seamen and crews of an occasional visiting man-o-war, were the Mosquito Bar and the Venus Room. Introduced to me by my father, they were home to the roughest toughest set of Thai hostesses as I have ever encountered. If there were not at least two brawls a night, involving the patrons too, it was considered a dull evening.

Down in the area just outside the Port of Bangkok at Klong Toey and catering to the merchant seamen and crews of an occasional visiting man-o-war, were the Mosquito Bar and the Venus Room. Introduced to me by my father, they were home to the roughest toughest set of Thai hostesses as I have ever encountered. If there were not at least two brawls a night, involving the patrons too, it was considered a dull evening.

Uptown, in addition to the likes of The Cathay Cabaret, Hoi Tien Lao and Chom Suey Hong, were the Silver Palm (owned by Jorges Orgibet along with Alexander McDonald and Willis H. Bird), Moulin Rouge, Sani Chateâu, Salathai Club, Starlight Club, Café de Paris, International Club and the Lido cabarets as well as the venerable Bamboo Bar of the Oriental Hotel for prowling by the more sophisticated salubrious types, or as our British friends would say, “the upper classes”.

Whatever, Bangkok's nightlife was wide open, affordable and accommodating to all tastes and pocketbooks. I should add that massage parlors, bath houses and short-time/curtain hotels were unknown in 1956 – they awaited the Vietnam War years. However, despite public protestations to the contrary, for several centuries in the provinces as well as in the Green Light areas of the capital, brothels and tea houses abounded and there was no lack of cabarets and dance halls and girls to go with them

Whatever, Bangkok's nightlife was wide open, affordable and accommodating to all tastes and pocketbooks. I should add that massage parlors, bath houses and short-time/curtain hotels were unknown in 1956 – they awaited the Vietnam War years. However, despite public protestations to the contrary, for several centuries in the provinces as well as in the Green Light areas of the capital, brothels and tea houses abounded and there was no lack of cabarets and dance halls and girls to go with them

RSS Feed

RSS Feed